“When it comes to dying for your country, it’s better not to die at all.”

American cinematic depictions of war have run the gamut from patriotic and wide-eyed national chauvinism to harsh self-criticism over the value of conquest. There have also been considerable efforts to imagine wars and military crises in other countries, and certainly other historical periods, as much to thrill audiences with lavish sets and costumes as to shed light on little known events in far-off lands.

More unusual in the tradition of American war movies are stories sympathetic to the enemy that don’t rely on broad stereotype. Carl Laemmle, Jr. successfully ran this risk by adapting Erich Maria Remarque’s anti-war novel All Quiet on the Western Front and turning it into an award-winning drama of the highest quality.

First published in 1928 to remarkable critical and public acclaim, Remarque’s book was optioned by Universal Studios and designed as a project for one of its main directors, Lewis Milestone. From the first, Milestone worked with screenwriters George Abbott, Maxwell Anderson, and Del Andrews to fashion the novel’s portrait of German foot soldiers along the Western Front in a historically accurate way that would also be commercially viable.

A young Lew Ayres was cast in the central role of Paul Baumer, the novel’s first-person German soldier/narrator, whose experience is meant to draw us into the story of innocence lost. Appropriately enough, Paul’s journey begins with patriotic fervor and his army enlistment as a high school student. He grows older and his adventures continue through eventual disillusionment as each of his friends is killed.

In creating a visual spectacle equal to the trench battles so central to the film, Milestone employed the cinematography of Arthur Edeson and Karl Freund, along with the brisk editing of Edgar Adams, all of them put to the task of giving added life to the detailed and impressive sets of Charles D. Hall and William R. Schmidt. The resonance of the film, however, may very well stem from its special effects by Frank H. Booth who created memorable moments in his harrowing depictions of no man’s land, night raids against miles of barbed wire, and the horror of extended bombing.

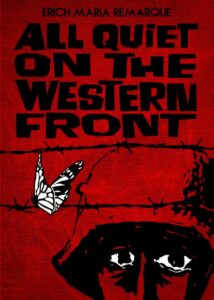

Among the film’s more remarkable moments is the contrast between the peaceful joy of Paul and his friends meeting a group of French maids and the grotesque imposition of severed hands caught on barbed wire during a skirmish. Then there are now-de rigueur plot points of war movies including a training montage, the first mission to extinguish naivety, and the conclusion where our lead is killed by a sniper’s bullet, which is made all the more poignant since Paul reaches out to touch a butterfly from the relative safety of his foxhole when he is shot.

The film attracted large audiences that made it a financial success. Critics lauded the movie as equal to the source novel, and it won the third Academy Award for what was then termed “Outstanding Production” for 1929-1930, beating out The Big House (George Hill, 193), Disraeli (Alfred E. Green, 1929), The Divorcee (Robert Z. Leonard, 1930), and The Love Parade (Ernst Lubitsch, 1929). Eventually, it was released globally, too, although members of the nascent Nazi party protested its pacifism by releasing rats in theaters and shouting counter-slogans at the screen.

In the final analysis, All Quiet on the Western Front maintains a strong connection with the present for two reasons: It holds up well as an entertainment despite a few lapses into moralizing, and it offers a humanistic story about a one-time American enemy, making it difficult to watch young Germans, played by young Americans, being ripped apart by war.

–December 31, 2017