“78 Shots & 52 Cuts that Changed Cinema Forever”

Film studies is reducible to several main approaches: aesthetic-technical, theoretical-ideological, self-reflective, socio-cultural, and/or obscurantist-celebratory.[1] In all five approaches, the point is expressing pleasure, for if a person doesn’t feel drawn to thinking about movies, there is no reason for any film studies project. But if a person does feel drawn to thinking about a movie, or a filmmaker, or a film movement in history, then these five approaches provide ways to better understand the pleasure of movies.

This is not to say that all pleasure is yoked to happiness and good vibes and reassurance. In fact, much pleasure derives from recognizing the range of emotional responses, from loathing through love, which are caused by something at once so complex and simple as a set of serially expressed images accompanied by sounds that tell a story.

As a film teacher, I spend a lot of time encouraging students to think about the emotional reactions they have to movies, and then how they can describe these reactions through phenomena they observe. I like presenting the baseline that no one can invalidate any emotional responses. Instead, a good film study helps a person marshal evidence concerning what they see and hear to figure out how a movie works on them, why it’s doing what it does, and whether the underlying emotional response can be explained.

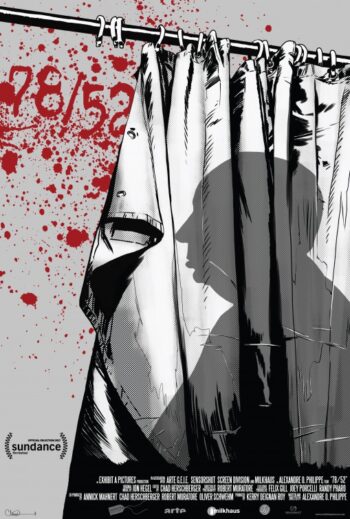

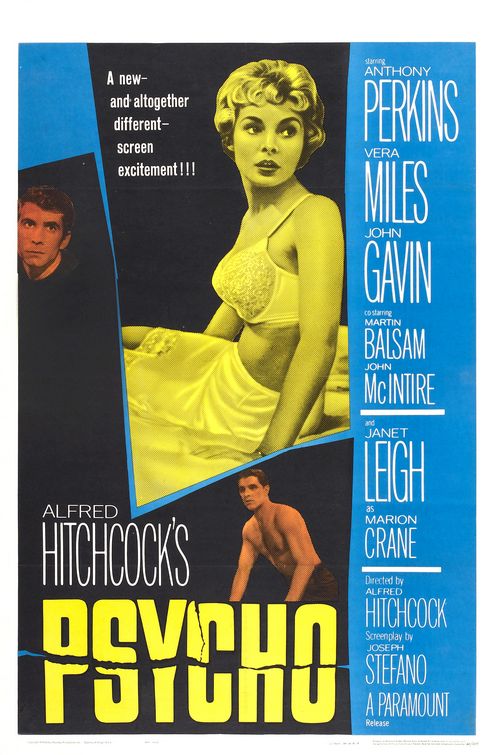

Alexandre O. Philippe’s 2017 feature documentary 78/52: Hitchcock’s Shower Scene is a perfect film studies project. As a film school-educated moviemaker, Philippe’s project works out some of the many ways in which Alfred Hitchcock’s peculiar genius is expressed in the 78 camera set ups, or shots, and 52 cuts used in the famous shower murder from his movie Psycho (1960). To aid this investigation, Philippe recruited dozens of talking heads to get down into the weeds of how this scene was constructed and why; what it’s immediate context was; what Hitchcock’s intentions seemed to be; where and how the scene influenced the history of movies; and how pleasurable it is to be fully emerged in answering these questions as the stuff of one more movie.

The roster of interviewees begins with Hitchcock, himself, who is present through many TV interviews, voice recordings, and still photographs that were captured while he was alive. We also listen to the curator Timothy Standring, novelist Bret Easton Ellis, movie historian David Thomson, movie directors Karyn Kusama, Peter Bogdanovich, Eli Roth, and Guillermo del Toro, editors and sound designers Gary Rydstrom, Chris Innis, and Walter Murch, composer Danny Elfman, body double Marli Renfro, and the Psycho star Janet Leigh’s daughter, Jamie Lee Curtis. All of these interviewees discuss the shower scene and its meaning, and each one squares the pleasure they each feel, whether dread or satisfaction, while respecting the constructed nature of this signature moment.

Interestingly, Philippe’s documentary is aesthetically remarkable, too. It uses reconstructions and re-enactments that mirror moments from Psycho, along with presenting the typical newsreel inserts we expect in a documentary, and it does much of this work with Black and White photography.

The real charm of the movie is the interviews, in which many interviewees are situated inside Marion Crane’s room at the Bates Motel. Our experts are fully inside the echo chamber, reflecting on what makes Psycho great, while sitting where Marion breathed her last, thinking about how that scene was built from so many setups and cuts, and the typical interview consists of at least two angles on the interviewee.

In the first angle we meet the likes of Easton Ellis, Kusama, Murch, et al., and they speak to a never-heard from and never-seen interlocutor. This is typical in documentaries; we observe answers to off-camera questions, and our point-of-view is outside the eyeline of the interview, just to one side of the presumptive conversation we are part of, but also excluded from. Then Philippe has each interviewee watch the shower murder on a TV screen while the camera sits just above the TV, aimed at the interviewee in nearly direct address, so we can watch their eyes scan the screen while they mutter whatever thoughts bubble up.

On top of this technique, which is constantly broken up by linked observations about the pre-history of the sequence, or the context of its production, or the public reaction to it, we see the shower murder pulled apart into its many clip and sounds, and never run, whole, from start to finish. In this way and fully explained by expert-fans, each moment in the murder becomes more freighted with meaning; the feeling that any movie is happening “right now” is replaced with a sober examination of how planned this one scene really is, underlining how much ingenuity, work, and refinement is built into any movie or any resulting film studies project.

Along the way we learn that shooting the shower scene was supposed to take two or three days, which bloomed into a seven-day trial of setups, modifications, and re-takes, until editor George Tomasini had the necessary material to express horror, eventually scored by Bernard Herrmann. Through close textual analysis the final scene is shown to be a wonderful mix of abstractions, interruptions, screen storytelling rules both observed and ignored.

Philippe’s documentary ends up being a persuasive bit of cinematic journalism that enlivens the fantasy of movies as magic, since that shower scene is so memorable, while also revealing the mysteries of what happens behind the velvet curtain. True fans of behind the scenes documentaries and Hitchcock’s career will find moments of wonder. But 78/52 is an equally solid way for the general viewer to engage in an investigation about the source of pleasure in the horrors of Psycho.

–February 28, 2020

[1] In the first camp, we consider the techniques that make a movie sound and look the way it does; in the second, we consider how a movie produces themes and elevates particular ideas about beauty, power, and order; in the third, we think about ourselves as people formed by a relationship with movies; in the fourth, we look at how movies are symptoms of wider societal currents; in the fifth camp, we venerate objects of affection, regardless of quality.