“Get your hands on your heads, get off the bar, and get on the wall!”

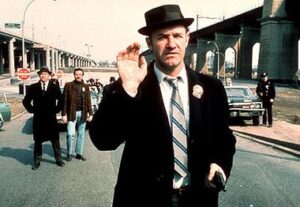

Gene Hackman has long been a personal favorite. Perhaps it’s his speaking voice that echoes a spot in my memory about educated, mid-western speech. Maybe it’s the rough-hewn physical presence with a receding hairline and wily eyes that see more in a glance than they reveal in a single spoken word.

Regardless, Hackman’s portrait of “Popeye” Doyle epitomizes the man, although I’m not sure it’s actually his greatest achievement, especially when considering the stunning array of roles in his long career.

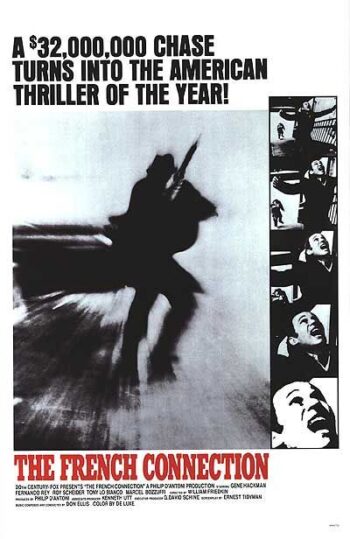

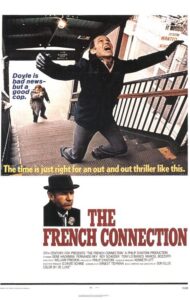

Pairing a sloppy, physical persona with an adaptation of Robin Moore’s source novel by celebrated screenwriter Ernest Tidyman resulted in producer Philip D’Antoni’s runaway hit for 20th Century Fox. Tagged with the phrase, “Doyle is bad news – but a good cop,” director William Friedkin managed to fuse an exploration of then-current police narcotics practice with a new set of formal considerations in The French Connection that broke new ground in American movies.

Concerned with shutting down an international heroine, Fernando Rey plays Alain Charnier, a former Marseilles dock worker-turned-narcotics exporter. His buyer is an up-and-coming Brooklyn criminal named Sal Boca (Tony Lo Bianco) with the investment capital of a Manhattan criminal heavyweight named Weinstock (Harold Gary).

Into this intrigue steps Popeye Doyle and his partner “Cloudy” Russo (Roy Scheider) who are first seen staking out low-level drug peddlers in Brooklyn. After playing a hunch to tail Boca after seeing him at a nightclub, Doyle and Russo lobby for time and resources to run a sting operation. In so doing they gradually learn of the extent of Boca’s connections with Charnier until their pursuit results in a final, bloody confrontation.

What sets apart Friedkin’s movie from its cinematic ancestors is its detail of police corruption. Popeye and Russo are good cops, even the best at what they do, precisely because they rack up arrests using violence, terror, intimidation, and illegal search and seizure largely focused on minority groups they pigeonhole with the most incendiary language possible from “nigger” to “spic.”

The sense of screen disaffection with civil authority doesn’t end with its consideration of beat cops and narcotics detectives. Instead, The French Connection touches on the early 1970s belief in bureaucratic malfeasance with a weak judicial system that overlooks criminal activities while holding fast to evidentiary proceedings in the courts rather than the leveling power of the street.

By film’s end, after Doyle and Russo move in to capture Boca, Weinstock, and Charnier, and after Doyle kills a rival FBI-investigator in a fit of confusion, there is a scrawl explaining what happened to each movie character. Having already seen Boca shotgunned in the confrontation, we learn that his wife and brother received reduced sentences, a French drug mule was incarcerated, Weinstock was released for lack of evidence, Charnier was never caught, and Doyle and Russo were reassigned out of the narcotics division.

Cynicism never met such a hammer of indifference. The film ends without any sense of comeuppance, so enjoyable in most cop movies with their reliance on bad guys being brought to justice, if not outright extermination.

This distinct theme of a world gone awry running throughout the film is also reflected in its technical execution with a disjointed editing style that won an Academy Award along with a sound mix that builds layers of diegetic sounds from inside scenes with dubbed dialogue, sometimes to confusing effect. Camera movements are jarring and often rely on hand-held devices or moving dollies and cars to carry the recording equipment at a fast pace as Doyle and Russo pursue their prey. Urban environs pepper the movie with slang, the painstaking efforts of police surveillance are considered, and the trouble of stopping criminal undertakings that one step ahead of the law is put into evidence.

