“I’ve seen this neighborhood change from pastures to the hellhole it is now! “

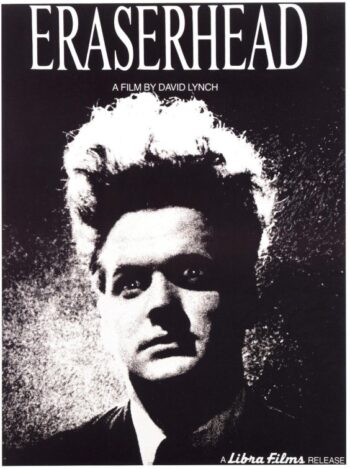

From The Elephant Man (1980), his most mainstream movie, through Blue Velvet (1986), his most celebrated film, with less-known works like Wild at Heart (1990), The Straight Story (1999), and Inland Empire (2006); and from the studio flop Dune (1984) through a foray into television, Twin Peaks (1990-1991, 2017), I find David Lynch’s work difficult to enjoy. Nonetheless, I’ve met many Lynchians over the years, and I am aware that Eraserhead (1977) is the anchor of his career, not only because it was his feature debut, but because it is over-filled with material, textures, moods, and incongruities we now freely call his artistic “stamp.”

A cult film of the highest order, Eraserhead is unpleasant, surreal, slow moving, and repulsive in its presentation of a nightmare world of belching smokestacks and clacking machines. Henry Spencer (Jack Nance) is the lead character in this landscape of barren despair and the “action” takes shape from the fact that his girlfriend, Mary X (Charlotte Stewart), gives birth to their monster-child that squeals and inflicts discomfort on everyone in ear shot.

Meanwhile Henry fantasizes about the Beautiful Girl Across the Hall (Judith Anna Roberts), toils at a non-descript job, and listens to the singing Lady in the Radiator (Laurel Near), a literal description of what and who she is, while dreaming of heaven, anywhere but here. His world is filled with inorganic objects that become animated and possessed of wish fulfillment fantasies and a variety of sexual hang-ups that frighten Henry even while exciting him.

Because the plot isn’t really all that important due to its general inscrutability, and because Eraserhead stands up or falls on its twisted images and “gooey” sounds (oh, those pencils—and what is the Beautiful Girl Across the Hall crushing under her feet?), it’s to the extra-text—the events and reactions to the film—that most interest me with the passage of time.

So it begins that David Lynch, then a student at the American Film Institute, embraced the zeitgeist-y goal of creating a more personal cinema. After drafting a 20-page long script, he fought with AFI to provide financial assistance for the film he eventually produced, edited, wrote, directed, and co-scored with a reported budget of $10,000 that took five years to complete due to a dependence on locations where sets were erected, taken down, and re-erected, over and over again, to make room for other work.

Exhibited with the tagline, “In Heaven Everything Is Fine,” Eraserhead was immediately associated with, and written off as being, just another disposable B-movie. Then it became a midnight favorite in mostly urban theaters where unusual fare can sometimes find a devoted audience. Playing this way for months, and sometimes years, Eraserhead established Lynch as a movie town legend during the period when Hollywood was being radically reformed by the blockbuster, post-Jaws (Steven Spielberg, 1975).

Just as the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences awarded Annie Hall (Woody Allen, 1977) its top honor for Best Picture of the year, and as Star Wars (George Lucas, 1977) burned up the box office with a fantasy about wish fulfillment and traditional heroes, Eraserhead turned such escapist gratification on end. Eschewing a plot-driven narrative with sympathetic, attractive characters while relying on an aesthetics born from a poverty row budget and “raw” production circumstance, the film inflicts a response onto its viewer rather than inviting any kind of identification, and it’s this emphasis that sets it apart from the mainstream, then and now.

I recently showed Eraserhead to an audience of undergraduates after first showing them The Elephant Man and The Straight Story. I wanted to emphasize the importance of creative license, individual vision, the possibility of pursuing something other than CGI car chases and choreographed knife fights, and I wanted them to examine Lynch’s work in reverse chronological order all the back to his origin story about a man trapped in a nighmare. By the time the class was over with, when my students had endured four months of my digressions and good intentions, Eraserhead clearly proved to be a headscratcher; several students notably left in the middle of the screening and failed to complete the course.One thoughtful student, who often stayed after class to ask questions, summed up the experience well. He said, “I won’t forget this one, but I’m glad it’s over.”

–December 31, 2017