As exhibition spaces have shrunk from gigantic public theaters into pocket-held smart phones, viewing opportunities have proliferated. This sea-change has left many media people in the mode of worried hand-wringing, although everyday spectators seem pleased with the cornucopia. Yet the general point is true: watching movies is fun.

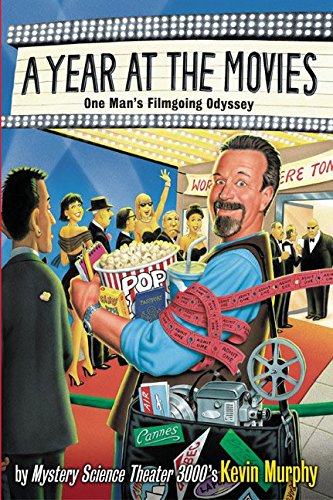

Reading about watching movies can also be fun. With so much material vying for our attention, it’s useful to find worthwhile guides to cut down on bad experiences in favor of good ones. Enter Kevin Murphy’s experiment in daily discipline-turned-record of a lost time, A Year at the Movies: One Man’s Filmgoing Odyssey (2002).

Famed for his work on Mystery Science Theater 3000, Murphy left the original run of that program feeling exhausted and disaffected with movies. To find his true north he organized a restorative project: he would see at least one publicly exhibited feature film every day for a year while trying to experience as many kinds of movies, theatrical venues, and movie-going experiences as possible, and he would write a book to summarize his experience. Along the way Murphy passed a kidney stone, traversed several continents, carried with him a projector and trove of silent movies on celluloid reels, and generally made himself available for the experience of cinema, whether outdoors or in, among strangers or alongside friends, happy or sad. He sampled theater food, saw several movies more than once, went to date movies with dates, attended film festivals, worked as a ticket taker, visited the projection booth, and talked to people in the film industry, including theater managers, journalists, and students feeling their way through the discipline.

Plus, Murphy is funny. He’s also university trained. Together, then, his humorous intelligence lets him move easily between occasional allusions to high theory, or a knowing jab at Herman Melville, to clear expression of his dislike of the phenomenon we call The Rocky Horror Picture Show (Jim Sharman, 1975).

A Year at the Movies is organized into weekly updates listing the movies Murphy saw during that seven-day spread, including the theater, or space, where each title was screened. Consequently, we read his progress across the Midwest (Murphy lives in Minnesota very near the Mall of America) and across the world in venues that stretch across Australia, France, Italy, England, and the Cook Islands. Incidentally, the year of his project, which is 2001, overlaps with the release of lots of terrible movies, like Corky Romano, directed by Rob Pritts and starring Chris Kattan, or Lara Croft: Tomb Raider, directed by Simon West and starring the then-newly established Angelina Jolie pout, along with a few masterworks, like Amélie, directed by Jean-Pierre Jeunet, and Monsters, Inc., directed by Pete Docter, and the world-changing shock of the 9/11 attacks.

Through it all, Murphy affirms that watching movies is fun. Which is wonderful news for this reader, who agreed with that premise before opening the book, but took from it several takeaways: a cinephile should visit the Midnight Sun Film Festival in Sodankyla, Lapland, Finland, and it’s worthwhile to pull older movies off the shelf, including the Jimmy Stewart/Margaret Sullavan vehicle The Shop Around the Corner (Ernst Lubitsch, 1940), the Iranian melodrama A Time for Drunken Horses (Bahman Ghobadi, 2000), and the documentary Home Movie (Chris Smith, 2001).

In the end, A Year at the Movies is a snapshot of something that’s now all-but-extinct: moviegoing in public. Much can be said about the coarseness of life among screens in the world of today, all the missing eye contact and atomization. Less is typically conferred on the memory of togetherness that was, for many years, the essential feature of the most popular mass entertainment in the world, movie-going, which once required people to sit together, listening to one another emote and react, while watching stories projected onto a smooth screen in the dark.

–October 31, 2018