“I started to tell him the story of the movie, and as I did, all the emotion came back. I didn’t want to cry in front of the boy, but it was impossible; there I was, crying out loud in the courtyard, and I told him the whole drama to the bitter end.”

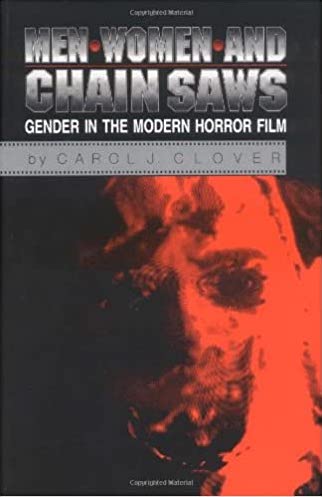

Carol J. Clover’s 1992 book Men, Women, and Chainsaws changed my life. I bought it with some birthday money while perusing the stacks of the USC bookstore just after my first year of college was ended, and I fell in love. Across 260 pages, Dr. Clover describes various tendencies in American slasher movies, which were a central part of my audio-visual diet from ages 14-17, and she performed this academic study with the kind of close textual analysis usually focused on more “elevated” works from European masters than low budget material aimed at the grindhouse. Her central idea, now part of the firmament of screen storytelling, specifically, and film studies, generally, is that the “final girl,” a smart, singular, and virginal, but always capable, character, is often the survivor of horror movies because she is uniquely suited to defend against whatever monstrous or evil force has been dreamed up to assault her.

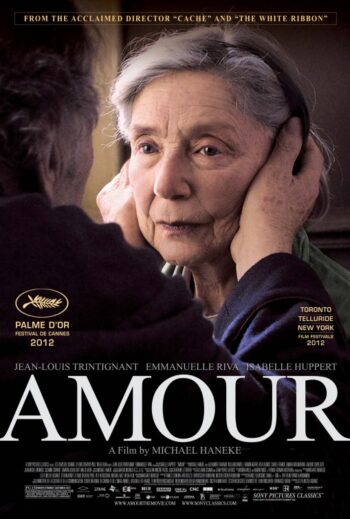

I was thinking about Clover’s book when recently screening Michael Haneke’s Amour (2012) that tells the story of a decades-married older couple struggling to deal with their advancing old age, including her stroke, paralysis, and dementia, and his forced caregiving. There is no obvious parallel between this movie and the likes of Clover’s final girl, whether Sally Hardesty (Marilyn Burns) in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (Tobe Hooper, 1974), Laurie Strode (Jamie Lee Curtis) in Halloween (John Carpenter, 1978), or Nancy Thompson (Heather Langenkamp) in A Nightmare on Elm Street(Wes Craven, 1984). Yet I was overcome by a sense of trope revision in the final girl, which has been adjusted by a male filmmaker, Haneke, to accommodate an unusual and atypical form of horror story, the depiction of senescence.

In brief, Michael Haneke is a well-established, highly respected Austrian filmmaker who is considered quite influential, although not in the popular cinema where his techniques are thought too cerebral, or, to use a kinder synonym, ascetic. Amour makes evident these formal preferences, including the use of long takes consumed with everyday detail (preparing meals or performing physical therapy), unswerving study of vulnerable activities (bathing or expressing upset), a purposeful lack of sentimentality about story development (growing older is painful), and a commitment to avoiding a musical score to push emotional responses in viewers.

Amour, like growing old, isn’t for wimps. It’s a hard movie that begins with the Parisian police breaking into an apartment where an old woman is found dead, surrounded by flower petals, on her bed.

We flashback, perhaps a year, when we are introduced to retired 80-something musician-teachers Georges (Jean-Louis Trintignant) and Anne (Emmanuelle Riva). They attend the concert of a former student and return home, where it appears someone tried and failed to break into their apartment. Anne has a nightmare and the next morning, over breakfast, she has a stroke that renders her catatonic. Georges makes ready to take her to the hospital when she seems to recover herself, only to realize she lacks motor control.

Shifting forward, Georges brings Anne home from the hospital where a procedure to unblock her carotid artery has failed. Anne tries adjusting to her new wheelchair bound state and asks George to promise to keep her at home, no matter what. The couple learn to re-organize their daily habits, like shopping and reading newspapers, and Anne fights depression, even trying to commit suicide.

When their daughter Eva (Isabelle Huppert) visits, commenting on the increasingly homebound condition of her parents, Georges put on a good face while forecasting the inevitable. He hires home nursing aides and gamely works to help his wife carry on while tending to his own emotional reservoirs of health and well-being.

Eventually, Anne loses control over her mental faculties, as well as her bodily functions. She spends her waking hours crying or groaning, which distresses Eva in occasional visits, while Georges rather fatalistically tells Eva that all they have to look forward to is the end.

One afternoon Georges calms Anne during a screaming fit. He tells her a story from his youth, and when she stops screaming, he smothers her with a pillow. The rest of the movie is spent watching him seal up the apartment.

In Clover’s analysis of the final girl, a group of young people is hunted by some criminal, monster, or evil force. Picked off, one by one, for their moral and practical flaws, including risky behavior in far flung environments where there is no outside help, an eventual last target emerges, the final girl, who, in the best of the tradition, defeats the malign force with perseverant suffering, guile, and luck.

Amour seemingly embodies none of these traits, until the axis is pitched 180 degrees to consider Georges as the modern avatar of type. He’s the last person capable of handling, standing up to, and overcoming the creep of death that overtakes his wife, and his caregiving isolates him from the prying and helping hands of others.

The more typical Cloverian parallel, and one that is valid as far as it goes, is seeing Amour as Anne’s story. At first, she’s lively and prickly, then disabled and strong-willed, then semi-vegetative and complaining. From this angle, all the agonizing long shots of physical accommodation, whether to her wheelchair, the halls and doorways of the couples’ apartment, or to the bedwetting and assisted living, is the set of trials that she must survive, the stuff of her stiff backbone. But she does try to kill herself after she’s ushered Georges from their home to attend the funeral of a friend, and this moment is the inflection point of the movie.

When Georges returns home, he finds Anne sitting on the floor beneath an open window to the courtyard below their upper floor apartment. Her wheelchair rests near her, and she can’t get up. She asks how the funeral was, and Georges explains that it was an undignified disaster, never once commenting on the implied fact of Anne’s planned self-harm.

From that point, the point-of-view shifts from favoring Anne, the victimized octogenarian, to Georges, her caretaker, and the final girl pattern switches genders and generations, and also changes the nature of brooding evil into the affliction of age. Where Carol J. Clover saw the psycho-sexual inscription of male aggression, fear, and violence on the protracted suffering of a strong girl, who is never quite a woman because she’s a virgin, Amour inscribes male aggression, fear, and violence on the protracted suffering of a strong old woman, no longer the girl originally loved by her aged husband, which requires viewers to wrestle with whether Georges smothering his wife is an act of merciful generosity or selfish relief.

In the event, Amour is a tough, rigorous movie that examines the little-seen stuff of long life that each of us presumes is our privilege until we reach the age when more of life is behind us than before us. It’s also striking that the moral certainties typically applied to stories of close personal violence are suspect in this movie that carries the title, “Love.”

–February 28, 2020