While I’m impressed by this fusion of a directorial vision about the position of modern cops in a modern world, I can’t help but think The French Connection benefited from the originality of its execution rather than from its basic story. In short, the film is “just” an action movie about police, but its kinetic camera work, rough dialogue, occasional bursts of seemingly gratuitous police-related gore, and overall editing style has formed the basic grammar of movies ever since.

As one example, The French Connection is famous for having produced one of the most extraordinarily effective car chases in cinema history. That chase follows Doyle’s tail of Pierre Nicoli (Marcel Bozzuffi), Charnier’s enforcer, and begins outside Doyle’s Queens apartment building, continuing underneath an “L” until a shoot-out conclusion. Along the way numerous immovable objects are crushed beneath Doyle’s crazed driving, just as Nicoli kills two men in a subway car. By their final confrontation, Doyle shoots Nicoli in the back, thereby contributing the poster-image often associated with the film.

This car chase is still exciting despite all the years of rip-offs and attempts to outdo it since 1971. Friedkin, himself is among this group of latter-day competitors, who specifically attempted to outdo his earlier work in To Live and Die in L.A. (1985).

What sets apart this car chase through Queens County is that some of the most harrowing stunts in the chase weren’t staged at all. Shot on location and scheduled for one day of production, the barricades and cross streets were blocked off only minutes before the stunt drivers began their one-shot take. Due to the complexity of the shot, not everyone involved received word to start shooting at the same time. As a result many of the near-death moments were, in fact, near-death moments.

For example, a woman crossing the street with a stroller is nearly hit by Doyle’s racing car. After her brush with death that woman went into shock but since there were no injuries there was no need for a re-take so the recorded footage made it into the completed film. The car crash at the intersection of Stillwell Avenue and 86th Street was also unplanned and included in the final sequence because of its realism.

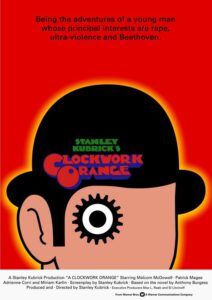

Ultimately, any assessment of The French Connection has to consider the other films it beat out for awards to muscle its way into memory. In addition to beating out A Clockwork Orange (Stanley Kubrick), Fiddler on the Roof (Norman Jewison), The Last Picture Show (Peter Bogdanovich), and Nicholas and Alexandra (Franklin L. Schaffner) for the Best Picture of the year award for 1971, it managed to eclipse a remarkable list of non-nominated films as well.

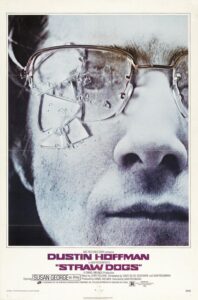

Don Siegel’s Clint Eastwood picture about another kind of maverick cop, Dirty Harry, was released to considerable outrage, commercial success and public excitement. Robert Altman continued his genre re- and de-mythologization and released a new kind of western with McCabe and Mrs. Miller. Likewise Mike Nichols gave Jack Nicholson a vehicle for male bitterness in Carnal Knowledge, Sam Peckinpah unleashed his visceral tale of a recluse intellectual-turned-embattled defender of house and home in Straw Dogs, and Clint Eastwood parlayed his superstar status into a directorial debut about a woman’s fanatical attachment to a radio personality in Play Misty for Me.

Altogether it was not a good year for representations of womankind, nor was it a particularly big year for women’s performances. Yet it was a sign of the times to see virtually all the award-winning movies and box office hits circling on the notion of masculinity in crisis. Significantly, it was Hackman’s Popeye Doyle and The French Connection that was singled out as being the mark of the moment.

Judging history through the eminent perfection of hindsight is a shifty business. Similarly judging the values of a previous time using the prism of current thought and cultural orientation sometimes leaves out what actually happened.

It’s often posited that the ‘70s were a time of rather striking formal, thematic and subject-oriented experiments in American cinema due to economic pressures and competition from non-traditional sources. Into this period were filtered the influences of television, advertising, various foreign film movements, the popularization of documentary practices, journalistic tendencies in all the media and even the cross-fertilization of such underground expressions as pornography and musical concerts. Pollinated by these practices, many films of the ‘70s, The French Connection included, were shockingly original in terms of subject, theme, and craftsmanship.

Still, Popeye Doyle is representative of his moment because he’s an anti-hero in the truest sense of consideration. His struggle in the world is defined by blindly courageous confidence that makes him simultaneously despicable and charismatic with a working class patois to boot.

He may not be likable, but his French connection is a defining moment for all action-adventure movies.

–August 31, 2018