“Whatever you end up doing, love it.”

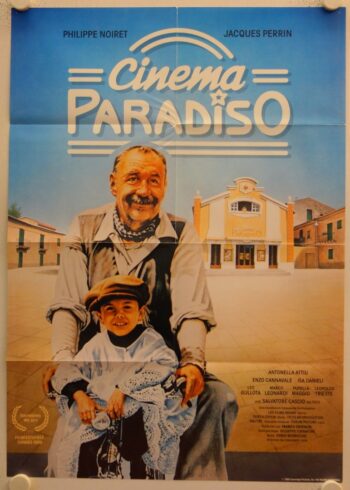

Giuseppe Tornatore’s Cinema Paradiso (1988) is simply exquisite. A film lovers valentine to other film lovers, rendered with period detail and a lavishly sentimental score by the father-son team of Ennio and Andrea Morricone, the chaptered plot expresses pivotal moments in the life of Salvatore Di Vita, played as six-year old by Salvatore Cascio, as a 16-year old by Marco Leonardi, and as a mid-40-something by Jacques Perrin. The centerpiece of Salvatore’s youthful world is the Cinema Paradiso, a theater in the center of Giancaldo, Sicily, where Salvatore wanders in search of amusement. As the son of a soldier killed in World War II, Salvatore strains his overwhelmed mother, caring as she does for him and his younger sister, and his mischief is compounded by the fact he is plainly more quick-witted and sensitive than his peers.

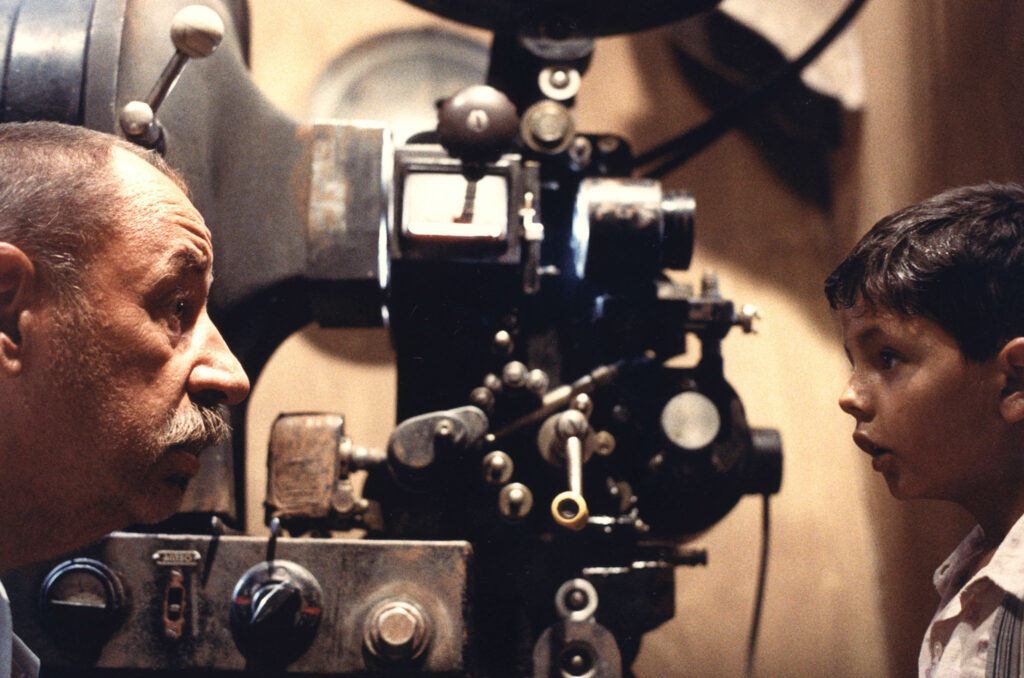

Running to and from the Catholic school and Church on the way to a very uncertain future, Salvatore finds a father figure in the Cinema Paradiso projectionist, a near illiterate man named Alfredo (Phillippe Noiret).

Together, this puckish cherub and bearded curmudgeon entertain the townsfolk with imported movies and the post-War melodramas that up-and-coming filmmakers would soon rebel against. Then the theater burns down, blinding Alfredo and elevating Salvatore to projectionist when a lottery winner chooses to rebuild the theater.

As a teen projectionist, Salvatore finds love but worries over how to attract Elena (Agnese Nano), the daughter of a leading local bureaucrat. With a handsome smile and great persistence, he slowly enters her good graces over the objections of her family who, when he leaves town for compulsory military service, disappear without a forwarding address.

Salvatore returns from the army, heartbroken, and Alfredo warns him off from staying in Giancaldo, or even of coming back again once he leaves. Striking out on his own is the best choice, Alfredo tells Salvatore, and the young man sets his sights on Rome where he eventually makes his mark as a filmmaker before returning to Sicily, 30 years after his departure, for Alfredo’s funeral.

