“FUBAR.”

War is a difficult subject to portray in a movie. If the aim is a celebration of violence, then the response is uncomplicated moral clarity. If the aim is an exploration of the complexities and destructiveness of the wartime experience, then the response is often far more ambiguous, troublesome, and confused. When these two aims collide in a big-budget Hollywood vehicle, helmed by one of the leading lights of cinema history, the result is a mix of heartfelt jingoism and bone-crunching verisimilitude.

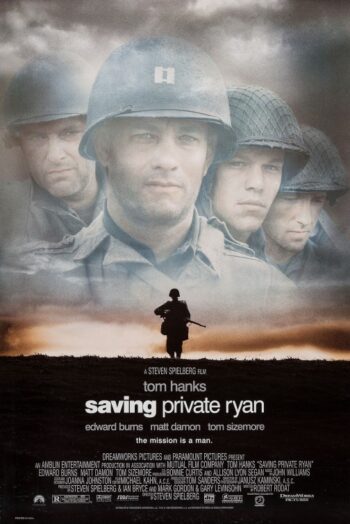

Steven Spielberg’s 1998 master clinic in film making, Saving Private Ryan, offers two distinctive views of history: clinical re-enactment of battle, from the level of a common trooper, and sentimental characterization of teamwork that celebrates self-sacrifice and honor. The movie’s story depends on a tragic detail of war: that a group of adult children from a single family might be killed in a single incident, thereby wiping out that family line forever. Precedents for this scourge are many, but the most notable record may be the deaths of the five Sullivan brothers—George, Frank, Joe, Matt, and Al—who died, en masse, when their naval cruiser, the U.S.S. Juneau, was struck by a Japanese torpedo in 1942.

In Saving Private Ryan this mass death premise is adjusted to focus on the four Ryan brothers who have all enlisted to fight in World War II. During the administrative aftermath of D-Day, a cleric in the War Department realizes that three of the Ryan boys have been killed, and that the fourth, Private James Ryan (Matt Damon), a paratrooper, is lost behind enemy lines in coastal France. A squad of hard-fighting Army men, all survivors of D-Day, are re-assigned by the Secretary of War to recover the lone Ryan boy and return him safely home. Through arduous circumstances, experiencing much difficulty, the squad saves Ryan, although six of eight men die in the process.

This snap summary is totally correct. But the magic of this movie is its appeal to emotional reality through the technical means of filmmaking that deliver a you-are-there feeling.

When I first saw this movie in the summer of 1998, I had a habit of smuggling into the theater eight Hershey Kisses. My usual pattern was to unwrap each Kiss during the previews and only begin eating them when my feature presentation began. Depending on my mood, I would chew up my treats or suck on them slowly, but it was a rare movie in which I still had chocolate to enjoy after the first 10 minutes of the feature was over.

In Saving Private Ryan I consumed just one Kiss during the moody prologue. Then I prepared to eat the second of my eight treats when the D-Day landing unspooled. I ate nothing more for the next 20 minutes, feeling overwhelmed by the violence, the mood of futility, and the disgusting prospects of mutilation afforded by all manner of projectiles and munitions.

For me, this pause in my habit was significant. While I did eventually eat my candy, I was pulled fully into the vignettes and set pieces that form the core spectacle of Saving Private Ryan. And, like the fighting men on-screen, and like the fighting men and women in real life, I was equally treated to the off-time conversations and bonding that accumulate around people forced to perform difficult tasks together and in close quarters.

Saving Private Ryan is not war porn made to encourage saber rattling; it is a respectful, occasionally sentimental, effort to re-organize our historical memory of World War II. It has a cast of hundreds, headlined by Tom Hanks, Tom Sizemore, Barry Pepper, Giovanni Ribisi, Vin Diesel, Edward Burns, Adam Goldberg, and Jeremy Davies, and it is meant to be the cinematic tour de force that it is.

All praises to this fine, fine cast, but the real brilliance of the movie is in its technical achievements. Michael Kahn, the editor, ably creates anxiety in battle scenes, stillness in peaceful moments, and moves the energy of the story through its three-act structure, all while maintaining perfect clarity of activity and motive in sequences that include thousands of moving parts. Which requires the images that Janusz Kamiński and his crew captured while on European location, both outdoors, mostly, and in doors, seeking the best way to re-create the times of the 1940s by manipulating the image, particularly through desaturation techniques and by modifying the way lights enters the camera. Then we acknowledge the lead figures in the sound recording and mix, Gary Rydstrom, Gary Summers, Andy Nelson, Ron Judkins, and Richard Hymns, who manage to make the audio track of the movie into a stereophonic experience that involves three-dimensions of gunfights, conversation, and rain.

Saving Private Ryan has become a mainstay of Veterans Day and Memorial Day TV programming, and it is in the National Film Registry as one of the great works of American cinema that should be preserved forever. It is also a difficult story with incredibly realistic acts of violence that will make a person shudder and wince, most of all when that violence is connected with the very appealing faces and bodies of the cast that bear the brunt of this violence as an everyday part of their duty to the armed service of their country.

–October 31, 2018