“Fire was a symbol of power and a means of survival. The tribe who possessed fire, possessed life.”

In the early 1980s there was an uptick in films focused on pre-historic humans. The sources of this fascination were several, but Stanley Kubrick’s 2,001: A Space Odyssey (1968) is surely part of the conversation since it contains “The Dawn of Man.” This opening segment features early hominids scratching out a fragile existence until they encounter a black monolith that lends them enhanced intelligence—just enough to fashion bludgeons cut into the film as associated links with the space race of the 1960s.

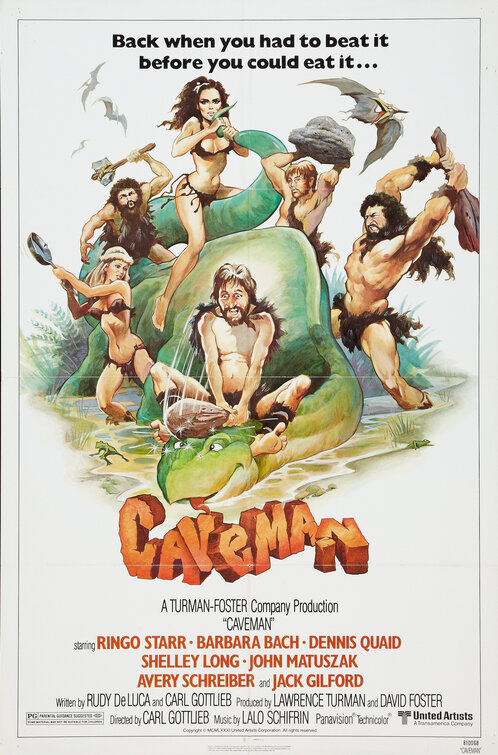

Mel Brooks entered the fray in the summer of 1981 with History of the World, Part I, another movie told in several segments, and it opens with a series of gags about and set in the Stone Age. But it was Carl Gottlieb’s springtime joke fest Caveman that got my attention and planted the idea of an early ’80s focus on pre-historic humans.

For my 8th birthday, my parents allowed me to bring several friends to the movies. Aside from standing in line for tickets, the only memory I have of that day was a rather exciting joke.

In one of the movie’s comic bits three cavemen consult with one another about animal excrement. The first says, “caca.” The second: “poo-poo.” The third: “shit.” We boys were crying with laughter, as my parents likely wondered how they should confess to the sin of profane exposure during eventual drop-offs that would tie-off the day.

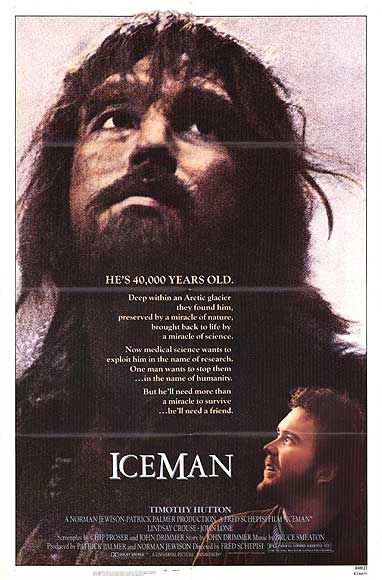

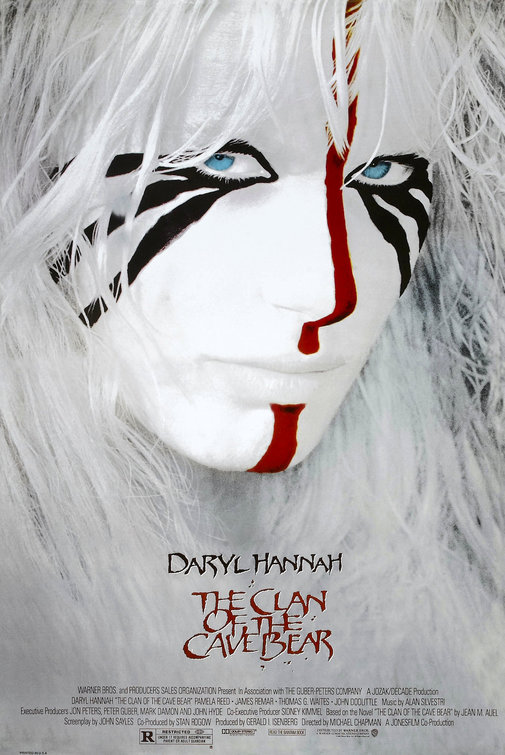

To my memory, the trend of pre-historic movies petered out with Iceman (Fred Schepisi, 1984), the story of a thawed caveman who encounters the modern world, and The Clan of the Cave Bear (Michael Chapman, 1986), derived from the much-respected novel by Jean M. Auel.