Much of the action takes place in straight forward fashion, save for the opening scenes of middle-aged Salvatore returning home late one night to receive news that Alfredo is dead. From that point onward, the film’s narrative uses the Perrin-acted sections as interstitial material to bind together the three segments of Salvatore’s life, his boyhood, adolescence, and middle age. In this way Cinema Paradiso is Tornatore’s meditation on small town life in Sicily, but really in parts all over the world, where children sometimes grow up under the shadow of ended wars. Whether fatherless, like Salvatore, or driven mad and left impoverished, as is the case of other residents in Giancaldo, the passage of time forces small town people to adjust old customs into a new world of changing opportunities.

For instance, Catholicism looms over Salvatore’s young life. As an altar boy, Salvatore also attends Catholic school and in one early comic scene we watch him spy on Father Adelfio (Leopoldo Trieste), who makes a weekly pilgrimage to the Cinema Paradiso where he gives Alfredo instructions about what shots are objectionable and need to be cut before any public performance.

Dutifully, Alfredo makes the required cuts, despite his own preferences, and fills a giant trash bin of celluloid strips. When the townsfolk finally see the butchered result, they are frustrated since no one has ever seen an on-screen kiss, and this much despite the fact that we know how the theater is a multi-purpose building, used variously as a brothel, living room, movie theater, restaurant, and hunting ground for romance, depending on whoever is present.

This vignette on censorship is characteristic of how Tornatore beautifully inscribes the mid-20th century struggle to manage the competing influences of commerce and entertainment, on one hand, with the high-minded ideals of art and beauty on the other. In doctrinaire Catholic fashion, Adelfio’s hand of temperance defies both commerce and art, making many of the movies Alfredo screens into a mincemeat of nonsense in an era, the 1950s through the mid-1960s, that’s partly defined by the birth of Neorealism, a movement devoted to everyday truths, however upsetting, banal, and uncooked.

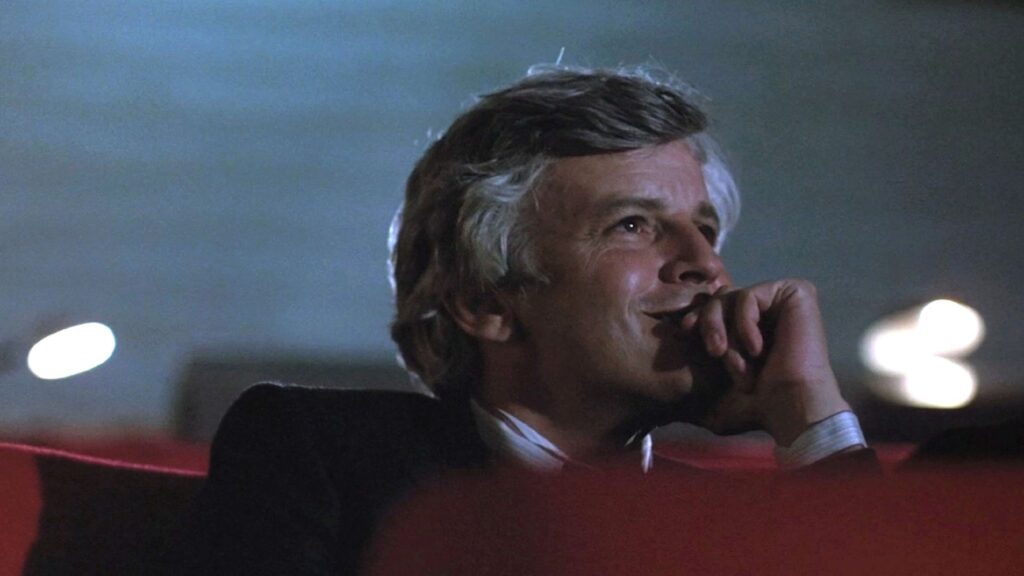

The conclusion of Cinema Paradiso is where all this attention to detail, particularly of how and where movies are enjoyed by everyday people, is wedded to what could be, in lesser hands, sheer sentimental pabulum. Sitting in his Rome screening room with a mystery reel as bequest from Alfredo’s estate, silver-haired Salvatore asks his projectionist to thread the film strip and waits for the house lights to dim. On-screen he’s greeted by all the kissing scenes Alfredo was forced to remove, which have been assembled by a blind man gifted with knowing how a mechanical object called a movie projector will shoot light through chemically bathed plastic strips in the production of “the movies.” Salvatore lowers in his seat and his eyes moisten. He sees all that we see, those love affairs and romantic picadilloes that were once objects of fear in the Church, which have become the stock and trade of Salvatore’s life, here turned into the final gift of a dead man for his son.

It’s a wonderful conclusion focused on a father-son bond that isn’t deformed through contests of strength. Here, a man loves a boy who is not his flesh and blood, and that boy loves the man who once told him to run away and become himself. In the end, we see that each man spent his life in love with the other, and that love is expressed through bright images projected onto the walls of a comfortable theater.

–September 30, 2019