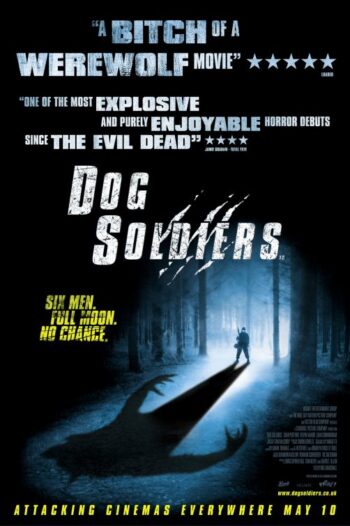

Dog Soldiers was released in the United Kingdom in 2002. It gathered mixed reviews and devoted fans but failed, despite its high action content, to pick up an international theatrical distributor. Subsequently released on home video, courtesy of Artisan Entertainment, Dog Soldiers has been well received among cinephiles and writers, this author included, for whom its Grand Guignol spectacle and numerous external references are the focus of healthy fascination.

Between eviscerations and gunshots, then, the Dog Soldiers intertext depends on numerous visual icons and set pieces borrowed from other productions. Thus, the film’s endless fascination with pop culture detritus excites viewers already giddy at the appearance of squib effects and howling werewolves.

Which is to say, Dog Soldiers borrows freely from other movies and fairy tales. Yet it’s produced with such infectious brio that it suspends consideration of these precedents and becomes a singular artifact. Whether this amounts to empty pastiche, theft, innovate collage, or mindless entertainment is precisely the question under investigation.

Part I: of Lycanthropes and Warriors

Centered on a British army platoon in the Scottish highlands, Dog Soldiers begins with one back-story, as a couple camps in the highlands one month previous to the main action and exchange a silver dagger before hungry werewolves kill them en flagrante delecto. In the other back-story, that same night, a special operations exercise to initiate a new recruit, Private Cooper (Kevin McKidd), goes awry when he refuses an order from his commander, Captain Ryan (Liam Cunningham), and is demoted to a regular army unit.

Cut to the next full moon one month later. Cooper’s new platoon is dropped, via helicopter, into the highlands for an exercise intended to hone Ryan’s team. Their assignment: exploit a seam in Ryan’s position. The complication: special operations are a sadistic bunch, meaning anyone captured will face a beating.

Leading Cooper’s platoon is Sergeant Wells (Sean Pertwee), a veteran of the first Gulf War. He plans to hike through the highlands and avoid Ryan completely. Unbeknownst to him, however, the exercise is intended to funnel his platoon at Ryan lying in ambush.

During a campfire idle, and unaware of the trap looming before them while telling stories of military life and a missed football match between Germany and England, a mutilated cow falls from a cliff above them. Shocked and scared, Wells’s platoon members see a flare in the sky and so spend a tense evening, waiting for first light to investigate.

The next morning, they discover the remains of Ryan’s team in puddles of blood and guts spread across a sandbag bunker. Unsure what’s befallen their would-be foe, the platoon is surprised when Ryan rears up from beneath a pile of ammunition, badly mauled and nearly dead, demanding he be removed to safety.

Howls are heard in the dusky light and with their radios failing the platoon begins moving through a forest as fast-moving shapes assault them. One soldier becomes a werewolf’s dinner and Wells is disemboweled fighting off a vicious attack.

Running towards a service road where headlights approach, the platoon commandeers a Land Rover. Inside sits Megan (Emma Cleasby), a highlands zoologist, who’s come to investigate the gunfire she’s heard. Unsure what else to do, she persuades the platoon’s survivors to visit the home of some people she knows in the forest. Once there, she reasons, they’ll find safety and warmth, and they can plan their next move.

Naturally, the house is empty, lacks a phone, and as the survivors set up a perimeter, their vehicle is destroyed by the werewolf pack. Attack after attack is then repelled, each time punctuated by further casualties and a growing sense of hopelessness, save for Cooper who is singularly calm about his survival.

Ryan, who was once near death, magically recovers from his injuries and reveals how his team was trying to capture a werewolf for weapons research. Using Wells’s platoon as bait to attract these “manimals”, Ryan’s team was quickly overwhelmed. As a consequence, he presently transforms into another hairy beast and attacks his one-time allies until he’s forced to leap out a window and join his new four-legged clan.

Because Wells has been mauled, and because he’s also speedily recovering from his injuries, Cooper takes control of the platoon. Megan suggests they hotwire a car stored in the farm’s barn but when the effort fails, she explains she’s actually another lycanthrope, but one tired of living among such a dysfunctional family. Having earlier hoped for deliverance from her sad condition by Cooper’s platoon, she’s instead let the werewolves into the farmhouse.

Immediately shot through the forehead in the midst of her transformation, Megan falls, as do the remaining platoon members, save Cooper and Wells who fight through a series of standoffs. In the first, they lock themselves in a bathroom and carve their way through a wall into an adjacent bedroom. There, they lock themselves in a wardrobe and shoot their way through the floor, landing in the kitchen.

Wells, recognizing he’s about to turn wolf, pushes Cooper into the farmhouse basement and opens gas valves to blow everything up. Underground, Cooper confronts Ryan in wolf form, along with the leavings of the werewolf clan’s victims, including the campers’ silver dagger. The two fight until Cooper thrusts the dagger into Ryan’s chest, killing him, as Wells ignites the house in an inferno, thereby making Cooper the lone survivor.