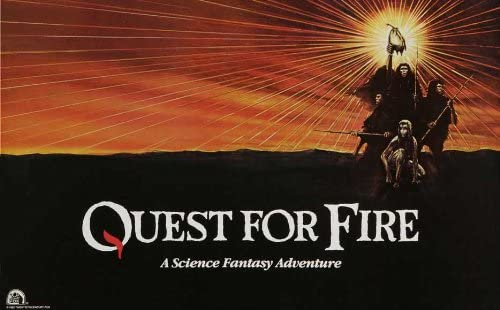

Yet it was Jean-Jacques Annuad’s Quest for Fire (1981) that captured my lasting curiosity because of its lobby poster featuring a mostly black image topped by three illustrated people, the tallest of whom is holding a blazing lantern.

At base, Quest for Fire is about a tribe of primitive people. When they are attacked by a more ape-like group and driven from their cave, they lose their warmth and life-giving flame. Three members of the tribe, Naoh (Everett McGill), Amoukar (Ron Perlman), and Gaw (Nameer El-Kadi), are sent to find a new source of fire, and they slowly traverse ancient Europe, encountering wild animals and variously hostile tribes, including cannibals. Along the way, they save a woman, Ika (Rae Dawn Chong), and finally bring fire back home.

The four main performers spend the movie’s length under layers of creature make-up. Nao, Amoukar, and Gaw have prominent brows, thick wigs, and dental prosthetics, and they perform with the kind of knuckle-dragging gait more often seen in a zoo. Their bodies express constant hesitation and confusion, and they often pause in circular protective formations like any herd of grazing animals. Plus, they wear animal skin jockstraps while Ika, the lone female, spends the whole movie naked but for a glaze of blue mud with black striping.

Setting all feelings about human nudity to one side, the constant presence of naked flesh is what makes Quest for Fire seem both exploitative and nearly ridiculous until a person remembers that we’re looking at a much older concept of social mores than what we know in the present. On-screen we see people grooming and eating whatever foods are available. Discernible types of hominid groupings appear, each with certain advantages and associated weaknesses—and with different levels of body ornamentation, body hair, and aggressive custom—but the most important single fact is that there is no modern language in the movie; nor are there subtitles.

We are transported into a time many thousands of years ago when people lived short, brutish, difficult lives. Threats and pain abound. Local groups gesture and grunt to communicate basic need, whether sexual appetite or hunger, and these people are fully exposed to the elements. To one way of thinking, it’s a horror scape, this planet Earth.

But there is a lot of attention paid in the film to terrain, to flora and fauna, the kinds of details most of us ignore in our cars and buses, as we travel across the tamed space of our mostly suburban lives. These characters, rather than coasting through the environment, separated by plastic and metal, hike and climb through it, hiding and waiting in moments of duress, and we watch them behave in the most inglorious ways, whether its chewing on the lice in a fellow tribe member’s hair or urinating on rocks. In these sequences, some viewers will feel shock at the nerve of Annaud and his cast and crew to spend time detailing normally private functions, though other viewers will equally feel heartened by the courage to explore obviously non-blockbuster material.

No doubt various liberties were taken with how to present the different developmental plateaus among early people; one tribe consists of upright orangutan-like cannibals while another consists of mostly tall, thin, African-seeming marsh people. Nor do all the special effects work, as in the wooly mammoth-costumed elephants that appear in the back third of the journey.

Despite these limitations, most viewers remember two key scenes. In the first, Naoh is bitten on the genitals by a rival tribesman who he kills. Then, after he recovers and establishes mating rights to Ika, she twists around on him during a sexual encounter to teach him the pleasures of performing face-to-face intercourse. We’re not in the grindhouse because the action is motivated by events in the characters’ odyssey, but the fact of dramatizing these blunt experiences is certainly what makes this nearly silent movie a kind of experimental classic.

–October 31, 2019