“What’s Belgium famous for? Chocolates and child abuse, and they only invented the chocolates to get to the kids.”

Movie violence is often funny, as in the accidental killing of an unimportant character, and profane dialogue frequently rises to great poetry, particularly because the F-word is useful in every grammatical mixture imaginable. Combine these two and you arrive at Neil McDonagh’s In Bruges (2008), the playwright-turned moviemaker’s debut feature following much stage success and his first-rate short film Six Shooter (2004).

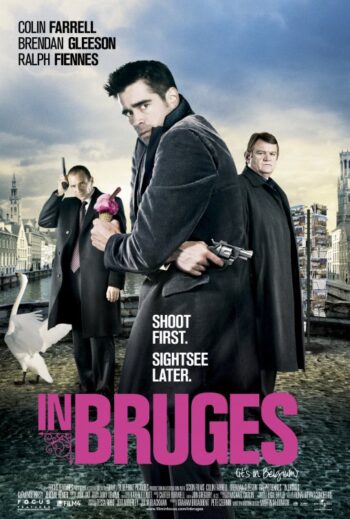

The setup is simple: two UK hitmen are on the run in Bruges, Belgium. Why? The younger man, Ray (Colin Farrell), accidentally killed a boy while assassinating a priest for his boss, Harry (Ralph Fiennes), and his mentor, Ken (Bredan Gleeson), is assigned to keep him quiet until they can return home. The problems quickly multiply because Ray has a habit of making himself conspicuous while Ken truly enjoys sightseeing in their medieval sojourn.

This thumbnail sketch is both accurate and inadequate. Ray and Ken really are stir-crazy, and they don’t like each other. But the meat of the story forms around the people they meet as they argue and wait for Harry to release them, along with the situations that arise from these chance encounters that are filled-in with great conversation on the way to a truly, rapturously, and unexpectedly graphically violent conclusion.

A person will watch In Bruges because it’s streaming on a favorite media service, which is how I bumped into it, or because of its award-winning reputation, which is why I’ve known about it since 2008, or because of the comic dialogue that is so totally un-PC. Ball it all up together and you’ve got a ready-made cult classic that features the beauty of Colin Farrell at the waning end of youth, the soulful kindness of Brendan Gleeson, and Ralph Fiennes playing a dim bulb of evil (call it Voldemort light).

Ray is as blunt as any street smart, uneducated person can be, and Ken is wise in the ways of the world, understanding the virtue of loyalty while holding his profession in disdain. The craft of murder isn’t presented directly and a reverence for history, for the dual nature of human experience, is impressed into the design of the film that includes direct reference to the Hieronymus Bosch painting “The Last Judgement” and frequently allusion to another-mystery-in-the-European-darkness movie, Nicholas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now (1973).

While the heart of In Bruges is the nature of redemption, the soul of the piece is in daring to let occasionally brutal people speak to each other rudely and then talk, talk, talk their way into oddly endearing friendship.

–August 30, 2018