Part II: Reference or Theft?

Childhood fairy tales instruct us as to our preferred moral framework. These same tales serve as common ground, educating citizens and informing our opinions on all matter of life from the weather to fashion. Fairy tales also impose archetypes and inspire our assimilation into civilized society.

Movies exhibit our cultural fantasies through capital- and technologically-intensive means. They have long been an entertainment staple, supplying us with the vocabulary of cultural exchange. But movies also impose archetypes through the spectacle of narrative, which includes seamless stories, condensed space and time, and denouement.

For a film like Dog Soldiers, combining as it does several fairy tales and other movies to heighten its impact, intertextuality isn’t a matter of simple homage. Instead, it’s important to consider the degree to which Marshall, as writer-director-editor, uses three fairy tales to organize his film’s plot while pointing to numerous popular movies, both to draw our attention to these other movies but also to more exactly help us appreciate the predicament of his stranded platoon.

Skillfully combining these disparate elements with both flair and self-conscious humor, Marshall interlays these well-known semantic joins across our knowledge of constituent parts. That we understand these references attests to our media savvy. That Marshall so capitalizes on us demonstrates his turning away from the usual aspiration of originality and moves towards a creative strategy based on reproduction and combination.

Meaning Dog Soldiers is plotted against Little Red Riding Hood, Goldilocks and the Three Bears, and the Three Little Pigs and the Big Bad Wolf. It opens, less two back-stories, with a British platoon rooting around Scotland, trying, like Little Red Riding Hood, to find their way to the symbolic grandmother’s house, or seam through Ryan’s position. Soon afterwards, they pick up Ryan before being picked up by Megan who deposits them, like unknowing Goldilocks, at the doorstep of the bears’ house, or the werewolves’ home. Once inside, they are besieged by the Big Bad Wolf, here transformed into a family of werewolves, just like the Three Little Pigs, but it is to the brick building pig, aka Cooper, for whom the moral fable of always being prepared finally rings true.

Combining these three fairy-tales, Marshall also explicitly references The Evil Dead, since one of the platoon’s members is named Bruce Campbell, and Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, when the platoon talks of the impossible choice of the Kobayashi Maru training exercise. Sprinkled in for good measure is a visual and editorial tone consistent with the Deadseries by George Romero, not to mention borrowed techniques from An American Werewolf in London, The Howling and Wolfen, including fast-moving, first person, point-of-view shots, sophisticated make up effects, echoing howls, and close-up shots of fangs and claws doing their work.

Viewers will also notice the lifted table transformation of Dr. Jeckyl and Mr. Hyde during Ryan’s sudden lyncanthropic turn, not to overlook the too casually ajar doors and windows that preface attacks, as in virtually every slasher movie, but especially the Friday the 13th series. Bullet time from The Matrix appears, along with hallway tracking shots suggesting the steadicam work in The Shining. Then there are werewolves turning doorknobs to enter the farmhouse, like The Thingwhen the alien attempts to access the arctic observation post, and there is the listed plot sequence of shooting holes in a floor, as seen in Escape from New York and Judge Dredd.

To a lesser extent, war movies also play a role in the film. Among them, Platoon and Full Metal Jacket loom large, considering the small talk and gossip of the soldiers, but equally because of the gritty look and feel of cast members mimicking military strategy and procedure while carrying appropriate equipment and speaking appropriate slang.

The farthest-reaching fun of Dog Soldiers, though, is in recognizing the other movies that structure the newer film’s tightly drawn plot. Obviously, Aliens and the group of marines sent to investigate a lost colony is the organizational basis of Wells’s platoon, and so is Predator, as in the gradual attrition of a group of soldiers by an unstoppable killing force. Then Straw Dogs, Assault on Precinct 13, and Zulu play a role in the farmhouse stand-off with its waves of attacking baddies repelled by desperate heroes.

In the end, Dog Soldiers has a familiar plot and hits all the marks on the way to its cathartic conclusion. Seasoned viewers will notice references to dozens of other movies and fairy tales, which further appeals to those who admire cultural bricolage. Yet there are also viewers equally disgusted by a lack of concern with original story-telling strategies or innovative technique. For them, the offered pleasures of sifting through layers of intertext for occasional gems of peculiarity prove inadequate. The divide between these two viewpoints is wide, and in each position exists the standard divide between hi- and low-culture, or the unique masterpiece versus lesser reproductions.

Regardless, Dog Soldiers successfully enlivens its central platoon. Although rendered as types, but enacted with three-dimensional panache, each soldier relates to other pop culture characters caught in similar circumstances. Herein is a key to Marshall’s mosaic. For in the act of knowing their fictional position within a by-the-numbers action scenario, Cooper’s platoon moves effortlessly from meta-commentary to the minutiae of surviving a single full moon and this much is the lasting grace of Dog Soldiers.

It gathers intensity from easy comparison to its many references, allowing Dog Soldiers to turn from being a laughable hodgepodge into a nuanced mélange, or combination, of well-known movie tropes. In so doing, it becomes the epitome of a great genre picture.

–May 31, 2018