“There are certain rules that one must abide by in order to successfully survive a horror movie.”

The Wes Craven horror movie Scream (1996) should be sub-titled “Suburban White kids are rich and have too much time on their hands, so they drink and party and die.”

The story takes shape around the discovery of a gruesome double murder that features a home invasion, many knife wounds, and disembowelment. Action shifts to the local high school where a virginal girl with a tragic past fends off the sexual advances of her handsome boyfriend only to become the target of a serial killer. As bodies pile up, red herrings appear until the good girl wins.

So far, so good. But Scream is actually about the conventions of slasher movies turned on end to nonetheless satisfy gross-out moviegoers looking for blood.

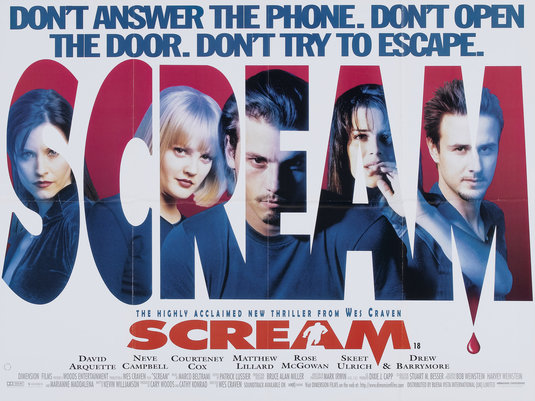

The star is Neve Campbell, playing Sidney Prescott, and her brooding boyfriend, Billy Loomis, is played by Skeet Ulrich. The rest of the cast includes then-emerging screen performers like David Arquette, Rose McGowan, Liev Schreiber, Jamie Kennedy, and Matthew Lillard, a faded child actress, Drew Barrymore, and two TV stars looking for big screen glory, Henry Winkler and Courtney Cox.

The fun of Scream, aside from its sequels and the spin-off parody films in the Scary Movie cycle, is the way audiences watch the action and see themselves acknowledged as an audience. In film studies we call this self-consciousness. When that kind of self-consciousness is enhanced through placing on-screen references to other movies that serve as the basis for what we see on-screen, we arrive at a cool French term, mise an abyme, or “placed into the abyss,” which means that an expressive work places a copy of itself somewhere inside it, and this mirroring is what makes the expressive work so exciting.

Think about it this way: Scream was written by Kevin Williamson, then of little repute but now known for writing the first four Scream movies, along with I Know What You Did Last Summer (Jim Gillespie, 1997), and creating the TV shows Dawson’s Creek (1998-2003) and The Vampire Diaries (2009-2017), among others. He’s a very plugged-in guy. His script liberally soaks Sidney’s world in the pabulum of horror movies, but then stirs the pot to arrive at something new.

The urtext is John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978) that we see playing on a TV in several scenes, and this movie-within-the-movie describes, simultaneously, what Scream re-enacts through gnarlier gore effects, a series of giant houses where mayhem hinges on the use of telephones and not knowing what’s just around the corner, and the attractive qualities of a fresh cast (Campbell et al.). Other movie references appear in the characters’ repartee, in the composition of scenes, and in the undeniably powerful imagery of suffering and pain that form the backbone of every slasher movie since Psycho (Alfred Hitchcock, 1960) and Peeping Tom (Michael Powell, 1960). While not for all tastes, Scream sees the renewal of a then-moribund category of movies that work, and work hard, to terrorize teenagers and young adults.

–October 31, 2018