“Go hence and have more talk of these sad things.”

High schoolers are often death marched through William Shakespeare’s “Romeo and Juliet.” For some, the takeaway is that Shakespeare sucks; for others, the main idea is that young love can be painfully beautiful.

One reason why “Romeo and Juliet” tantalizes audiences is its ready-made story of woe that centers on two warring families, the Montagues and Capulets, who live in the divided city of Verona. The Montagues have one child, a son, Romeo, and the Capulets have one daughter, Juliet. The pair meet, fall in love, marry, and eventually die, each in a colossal misunderstanding: Romeo believes Juliet has committed suicide, although it’s merely a trick, and he kills himself, whereupon she finds him dead and kills herself.

Over the years many teens have labored to unspool lines of iambic pentameter from the play in order to figure out what’s happening. Much resonance has also been felt among those that see themselves as young lovers in the first blush of intimacy, which lends an easy comparison to the wonderful, terrible example of Romeo and Juliet.

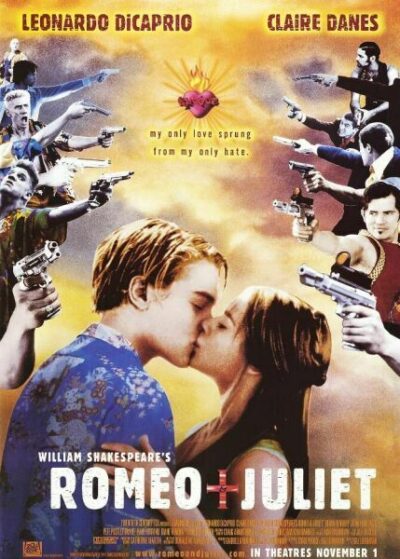

Australian filmmaker Baz Luhrmann adapted Shakespeare’s play with Craig Pearce, and the result, William Shakespeare’s Romeo + Juliet, was released in 1996. It stars Leonardo DiCaprio as Romeo and Claire Danes as Juliet, and the backdrop is a contemporary city where the two families are now also corporate entities. The Montagues are mostly white, and the Capulets are multi-ethnic; there is an agonized police chief, a wily governor’s son, a concerned Catholic priest, and several notable pop songs of the era, including “#1 Crush” by Garbage, “Kissing You” by Des’ree, and “Talk Show Host” by Radiohead. Swords have been exchanged for pistols, cars and helicopters appear instead of horses and carriages, and the chorus-like value of TV news broadcasters stitch together the story at appropriate breaks in the plot.

To see Romeo + Juliet today is disappointment tripled. Firstly, Luhrmann’s movie lurches through the excesses of his peculiar kind of movie craft (showy camera movement, altered speeds of film stock, extravagant costumes, and general formal manipulation that seems depthless). Second, the script uses the Bard’s poetry, largely as written, through a then-“hip” cast that includes luminaries (Miriam Margolyes and Pete Postlethwaite), miscast but game performers (Paul Sorvino and M. Emmet Walsh), and scene stealers (Vondie Curtis-Hall and John Leguizamo). Third, who really cares about this R+J? Sure, DiCaprio and Danes are gorgeous, but the energy of the movie lies elsewhere.

In particular the movie’s note of genius is Harold Perrineau as Romeo’s best friend Mercutio. He is Black while DiCaprio is White; he’s Queer-ish, bending gender and sexuality norms while everyone else goes to war in defense of a basic breeder coupling in R+J; he’s magnetic, pained, and attractive while most everyone else is either off-the-rails bonkers (see anything featuring the senior Montagues or Capulets) or glossy and superficial as a magazine advertisement (see DiCaprio and Danes, over and over and over).

Should you see William Shakespeare’s Romeo + Juliet?

If you’re a Shakespeare completist, yes. Otherwise, look for a different take on the story. Perhaps the Franco Zeffirelli “straight” version, called Romeo and Juliet, from 1968? Or, apply the underlying lesson of R+J, which is that young people sometimes purposefully violate social norms, as in miscegenation, in which case go see Sanaa Lathan’s Something New (2006) where the lovers don’t have to die. Or, consider the year when Luhrmann brought his adaptation to life, and turn to another, better, more memorable, no less tragic semi-adaptation by Lars von Trier in his rather bleak story of perfectly mismatched lovers, Breaking the Waves (1996).

–October 31, 2018