Take 1: “I always heard there were three kinds of suns in Kansas: sunshine, sunflowers, and sons-of-bitches.”

Take 2: The Outlaw Josey Wales presents a bicentennial celebration as secessionist apology.

Take 3: From “The Hi-Lo Bro Show” podcast: “This is the one where Richard recalls Bleeding Kansas, Garrett professes man-love for Clint, and revisionism is explained–sort of.”

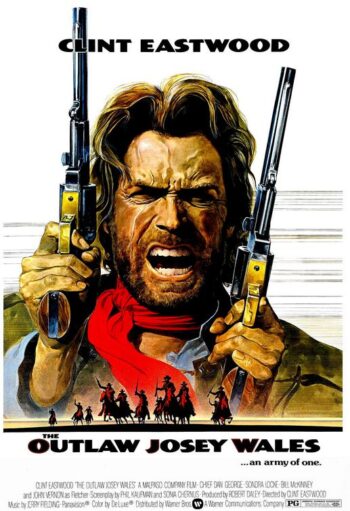

Take 4: Without doubt Clint Eastwood, at age 46, was one of the world’s most impressive models of male physical beauty. Fortunately he committed thousands of images of himself to his film in The Outlaw Josey Wales both to tell a story but also to document the fact of his undeniable physical person. The year was 1976 and in the title role Eastwood glossed fantastic as a farmer turned outlaw hero complete with numerous pistols, a vertical scar across his face and those squinting eyes you know were meant for more than murder.

Opening with an idyllic prelude before the credits sequence, Josey is scene working the land with his son, Josey Jr. (Kyle Eastwood). When the boy is called away by his mother to wash for dinner Josey returns to work alone but pauses amidst the patter of horses and a smoke plume rising from the nearby trees in the direction of home.

He runs from fear and anticipating evil but arrives too late. Beat up and thrown to the ground Josey is witness to his wife’s rape and murder, his son’s killing and the burning of his home after being left for dead with a nasty gash across the face. All that’s known to him as he later buries his family is that the killers are a group of Union soldiers led by “red legs” Terrill (Bill McKinney) because of his reddened boots. Picked up by a band of Missouri bushwhackers Josey joins their cause of killing a few Union soldiers to even the score.

In precious little on-screen time, and with very little dialogue, Eastwood manages to convey Josey’s fundamentally peaceful nature and his just cause for vengeance. Plus, he’s able to show his hero’s skill with a pistol along with giving him the urgency of a feud born across his face in the vertical scar of Terrill’s saber blow.

Over the subsequent credit sequence is a montage of Josey’s bushwhackers engaging northern armies to their occasional victory and constant peril. Again, it’s a testament of story telling without words where we learn not only the main cast and crewmembers but see Josey rise from anonymity into being a leader of men.

After much killing the group is enticed by the sober realism of one of their own, a man named Fletcher (John Vernon), who suggests they give up their arms and declare allegiance to the United States of America. In so doing, they will earn peace and the right to return home to Missouri since the Civil War has ended even if their personal vendettas remain unsatisfied.

As the outlaws ride to meet Senator Lane (Frank Schofield) and his division of soldiers led by the hated Terrill, Josey remains behind as a lone holdout for surrender. From a distance he sees the Senator’s plot unfold to gun down the former outlaws where they stand. Not quick enough to save them, Josey seizes a Gatling gun and lays waste to the Senator’s army before escaping with his life and that of a gut-shot young bushwhacker named Jamie (Sam Bottoms).

Gradually leading the Senator’s forces on a cat and mouse chase Josey believes his one-time friend Fletcher has betrayed him. In understanding that there are numerous patrols trying to find him, however, he rides with Jamie towards the Cherokee Nation to hide. Before they make good their escape, though, Jamie dies just as Josey meets Lone Watie (Chief Dan George), an aged Indian, and begins a cross-country trek to evade his pursuers on the way to Mexico.

Along the way Josey and Watie pick up a squaw named Little Moonlight (Geraldine Keams) and a number of pack animals from bounty hunters who try and fail to take Josey’s hide for the price on his head. They also end up in a frontier town and cross paths with a group of Kansans headed to a Texas, lead by Grandma Sarah (Paula Trueman) and her cowering granddaughter, Laura Lee (Sondra Locke).

After evading still more bounty hunters and Terrill’s small army, Josey’s group once again meets up with the Kansans, only this time after they’ve been ransacked by a group of goods trading comancheros. Watie falls captive and Josey rides in for the rescue, killing the comancheros but also being noticed by the Comanche who were the comancheros’ one-time trading partners.

Josey’s rag tag band finally pulls into the Texas boomtown only to find it’s been stripped mined of its wealth and population save a few odd stragglers. Quickly establishing their lives around the home of Grandma Sarah’s dead son, the group begins to relax and cultivate their domestic haven. Animal stables are built, living quarters are cleaned up, recreation is sought and religious services begin.

