“There’s more to life than a little money, you know. Don’tcha know that?”

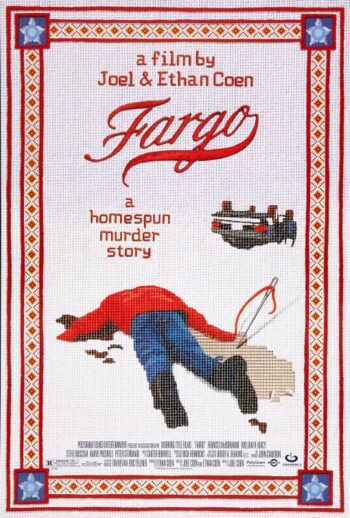

The Joel Coen-directed Fargo (1996) is the story of a sad sack named Jerry Lundegaard (William H. Macy). He’s a husband and father, and he works at an Oldsmobile dealership where he’s leveraged the value of cars he doesn’t own with a bank that’s ready to foreclose. Scheming is way through, Jerry hires two dim-witted criminals, Carl Showalter (Steve Buscemi) and Gaear Grimsrud (Peter Stormare), and asks them to kidnap his wife in order to ransom money from his wealthy father-in-law. Things go wrong when Carl can’t control Gaear, and that’s when a small-town police chief named Marge Gunderson (Frances McDormand) begins trailing the duo, finally rolling up the whole caper that leads back to Jerry.

In this version of the story, which I acknowledge is outside the mainstream sum, Carl, Gaear, and Marge are all secondary to Jerry, along with every other bit player on-screen. The memorable part of Marge, played really well by McDormand, isn’t the lever of story; she is only a foil to Jerry’s idiocy, in every way superior to his poor judgment and incapability to fathom evil. His decisions make everything else about Fargo possible. Thus, Jerry is our (anti-)hero and his failure to achieve his goals is roughly equivalent to the movie’s poor aftertaste.

Fargo takes place in the winter of 1987 in snow country spread among various locales in Minnesota and North Dakota. The people we visit are largely white, middle class, dependent on owning a good car or truck, and wholly devoted to surface courtesies in the way the Midwest has long been reputed (particularly after being satirized by this movie). Everyone is open and smiling, but no one is telling the truth. Only Marge is hip to these registers of performance, and it’s to her small scenes of domestic life that my memory lingers because she is seven months pregnant and swollen, and her husband is a simple man with whom she cuddles up nightly.

This small note of comfort catches my attention because so much else of Fargo is unforgiving, much like a Minnesota winter. The thing is, Fargo is beloved and discussed as the lynchpin of indie cinema, circa 1996, although I can’t help but think that it’s deeply over-rated, not due to some technical malady, but because it’s cruel.

Having seen Fargo with a clean separation of more than 20 years between screenings, I can report that I did not then, and do not now, like it very much. Yes, there are impressive vignettes because the Coen Brothers, Joel and his younger brother Ethan, write character quirk with the best of our novelists and journalists. Yes, there are catchphrases that passed, seemingly instantly, into the popular culture of the middle 1990s and remain a signpost to that time. Yes, there is something eerily fascinating with the movie’s criminal ineptitude and procedural investigation, all buried under voluminous winter coats. Yes, certain images really stick out, like foot prints in the snow or a useful wood chipper.

But it’s the slippery quality of the Coens’s world view that I stumble over because Fargo casts our lot with Jerry. When his scheme falls apart, we don’t re-align our interests with Marge; we remain outside her simple life, recognizing how she exists in this story to clean up the messes of foolish men because she is, literally, the embodiment of maternal fecundity and steadfast responsibility, complete with morning sickness and a tricky smile.

–November 30, 2018