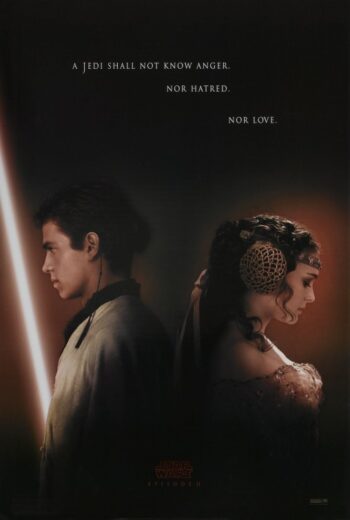

“I’m in agony. The closer I get to you, the worse it gets. The thought of not being with you- I can’t breath. I’m haunted by the kiss that you should never have given me.”

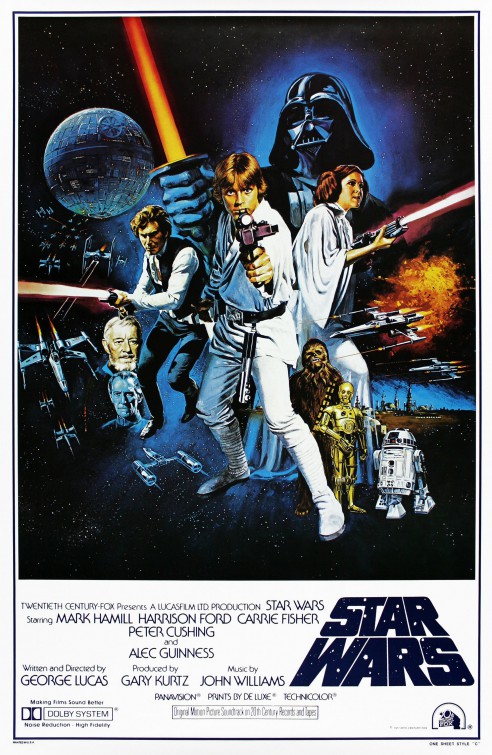

I grew up on Star Wars, the George Lucas-directed, game changing space opera from 1977. It was the first movie I remember seeing in a movie theater when I was four, and I spent the reach of my pre-teen years collecting as many of the Kenner 3-3/4” action figures as I could finagle, purchase, or swap for, and I still have all of them, weapons and capes included. To say I’m fully invested in, “A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away,” is an understatement; I once fantasized, quite three-dimensionally, on the virtues of piloting Slave I over a B-Wing fighter, and whether the Millennium Falcon is truly the fastest ship in the galaxy (ANSWER: it is not).

To watch the Star Wars prequel trilogy (1999, 2002, 2005) is to be split in two. On the one hand, I am returned to the state of mind of the 10-year old me, fresh from seeing Return of the Jedi (Richard Marquand, 1983) and wondering where the Star Wars universe will (should) unspool in the remaining years of my then-young life; but I am also aware of what adult me thinks when watching this dreck that I can’t any longer sit through without snorting or slapping my forehead every few minutes.

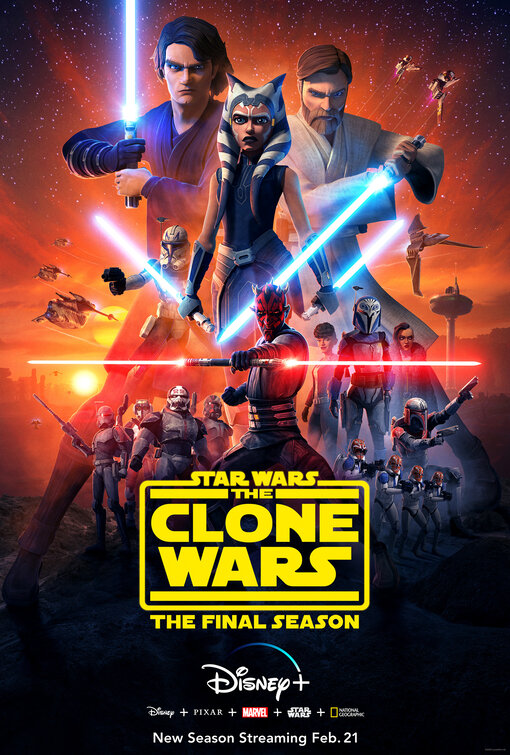

In context, I’m right now in the midst of re-watching all things Star Wars with my younger daughter because she’s discovered the TV show Star Wars: The Clone Wars (2008-2014, 2020) on Netflix. The trouble is, The Clone Wars may be the high-water mark for Lucasfilm’s many projects. The series employs all manner of fantasy design, from creatures to costumes and alien worlds through alien space craft in carefully produced, 22-minute long episodes. When an episode fails, just wait a few beats and something new will start. Often, I’m able to interpret episodes of The Clone Wars as a commentary on American electoral politics, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, developments in human genome research, the nature of artificial intelligence, and the continuing trouble of integrating unlike individuals into the mainstream of a working society. That my first grader digs it is a cherry on top.

Then there are the Lucasfilm feature films to contend with. Here, I’ll restrict my remarks to Star Wars: Episode II – Attack of the Clones (George Lucas, 2002), the midpoint of the prequel trilogy that directly precedes all 121 episodes in The Clone Wars, which is, again, the high point of Lucasfilm’s many projects.

We take as a given that young Anakin Skywalker (Haydn Christensen) is the fulcrum of galactic power because he’s uniquely situated to take on the role of ultimate good or evil, so gifted is he in the ways of the Force. Anakin is now around 20 and nearly a fully formed Jedi, but not quite. He’s romantically hung up Padmé Amidala (Natalie Portman) because, well, have you seen her? And a bunch of other nonsense moves along in the background to finally engineer a new life form of soldiers, the Clones, that will one day blah-blah-blah-blah-blah. The good guys win, kind of, and the John Williams score still works its unearthly magic atop the screams of trumpets.

Now re-watching Attack of the Clones it’s impossible to take the narrative seriously. There are so many characters, contradictory ideas of the limits of the Force, flat lines of awfully-delivered dialogue, and so little to worry over that the outcome of the whole piece is pre-ordained; this is a prequel trilogy, after all, which we know must one day synch up with the first Star Wars movie from 1977.

The pleasure of the movie is in watching very good actors regard themselves, on-screen and mid-performance, as people who have gone slumming in this movie that, nonetheless, opened a great many doors to everyone involved. For me, the most ironically rich performance, aside from the Frank Oz-voiced CGI prosthetic called Yoda, is a three-way tie: Ewan McGregor’s Obi-Wan Kenobi, Christopher Lee’s Count Dooku, and Samuel L. Jackson’s Mace Windu. It’s as if the heroin addict from Danny Boyle’s Trainspotting (1996) really did swim through the worst toilet in Scotland to hang out with the monster from the Hammer Film’s version of Dracula (Terrence Fisher, 1958) so that Nick Fury could travel back through time from the future Marvel Cinematic Universe to void the whole problem of the Infinity Gauntlet by swinging a purple lightsaber.

–September 30, 2018