With blood lust on their mind, however, the lingering Comanche, led by their leader Ten Bears (Will Sampson), intend to raid the settlement and kill all the whites encroaching on their lands. Arming his friends with weapons and setting up a defensive perimeter, Josey rides off to meet his adversary with an understanding of the balance between life and death. Making a fast alliance, Josey and Ten Bears agree to peaceful terms and Josey’s outlaw past catches up with him once he consummates his affection with Laura Lee.

Terrill’s men confront him but learn of their peril too late. Aided by his friends who arm the homestead’s defensive perimeter, Josey wipes out Terrill’s band and runs “red legs” through with his saber before meeting up with Fletcher in a final righting of past wrongs. The two bear witness to a pair of Texas Rangers certifying Josey’s death and agree the war once so urgently fought by the bushwhackers is now over and the peace begun.

Tagged as being about, “…an army of one,” The Outlaw Josey Wales did a fair business at the box office with US grosses topping $22 million.[1] It continued Eastwood’s already-established outlaw character, and it breathed life into the big screen Western just then starting its decline into the 1980s.

The success of The Outlaw Josey Wales may rest on how it demythologizes the Western, while equally remythologizing that same form through Eastwood’s star persona. It also poses an allegory for the parallel times of Reconstruction and the Vietnam War-era, seen through the eyes of its screenwriters, Sonia Chernus and Philip Kaufman adapting Forrest Carter’s novel Gone to Texas.

By first setting the action in the midst of the Civil War, The Outlaw Josey Wales contradicts the usual point-of-view whereby Union sympathies are morally above reproach and the charge of manifest destiny is a necessary step in the expansion of the Eurocentric American project. Eastwood’s movie refutes both these assertions by making Union soldiers the literal embodiment of evil and cruelty in the film’s opening moments while also ensuring our sympathies towards the plight of Native American peoples. Most prominently this sympathy is won through the sympathetic portrayal of Lone Watie and Little Moonlight as the film’s supporting heroes.

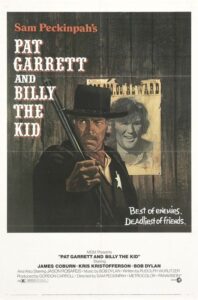

Later on it becomes clear that while the movie is offering a surprisingly effective critique of the Western convention, and by extension the American frontier myth just like Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (Sam Peckinpah, 1973), McCabe & Mrs. Miller (Robert Altman, 1971), and Little Big Man (Arthur Penn, 1970) before it, the film also slides easily underneath Eastwood’s “Man With No Name” persona to assert a new kind of traditional Western hero. This process includes the “army of one” ethos surrounding Josey Wales who is frequently presented as a killing machine yet also as a man with a sense of moral truth. By depicting corruption in the Old West Eastwood offers himself as star to give an alternative hero through Josey Wales who survives the film’s critique of its genre by smoothing over any rough edges with the trowel of an ultimately benign legend that hearkens to old times of justice and fair play.

Most strikingly, however, The Outlaw Josey Wales does a convincing job paralleling the dissolution of Native America in the Reconstruction Era with the American War in Vietnam. Thus, the Civil War’s winner, the American Union, is seen warring with widely unknown lands and subjugating unwilling peoples to the law of a foreign aggressor. Likewise these unwilling peoples become warlike and resistant, ultimately never fully kowtowing to the demands of the United States though not able to defeat it in battle either.

Into this fray is the group of Missouri bushwhackers who resemble both the Viet Cong and US Special Forces with a reliance on guerrilla tactics, maneuverability and confidence in the individual foot soldier. As the epitome of this fighting man, and perhaps its antithesis in the impregnable hero, Josey Wales is able to bridge two historical moments. He is a freedom fighter, a mourning father and husband, the pinnacle of states rights advocacy and a friend to the culturally marginalized because he is not just a character in the film but also one of its foremost narrative devices. In short he is a potent allegory of the 1870s and 1970s that asserts the fallibility of governments and of countries overstepping their bounds in the face of individuals who struggle for the right to live according to the demands of civility and peace.

That The Outlaw Josey Wales ends on a conciliatory note with Josey agreeing to end his war and fade into anonymity as a peaceful citizen is something of a cop out. But it’s also the only logical end to his feudal struggle once the innocent are avenged and the evildoers put to death.

Maybe it’s not the most liberal, or humanistic, theme possible in a film that is otherwise so open-minded when representing Native Americans and in its sympathy towards the American South of the 1860s, especially towards Southerners who wished for a small federal government rather than a large one. Yet the film’s themes of vengeance and frontier justice are not the most reactionary moral tale either since the necessary violence built-in to the outlaw Josey Wales’s character also bears the seed of creation. After all he was once a farmer with a family just as it appears he will be again with the bloody conclusion and the end of Terrill’s pursuit.

–April 30, 2021

[1] Other hits of 1976 included the Oscar winner Rocky (John G. Avildsen), the re-make of King Kong (John Guillermin), and Logan’s Run (Michael Anderson).