Surviving (adjective): remaining alive, especially after the death of another or others

Home (noun): 1- the place where one lives permanently, especially as a member of a family; 2- an institution for people needing professional care; 3- the goal or end point; 4- the place where a player is free from attack; 5- a game on a team’s own field or court

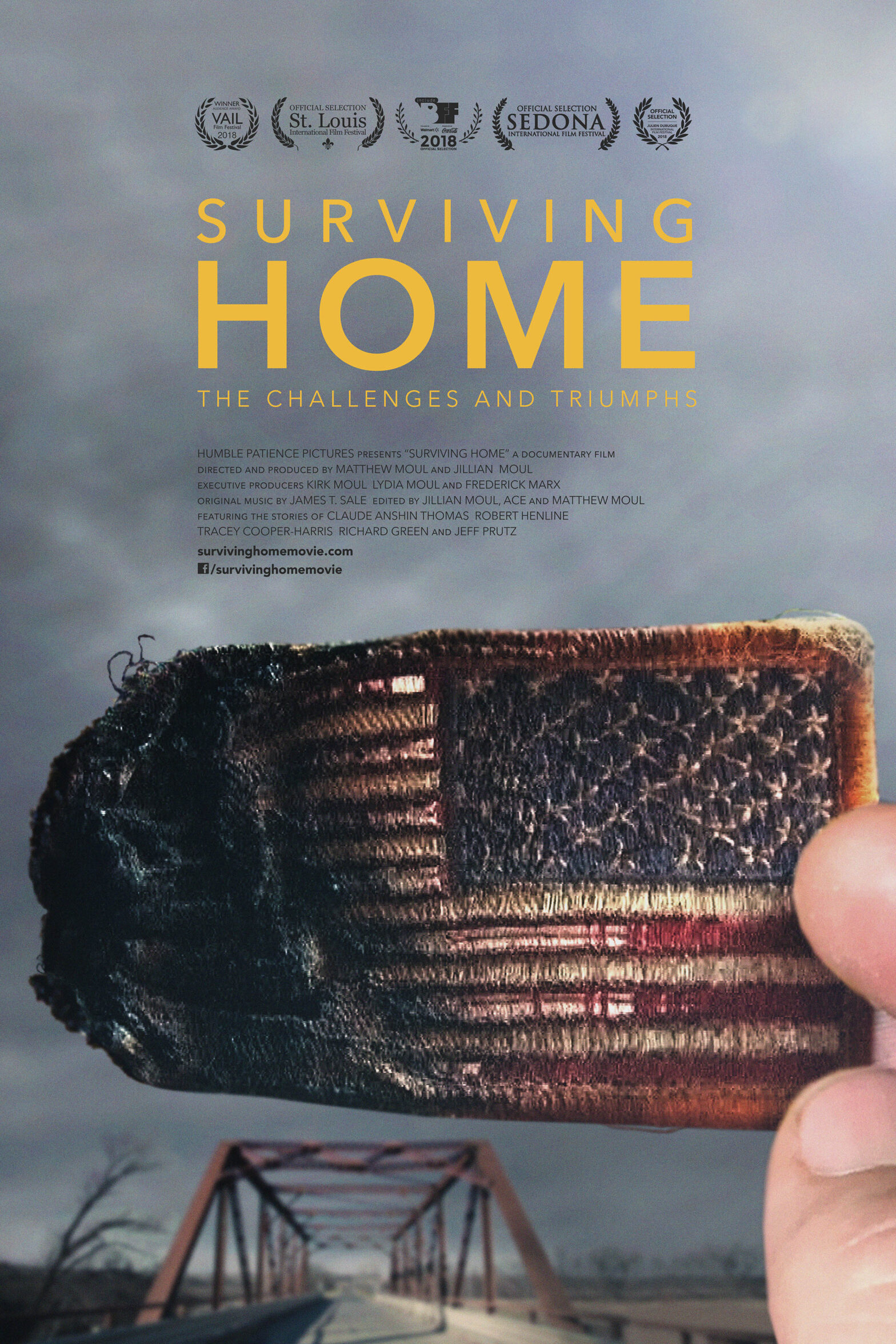

Filmmakers Matthew and Jillian Moul began documenting the movement of active duty military personnel back into civilian life in 2008. The project’s impetus stemmed from family connection with military service and an unsettling experience observing a stranger in acute emotional and physical distress. Building on these sources of inspiration, and using the know-how culled from years as TV and movie editors, the Mouls engaged in a 10-year odyssey that evolved into a multi-generational study of the aftermath of war called Surviving Home (2018).

