“A pessimist thinks things can’t be worse. An optimist knows they can.”

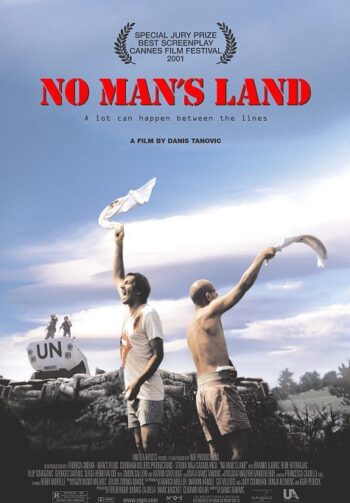

Danis Tanović’s No Man’s Land (2001) is a real bummer. It is also a thoughtful consideration of why and how conflict rises among like-seeming people, and how that conflict threatens certain basic beliefs many of us hold in common, as in the pursuit of self-interest versus the power of cooperation, which brings to mind a philosophical bird walk.

By definition, cynicism is, “an inclination to believe that people are motivated purely by self-interest.” The cynic, therefore, looks for the down side of things to prepare for when things go wrong. This tendency is clearly on Tanović’s mind throughout No Man’s Land.

The opposite of cynicism is harder to pin down. Still, optimism comes to mind with its ideal disposition that sees possibility in disappointment, yet trust is a likelier flip side, defined as, “the state of being responsible for someone or something.” Trust is a relational experience that requires outside support inside a community rather than maintaining a lonely separation from other, which is another idea clear at play in No Man’s Land.

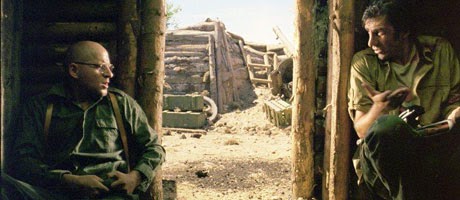

The setting for the movie is the Bosnian War (1992-1995), and the story concerns three rival soldiers trapped between front lines with no way to safely return “home” because one of them has been booby-trapped by a landmine that will kill them all if he moves. Our Bosnian Muslim is Čiki, played by Branko Đurić, and his land-mined confederate is Cera (Filip Šovagović). Both men are new to the front and dressed as civilians. Opposite them is a uniformed Bosnian Serb, Nino, (Rene Bitorajac), who is also a rookie soldier. When the UN Protection Force is called in to help, a truce is declared to extricate the three soldiers, but then everything goes wrong. Čiki and Nino kill each other, and Cera is left in the trench as the UN commander leaks false intelligence, hoping the belligerents will attack the trench, set off Cera’s landmine, and erase evidence of the day’s struggle.

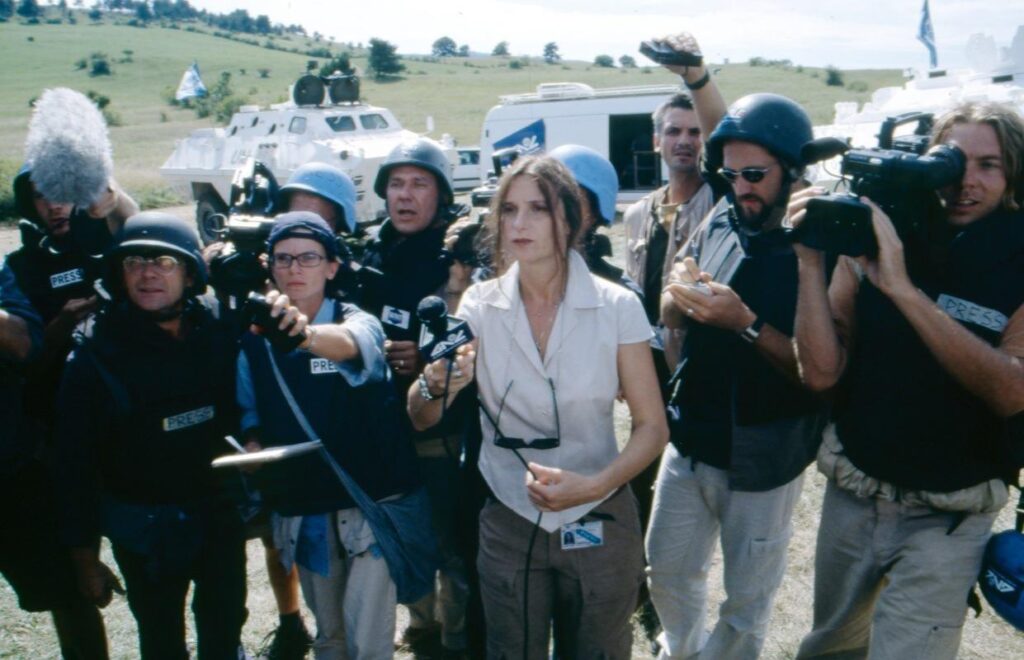

After tenuously presenting several forms of trust, between a French UN peacekeeper and a go-getter British journalist, or between a German bomb specialist and Cera, as two examples, this war story ends in futility. Tanović’s script tells us that self-interest leads to death, that trusting in the goodness of others will be undermined by saving face (another kind of self-interest), and that all we can hope for is a peaceful death, which we will never achieve since we are, every last one of us, participant-witnesses in this dark journey of life.

By presenting such a cynical move to cover up the inadequacy of peace-keeping abilities among peacekeepers, No Man’s Land shifts from being a description of the gap between opposing troops and into an existential statement. War is hell, as the adage goes, but it’s also lonely and sad.

–January 31, 2019