“How very impolite of the twentieth century to wake up the children.“

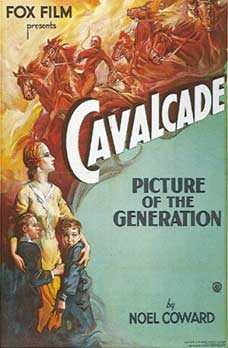

Noel Coward’s successful, London-set play “Cavalcade” (1931) was adapted for the big screen and won of the 6th Academy Award for Outstanding Production. Hailed as, “A love that suffered and rose triumphant above the crushing events of this modern age! The march of time measured by a mother’s heart!” Cavalcade is the story of two interconnected families, the upper-class Robert and Jane Marryot (Clive Brook and Diana Wynyard), who begin the story by toasting the new century on New Year’s Eve 1899 with their maid and butler, Ellen and Alfred Bridges (Una O’Connor and Herbert Mundin).

When both Robert and Alfred leave to fight in the Boer War, the cavalcade of twentieth century events begins, as the Marryot’s boys, Edward (John Warburton/Dick Henderson) and Joe (Frank Lawton/Douglas Scott), grow into adulthood alongside the Bridges girl, Fanny (Ursula Jeans/Bonita Granville). Alfred returns from South Africa, buys a bar, and dies during a drunken brawl. Edward falls in love with a childhood friend named Edith (Margaret Lindsay/Sheila MacGill), but dies on the Titanic. Joe longs for war and enlists in 1914, while Fanny turns her childhood fascination with dance and song into a career and falls in love with Joe just before he dies at the end of World War I before they marry. Meanwhile Robert and Jane remain in love and prosper, while the widowed Ellen grows older, enjoying her daughter’s career success, and their story of family life unwinding ends on New Year’s Eve 1933 with anticipation of a new conflict with Nazi Germany.

The best that can be said is that Cavalcade is a highly literate condemnation of war and needless sacrifice. When focused on intimate encounters between two or three characters, Coward’s source play, as adapted by Reginald Berkeley, balances pedantic lecturing with good vocabulary that uses two families as symbols for the fading British Empire. Cavalcade’s vignette structure therefore builds upon appealing performers asked to enliven implausible coincidence that dress up key events of the period. Such coincidence definitely encourages audience excitement, partly by showcasing the design work of William S. Darling’s crew, but when we are asked to accept that these two families closely experiences the Boer War, Queen Victoria’s funeral procession, the Titanic’s maiden voyage, World War I, zeppelin raids on London, and the armistice of 1918, it seems a bridge too far.

Curiously, one trope Cavalcade borrows from silent movies is the intertitle. Lloyd opens the movie with a few paragraphs of expository text to give us a common foundation for Coward’s upstairs/downstairs social milieu; this helpful nudge is abetted along the way of the movie’s story with further intertitles that give us the year in which things happen. This kind of audience direction is helpful, too, when a movie is as episodic (it spans 34 years of activity) and well-intentioned as this movie is (the pacifism and humanism are perfectly clearly), but it is a cinematic weakness, too; acting as an artificial means to press together dramatic events, the plot works like an essay and does not bloom based on characters behaving from depths of need and psychological complexity. This means that each character takes on a “point of view” rather than being a person, so Cavalcade is an archival imprint of what we once thought of ourselves as we were also thinking about Anglophile history.

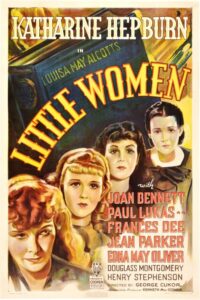

For the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences, the year’s awards competition included nine other nominated films, and three of those titles—I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang (Mervyn LeRoy, 1932), Little Women (George Cukor, 1933), and She Done Him Wrong (Lowell Sherman, 1933)—enjoy an on-going fan service.[1] Still, there were three overlooked movies that passing times have affirmed as being particularly important.

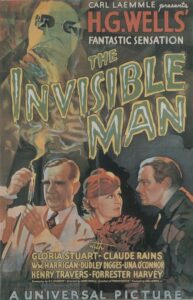

The first is King Kong (Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack, 1933), the second is the Marx Brothers vehicle, Duck Soup (Leo McCarey, 1933), and the third is the special effects masterstroke The Invisible Man (James Whale, 1933). All three movies are classics; all three appeal to modern moviegoers, and all three were written off as genre productions in the most pejorative sense of the term, meaning formulaic, low-brow, and unsophisticated. Yet each of these three movies has contributed more to the legacy of moviedom than any of the Academy’s nominated pictures from 1932-1933, based simply on the willingness of later generations to pull these dusty titles from the shelf and re-watch them.

[1] The other nominees were: State Fair (Henry King, 1933), 42nd Street (Lloyd Bacon, 1933), A Farewell to Arms (Frank Borzage, 1932), The Private Life of Henry VIII (Alexander Korda, 1933), Lady for a Day (Frank Capra, 1933), and Smilin’ Through (Sidney Franklin, 1932). Although these pictures may have ardent supporters, they have largely been forgotten by subsequent generations of moviegoers.