“When I had a problem, my mom and dad would tell me to look at it another way.”

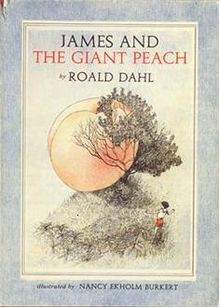

When Roald Dahl published James and the Giant Peach in 1961, he was a Welshman in his middle 40s, married to the American actress Patricia Neal, and the father of three (they would eventually have five children together). He was a few years away from being celebrated for his best-known novel, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, which came out in 1964, and he was well on his way to leveraging his unusual background for literary fame and fortune.

Packed into the first four decades of his life Dahl suffered a series of tragedies. His sister and father died while he was a child, and he was suffered various unpleasant school experiences, including corporal punishment, as a middling scholar of no discernible gifts. Finally delivered into adulthood he worked for Shell Oil and travelled throughout Africa until World War II began. He became a Royal Air Force pilot, a diplomat, and a government intelligence officer before his ultimate career as a writer took root. Working with Walt Disney Productions, for whom Dahl had written the youth-targeted novel The Gremlins in 1943, his success among adult readers was nil, following the poor reception of Some Time Never: A Fable for Supermen in 1948. By fine-tuning his talents to fit the wants and needs of then-emerging juvenile readers, Dahl began to more openly express his fascination with animals and misanthropic behavior.

James and the Giant Peach tells the story of an orphaned boy who lives with his two terrible aunts. One day magic enters his life in the form of a giant peach, inside which live sentient, giant-sized insects who become James’s surrogate family to help him escape his aunties and move to America where his dreams become reality. The novel is filled with poetry and fantasy elements that clash mightily with real world physics (moving the peach from the UK to the USA involves tethering seagulls), and it’s everywhere apparent that Dahl sides with the boy, James, upon whom the insects dote as a mascot-turned-savior because he has common sense while no other creature seems to at all.

BBC One staged a TV version of the novel in 1976, but a theatrical adaptation for the movies didn’t come together until 1996, after much wrangling with Dahl’s estate (he died in 1990). The effort was completed by Walt Disney Pictures, eager to find a new branding handle during the second golden age of big screen animation, which was well under way after the incredible success of The Lion King (Roger Allers and Rob Minkoff, 1994), under the leadership of entertainment titan Michael Eisner.

Disney animation alum Tim Burton co-produced the movie and lent the project his imprimatur, yielding responsibility for directing the movie to Henry Selick, a stop motion animator who had risen to acclaim, also under Burton’s influence, with the cult hit The Nightmare Before Christmas (Henry Selick, 1993). A bevy of attractive vocal performers was hired, including Simon Callow, Richard Dreyfuss, Jane Leeves, and Susan Sarandon, and the whole affair was pinned to the appeal of a debut performer, Paul Terry, who was 10 years old.

The problem with Selick’s James is that it’s formed in two parts that don’t fully cohere. The live action prologue and epilogue of James’s terrible life with his terrible aunties, played broadly and with gross facial make-up by Joanna Lumley and Miriam Margolyes, is flat and without emotional impact despite the fact that James is plainly abused, emotionally and physically. On the other hand, the stop-motion animation features big, big bugs that sing and devolve into ethnic stereotype (Sarandon’s spider is an Eastern European vamp who would be comfortable in Silent movies), which is lively but hamstrung by the limitations of Dahl’s book.

It’s really hard to care for James and his preferred family, all of whom appear simply to explain or amplify his innocent need to find a sense of home; no person or creature on-screen is fully realized, save for the aunties who at least have appetites that make them earthy and true, despite their despicable selfishness and greed. James is always saintly and pure, kindly and open-hearted, and there is no real stake to worry over because the journey that he goes through segues quickly from artificial-seeming live action and into a lengthy middle of voice over accompaniment to stop motion fantasy that exists primarily to sell the songs of Randy Newman and resolve to “Happy Ever After.”

Younger viewers may look at James and the Giant Peach and enjoy the wish fulfillment of seeing strange creature like a centipede and earthworm come to life as comic foils. My guess is that most adults will look at the 79-minute running time and consider how long that really feels when it’s quite possible to read the whole book in very close to that length of time.

–December 31, 2018