“A film. A people. A legend.”

Imagine seeing and hearing these hot button items in a single movie: full-frontal male nudity, extramarital sex, polygamy, rape, animal and child abuse, murder, frequent urination, and walrus heart tartare. Then combine these subjects with a presentation of modern Canada’s ancient aboriginal people and let the whole thing run to nearly three hours in length.

It’s a lot to take in, and the story’s backstory concerns a malevolent shaman who overcomes the patriarch of a small human settlement, killing him and sewing evil into the world. Rivalries develop and old ties are sundered as the community absorbs the intrusion into an otherwise harmonious life at the edge of the natural world. Two generations later, through many trials, a hero emerges to banish the evil spirit and restore order under the watchful presence of communal elders.

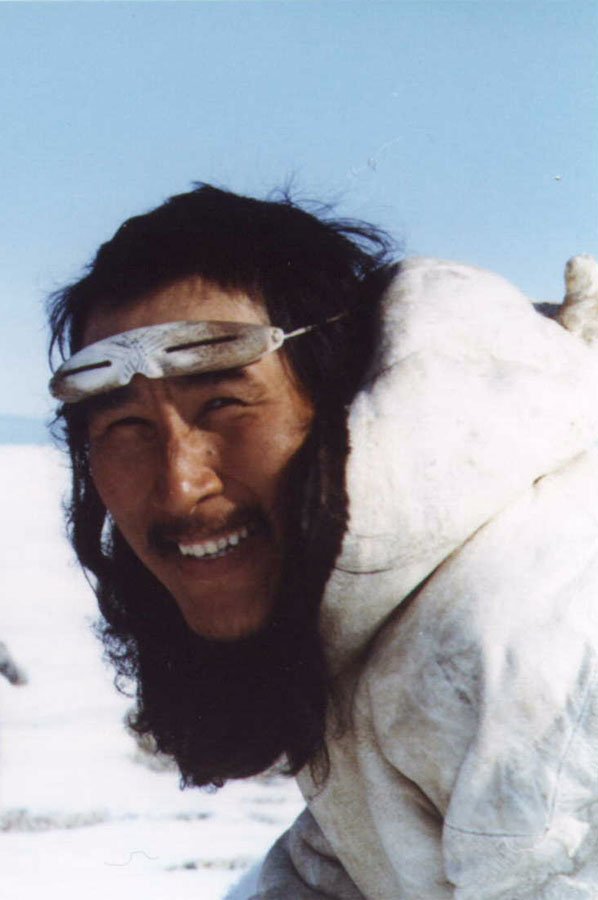

In a nutshell that’s the story of Zacharias Kunuk’s Inuit movie Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner (2001). Our hero, who offers us a lengthy sequence of full-frontal male nudity to demonstrate why he is called “The Fast Runner,” is the movie’s namesake, Atanarjuat (Natar Ungalaaq). His problems revolve around the romantic feelings he has for Atuat (Sylvia Ivalu), a young woman betrothed to Oki (Peter-Henry Arnatsiaq), community bully and prime repository for the malevolent shaman’s evil. Atanarjuat’s journey is further complicated, first by his deferential connection with his elder brother Amaqjuaq (Pakak Innuksuk), “The Strong One,” then by his eventual marriage to Atuat, and, finally, to his acceptance of a second wife, Puja (Lucy Tulugarjuk), who is Oki’s sister and another source of evil in the community. From these various ties develop acts of infidelity, murder, and rape, but the heart of the story is in watching how Atanarjuat learns to accept the advice of several elders to cast out the shaman’s evil spirit and ensure the future of his small clan.

To summarize Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner in this way, though, is limiting despite being true. The movie is more than another hero’s journey, which has been so well codified by the likes of Joseph Campbell, among others[1]. The fact is Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner is an ethnographic and technical marvel that marries magical realist impulses with unconventional narrative pacing. Its achievement is in willing-into-existence a story starring Inuit people who solve their problems without resorting to graphic violence. In fact, the one bit of narrative frustration isn’t that our hero fails to accomplish his goals (he does); the conventions that we believe should result in his victory, like outsmarting his rivals with a witty bon mot, is transformed into a ceremony of forgiveness, whereby Oki, Puja, and their supporters are peacefully banished from the community rather than being graphically and violently destroyed.

As a collaborative project of First Peoples, the movie was made by a cast and crew primarily made up of Inuit artists shooting with digital tools in the Arctic Circle. It manages to painstakingly re-construct a pre-modern lifestyle that’s rather close to the elements and lived almost utterly at the mercy of animal migration patterns where the world is very, very cold. Everyone wears animal skin—rabbit and seal, mostly—and everyone eats meat, almost exclusively—birds, seal, walrus, caribou, fish, and rabbit.

While we watch these people hunt, forage, and relax, Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner asks us to suspend our common disbelief at the presence of spirits that animate everyday behavior. We are required to accept, as the characters in this story world certainly do, that cycles of lightness and darkness, both as moral guidelines and as descriptions of seasonal weather, run through the patterns of our families and clans, all the way through the present.

It helps, immensely, that the movie drives through these lessons of place and pedigree by putting us on the ice and snow along with the characters we come to recognize as three-dimensional despite their unconventional lifestyle. Each character is miles from being movie star good looking with polished teeth and perfect skin; everyone has to cope with freezing snot; much of the action takes place through the conversation and activity of characters who spend their time hidden under layers of protective clothing.

In fact, whole sections of the movie are devoted to the quotidian rituals of survival. We participate in egg collection, seal skinning, igloo production, family meals and tent construction, sledding, dog husbandry, child care, communal play, worship, etc., and none of it is rushed or placed before us accidentally; everything on-screen matters to establish a tone, voice, and sense of place that supports the underlying folkloric adaptation of the story of Atanarjuat, who must overcome his rivals after suffering betrayal.

Finally, after all else we’ve endured alongside our hero, we see the restored promise of Igloolik, or “place of houses.” Evil is driven from the land, the challenge of the shaman’s curse is mastered, and Atanarjuat and Atuat look forward to raising their son. It’s a simple ending to a simple story that results in the safety of home.

–February 28, 2019

[1] See Edward Burnett Tylor, Carl Jung, and Erich Neumann, and a host of critics who think the whole idea of archetypes is bunk.