“Of course, they’ll want to use it as a weapon. Bombs versus bombs, missiles versus missiles, and now a new superweapon to throw upon us all!”

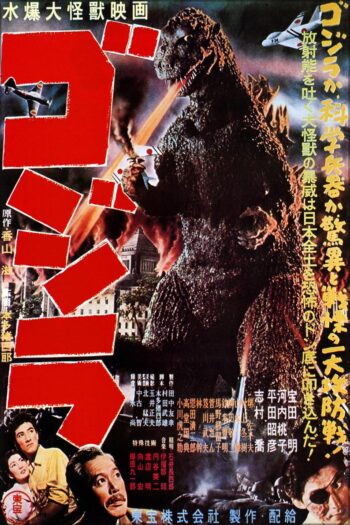

Ishirō Honda’s Godzilla (1954) is the most self-reflective civilizational account of disaster ever made. After more than 30 franchise movies about the eponymous creature, made mostly in Japan and through licensing agreements in the United States, and after developing uncountable ancillary markets including video games and children’s toys, Godzilla is no longer freighted with the same meaning as in the middle-1950s. This massification of the title “hero” demonstrates the underlying IPs’ commercial value, but it in no way lessens the impact of this very strange, very well-made horror movie about technology run amuck.

The historical backdrop begins with the Empire of Japan, established in 1868. Through conquering parts of mainland Asia, most notably in China, Russia, and Korea, the Empire expanded its territorial holdings and sought power on a world stage, ultimately forming an alliance with Germany and Italy that directly led to the conflagration we now abbreviate as World War II. Bloodshed followed on a vast scale and in 1945 the Empire surrendered after two atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, a premonition of Armageddon.

Nine years later, a resurgent economy, partly the result of American occupation and subsequent reformation of the Japanese government, created an efflorescence in the arts, particularly in the cinema. Honda’s movie is a product of this context, and in it we learn about developing hope for the future in a place literally scarred by the nuclear age.

The story concerns hydrogen bomb testing that upsets an ancient, hibernating creature that local people call “Godzilla.” When the creature awakens in the ocean depths and makes landfall, it destroys everything in its path and cannot be stopped by conventional weapons. Figuring out whether to preserve the ancient creature or destroy it by any means necessary, the plot of the movie turns to a love triangle between a salvage ship captain, Ogata (Akira Takarada), the woman he loves, Emiko (Momoko Kōchi), and the scientist, Serizawa (Akihiko Hirata), to whom Emiko was once pledged in an unconsummated arranged marriage.

Serizawa invents a weapon called “Oxygen Destroyer,” which rots an organic creature by degrading its oxygen atoms. After much argument, Serizawa agrees to go with Ogata into Godzilla’s ocean lair and release the “Oxygen Destroyer.” In the event, Serizawa forces Ogata to the surface, releases his weapon, and dies a martyr for his nation and for the loving memory of Emiko, as he and the monster dissolve into nothing.

For the mid-1950s, Godzilla deploys startlingly good special effects, including miniatures, optical effects, superimpositions, composited images, and the precedent setting value of two men, Haruo Nakajima and Katsumi Tezuka, fitted into a full-sized latex suit. But the ultimate signature of Godzilla, more so than even its value as a symbol of national threat concluding World War II, is the impact of composer Akira Ifukube’s Godzilla roar.

As reported by NPR[1], Ifukube coated a leather glove in pine-tar resin to create friction and then rubbed the glove against a double bass. The resulting sound calls across decades to the faithful who celebrate a fire-breathing, city-stomping monster that once symbolized abject Japanese defeat but is now regularly feted as the savior of Earth.

–November 30, 2018

[1] https://www.npr.org/2014/05/18/312839612/whats-in-a-roar-crafting-godzillas-iconic-sound