“You cannot love words. You can’t be in love with a word. You can only love another human being. That’s perfection.”

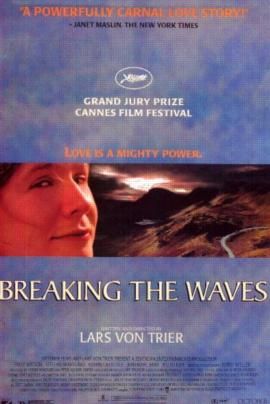

Because high schoolers often read and dislike William Shakespeare’s “Romeo and Juliet,” thoughtful teachers seek contemporary tie-ins to enliven an old story of young love gone wrong. In 1996, Baz Luhrmann’s William Shakespeare’s Romeo +Juliet fit the bill with an update of the the Bard. For my money, though, the best adaptation of “Romeo and Juliet” from 1996 is Lars von Trier’s Breaking the Waves.

Having debuted at the Cannes Film Festival where it earned the Grand Prix, Breaking the Waves is set in the 1970s in Scotland. The story opens with the wedding of Bess McNeil (Emily Watson) and Jan Nyman (Stellan Skarsgård). She’s been raised in a strict Calvinist church and has a history of mental illness; he’s an outsider and an atheist who works on an oceanic oil rig. Her community disapproves of the union, but they marry anyway, and their life is complicated by her on-going talks with God, in which she voices both halves of the conversation, and his absence when working. One day he’s injured on the job and paralyzed, and they must learn how to adjust. His solution is for her to begin seducing men to enjoy her body and report to him what she’s done so he can share in her carnal journey. Her friends and family learn what’s going on, and she’s threatened with institutionalization as Jan deteriorates. Desperate, Bess talks with God one final time and decides she must sacrifice herself to save her husband, which she does by giving herself to a group of brutal sailors who gang rape her. Jan recovers from his injuries and buries Bess at sea under the sight and sound of heavenly church bells ringing out in the sky.

To this summary must be added the fact that Breaking the Waves is a very melancholy experience, and it stays in the imagination as a story of young love gone wrong but also as a study of faith combined with devotion to produce an odd kind of grace. It’s totally unconventional, filled as it is with several key techniques von Trier championed as a leading light in the Dogme 95 movement, which includes mostly location shooting, natural sound recording, and vertiginous handheld camerawork. Breaking the Waves is further divided into seven chapters and an epilogue, each divider consisting of a single panorama shot accompanied by period music of the era like “Life on Mars” by David Bowie and “All the Way from Memphis” by Mott the Hoople.

For those uninitiated in European art cinema, Breaking the Waves is tough stuff. It includes full frontal male and female nudity, explicit sexual intimacy, long takes of characters in contemplation, and performers, especially Emily Watson, who fearlessly attack a premise that is so far from the norms of Hollywood that it beggars the imagination. This is a movie experience based in duration, suffering, and sudden confrontation with unforeseen themes that have always been present but are nonetheless surprising.

Re-enter “Romeo and Juliet.”

Instead of the Montagues and Capulets, we have the Calvinists and atheists. Romeo is Jan; Juliet is Bess, obviously. The impossible connection between them is now expressed as a study of village life being assailed by modernity in the form of faithless energy extractors, and the varied characters that make up the Shakespearean source are here present: Friar Laurence is the judgmental Priest (Jonathan Hackett), Count Paris is the friendly but desirous Dr. Richardson (Adrian Rawlins), Nurse is Bess’s widowed sister-in-law and voice of conscience Dodo McNeil (Katrin Cartlidge), and the various townsfolk and rig workers fill-in the supporting parts of Verona, now envisioned as coastal Scotland.

This is not to say that Breaking the Waves ends in utter tragedy, as in the source; we see how Bess’s faith and living energy is transferred into her husband, allowing this new-fangled Romeo to survive. But we also confront the difficult, enviable fact of Watson’s brilliant performance, which transforms our understanding of a possibly-crazy country girl-turned-plaything for an egomaniac into the vivid story of God’s presence in the most desperate circumstances.

Romeo and Juliet lost everything because of family obligation and tragic misunderstanding at the climax of their story. In Breaking the Waves, Romeo unconventionally loves his Juliet, and she purposefully defies all family obligations to give her Romeo everything, including the gift of her life for which the heavens ring in an absurdly beautiful final image as church bells dangle in the clouds.

–November 30, 2018