Punctuated with lovely time lapse photography, Surviving Home presents found footage, original interviews, and verité segments to showcase veterans’ lives. The through line is building bridges, whether literally in the several bridges we see sprinkled across key moments, or through metaphorical connections made among veterans and between veterans and the civilian population. In short, Surviving Home considers the difficulty of transitions, both into and out of the military, and into and out of irreconcilable experience.

The documentary begins with Claude “Anshin” Thomas, a Vietnam-era veteran, and a third-generation military volunteer, who ran aground of substance abuse problems upon his return home. After years of dangerous habits, a broken marriage, and lost hope, Anshin was encouraged to study Eastern philosophy. Now a Buddhist monk, Anshin leads retreats for veterans, seeking to integrate feelings about past military service, particularly of traumatic events, that can be analyzed and endured through mindfulness that focuses entirely on what can be repaired, now. Anshin’s example is provocative because he addresses the lineage of military service that often runs in families, and he equally suggests the value of telling stories, of learning to accept responsibility for past actions while building a future that has no need for violence. Anshin is an activist, teacher, role model, and spiritual leader, but he is also a veteran with a deeply felt drive to render health from suffering and hope from despair.

The next “character” is Robert “Bobby” Henline, survivor of a roadside IED explosion in Iraq that blew off his left arm and left him burned across much of his body. Bobby’s story widens the documentary’s view to include Bobby’s family, all of whom remain present in his life, including his children, working to manage the physical and emotional pain that his healing and homecoming require. Interestingly, Bobby is also very direct and honest about the physical difficulties he faces. In several sequences we watch him visit his doctors, seeking care, and we also see him turn lived trauma into the basis of a professional comedy act that he uses to bring public attention to being a “Wounded Warrior.” In this way, we see Bobby forming a new community and vocation, and we watch as his injured body is repaired through skin grafts, dental implants, and fitting-out with a prosthetic arm.

A quieter story about inter-generational connection centers on two friends, Richard Green, a World War II-era sailor, and Jeff Prutz, a young former Marine. Jeff looks up to Richard because Richard reminds him of his family’s long history with the Veterans of Foreign Wars, the organization through which Jeff and Richard socialize while working to support fellow service members. This part of Surviving Home helps us see Richard through Jeff’s eyes, as a man with invisible service-related injuries, which have contributed to intense isolation and poverty. We also learn how poorly treated veterans from earlier wars were through Richard’s stories of being misunderstood and incarcerated, rather than being offered assistance and care. There is sadness in this set of memories, but we equally share in a beautiful moment when Jeff arranges for Richard to receive a new car to help reconnect with the wider world.

The final “character” in Surviving Home is Tracey Cooper-Harris, an Army veteran who survived war service and military sexual trauma related to her identity as a lesbian. Through Tracey’s story, the documentary connects with larger Civil Rights issues like LGBTQ advocacy because Tracey’s civilian transition included becoming lead plaintiff in a case concerning family benefits for Queer service members. Her case was eventually heard by the U.S. Supreme Court, which declared parts of Defense of Marriage Act unconstitutional, allowing Tracey and her wife to enjoy Veterans Affairs benefits, together. Tracey and Maggie evolve from being young people in love to being communal leaders, and they lean on each other for support, finding useful ways to fight through insensible obstacles to become more hopeful people.

Each of these four primary stories unwind across years. The Mouls kept their cameras rolling, acquiring original material while doing research into useful found footage and Fair Use imagery, and we learn a lot about each focal veteran, including the fact that homecoming is a chronic condition of adjustment and occasional setback.

In other words, being a “veteran” is not a garment to be worn or discarded. It is an existential reality that requires reflection and demands patience. There are simply too many memories and behaviors that have to be thought through and controlled, and much of that balancing act is very hard for many civilians to understand without first learning about the truth of real veterans’ experiences.

The larger purpose of Surviving Home centers on helping viewers find supportive communities despite occasional feelings of confusion or estrangement that sometimes overwhelm. Through modelling, on-screen, how people can re-integrate into society, the documentary shows several veterans reconciling difficult situations with healthful living. By focusing on the complicated but little seen process of military homecoming, Surviving Home also shows pure civilians how small acts of empathy form a more equitable world. In this act of telling, this will-to-presence through narrative, our veterans can be heard, not merely as stereotypic placeholders, but as people worth listening to because their experiences demonstrate some of the highest aspirations we possess as a people.

–November 30, 2019