“I promise, I’ll come back for you. I promise, I’ll never leave you.”

I was late to the party for The English Patient, Anthony Minghella’s Academy Award winning Best Picture from 1996. Having watched the March 24, 1997 Oscars telecast, I was then-clinging to an ill-fit graduate school program, and I had just found full-time work. Mildly depressed, I was watching low hanging fruit like Scream (Wes Craven, 1996) and Private Parts (Betty Thomas, 1997) rather than risk more thoughtful fair like Crash (David Cronenberg, 1996) or The People vs. Larry Flynt (Milos Forman, 1997).

When I finally saw The English Patient, knowing it had bested fan favorites like Fargo (Joel Coen, 1996) and Jerry Maguire (Cameron Crowe, 1996) for pic of the year, I was prepared for something really terrific. What I got, instead, was a tour de force in epic-scale, craft excellence that clings to a love story I didn’t accept.

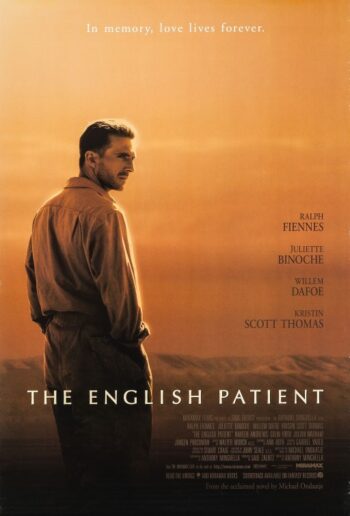

The setup is simple: in 1945 Count László de Almásy (Ralph Fiennes), a Hungarian explorer and mapmaker, is burned badly in a plane crash. While being comforted until his death, László entertains his French-Canadian nurse, Hana (Juliette Binoche), with the story of his tragic love affair with Katharine Clifton (Kristin Scott Thomas), a married British woman.

The backdrop is World War II. Germans are on the march, subterfuge and spying is rampant, and maps to North Africa seem pivotal to concluding the war. We move from the mid-1930s through 1945-ish, and through multiple countries (Italy, Libya, and Egypt) before we settle on the crux of the movie: László and Katherine are beautiful Europeans worth their weight in gold as advertisements for good fashion and breeding, but they are adulterers and my moral training tells me cheaters shouldn’t be happy, no matter how photogenic they may be.

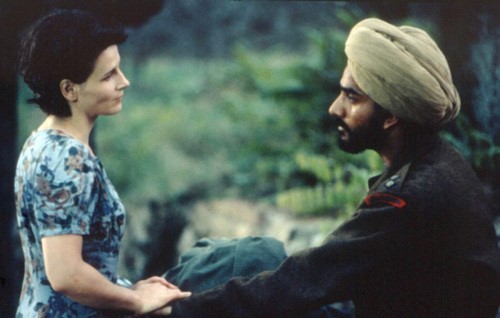

Hana’s story is set in the movie’s present. Trying to heal the hole in her heart from tending so many injured and dying people, into her midst steps a British-Sikh bomb specialist, Kip (Naveen Andrews). There is instant chemistry between them, built from careful glances and thoughtful silences, not just the requirements of a narrative that hinges on a Herodotus-reading Hungarian and an adulterous Brit. Hana and Kip’s blooming romance is where the movie finds fire, although at the margins of the László/Katherine pity party, and that doubling in the narrative, an A-story with its B-story echo, is wrongly organized.

Sure, we watch László and Katherine make love, and we see them in moments of candid, nude intimacy. Yes, we see Katherine’s suffering as she realizes the toll of her affair on her husband, Geoffrey (Colin Firth). And we visit places in North Africa most of us will never see, often from the height of an elegant biplane. Also, Gabriel Yared’s score is top notch.

Sorting through narrative complexities without linear progression, we also meet Willem Dafoe’s Caravaggio who wants to avenge himself on László because László took action to save Katherine that had much collateral damage. Working through an experimental story, enjoying lush production design, and seeing the war through an unusual angle are all strong suits built on expert craft. But the movie’s greatest thrill is in watching Hana help Kip wash his hair.

–December 31, 2018