“In 1889, President Harrison opened the vast Indian Oklahoma Lands for white settlement.”

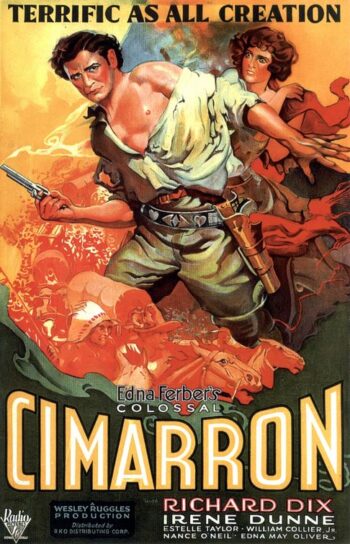

Described as being, “Terrific As All Creation”, Cimarron is a slight movie important only for having won the 4th Academy Award for Best Production, a title since re-named Best Picture. Now almost unwatchable, save for its sweeping vistas and set design, the movie’s empire building story was drawn straight from a best-selling novel by Edna Ferber.

Centered on Yancey Cravat (Richard Dix), a frontier lawyer, sheriff, newspaper editor, father, husband, spiritualist, civil rights agitator, and inchoate politician, the movie opens with the Cravat family moving to the Oklahoma territory during the historic land rush of 1889. This opening sequence, a truly terrific moment, establishes Yancey’s position as the head of his family and equally sets up his romance with big adventure that will carry him far from home, whenever narrative action flags.

Yancey’s wife, Sabra (Irene Dunne), a society woman, finds herself in a coarse world with young children to care for. At first hopelessly devoted to her husband but with needs that are obviously secondary to his, her subordinate story becomes more interesting as Yancey expresses his wanderlust.

One example of this intra-marital conflict is Yancey’s concern for Native Americans, whom he properly recognizes as having been robbed of a homeland and cultural heritage through the western expansion of European settlers. Sabra is unsympathetic to such sentiment, so Yancey is sanctified through his sense of social justice and willingness to defend the downtrodden, although his activist principles are easily overcome by periodic adventures that include a second land rush and participation in the Spanish-American war, collectively advancing the plot across the transformation of the Cravat’s hometown of Osage into a bursting metropolis, all at the price of taming the wild “Cimarron.”

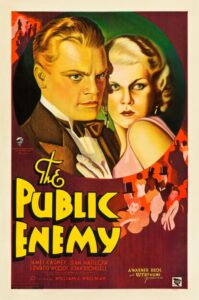

Winning the Outstanding Production top honors at the 1932 Academy Awards ceremony, Cimarron beat out East Lynne(Frank Lloyd, 1931), Skippy (Norman Taurog, 1931), and Trader Horn (W.S. Van Dyke, 1931), along with the first screen version of The Front Page (Lewis Milestone, 1931). Among unrecognized films of the time are such classics as City Lights (Charlie Chaplin, 1931), Little Caesar (Mervyn LeRoy, 1931), and The Public Enemy (William Wellman, 1931), and in the absence of these films from Academy Award recognition is a reminder that not only is Cimarron laughable, but it is hopelessly devoted to silent film conventions. Dix’s acting is a mixture of overlarge gesture and silliness. Vignettes depicting different years from 1889-1930 vary in quality. Howard Estabrook’s Academy Award winning script preaches the beauty of Yancey’s heroic stature at the expense of other characters, including a Black servant boy, Isaiah (Eugene Jackson), who appears as a Stepin Fetchit stereotypic figure, just as the presentation of Native Americans is, at best, marginal to the plot, despite Yancey’s periodic speeches, and, at worst, historically revisionist to flatter White audiences.

In the end, Cimarron is a museum piece that rewards the completist’s viewing impulses among archivists, although it will frustrate the search for pleasure among film enthusiasts.

–December 31, 2017