“All this child needs is some food.”

It’s not often that children star in movies. When they do, they often succeed; they almost never die.

In Isao Takahata’s Grave of the Fireflies (1988) these rules are upended in the adaptation of a short story called “Grave of the Fireflies,” written by Akiyuki Nosaka and published in 1967. Nosaka’s story is a semi-autobiographical account of how some Japanese civilians survived World War II, or else they died.

The stakes of bringing this difficult story to life were then amplified by Takahata’s decision to make an animated feature that opens with the story’s end. “September 21, 1945. That was the night I died,” says a teenage boy named Seita (Tsutomu Tatsumi), whose body lies still on a subway platform. From there we move back to early 1945 when Kobe, Japan was firebombed in an effort to conclude the Second World War.

Our point-of-view character is Seita, who cares for his younger sister Setsuko (Ayano Shiraishi). During a bombing raid, they leave home separately from their mother, who is killed, and the children seek shelter with a distant aunt who provides for them until war privation forces them apart.

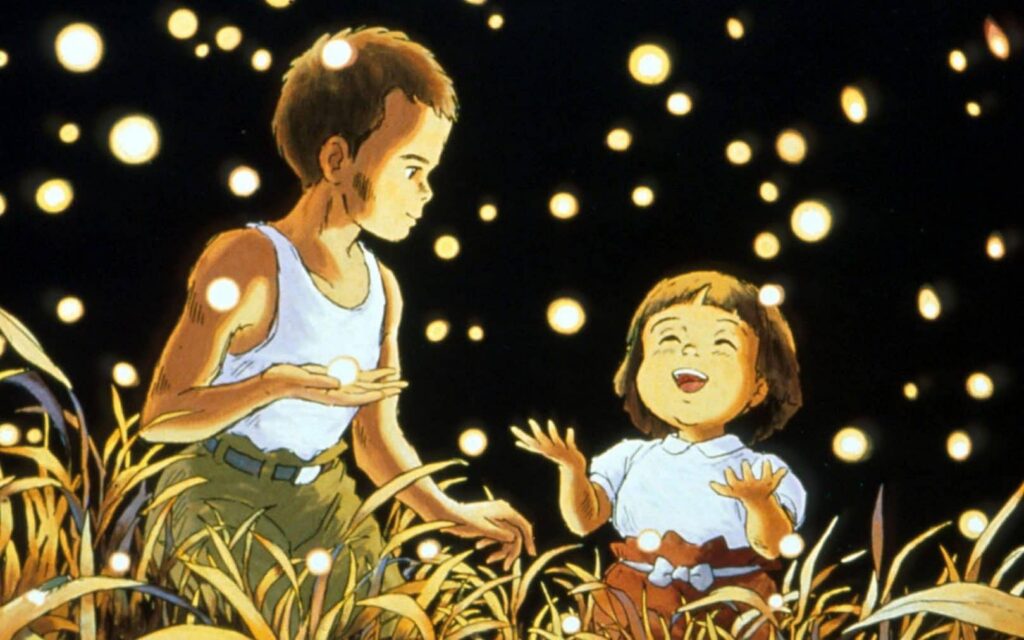

Seita and Setsuko move on into an abandoned bomb shelter, where they joyfully set up a new “home” and begin starving to death. Desperate, Seita begins stealing food while Setsuko dwindles and dies from malnutrition. Seita cremates Setsuko and ends up dying among other poor souls on a subway platform.

Writing that war is sad is obvious. When that sadness is attached to particular people behaving in specific circumstances, a vague idea can turn into something vivid.

Grave of the Fireflies depicts how two children die from what General Sherman legitimized in “total war,” meaning complete offensive conduct against both military and civilian personnel. Using colorful cell animation, periodic bursts of extraordinarily hand-drawn natural imagery, and precisely connected sound recordings, Grave documents how the suffering of war looks and feels, even after the shooting is ended.

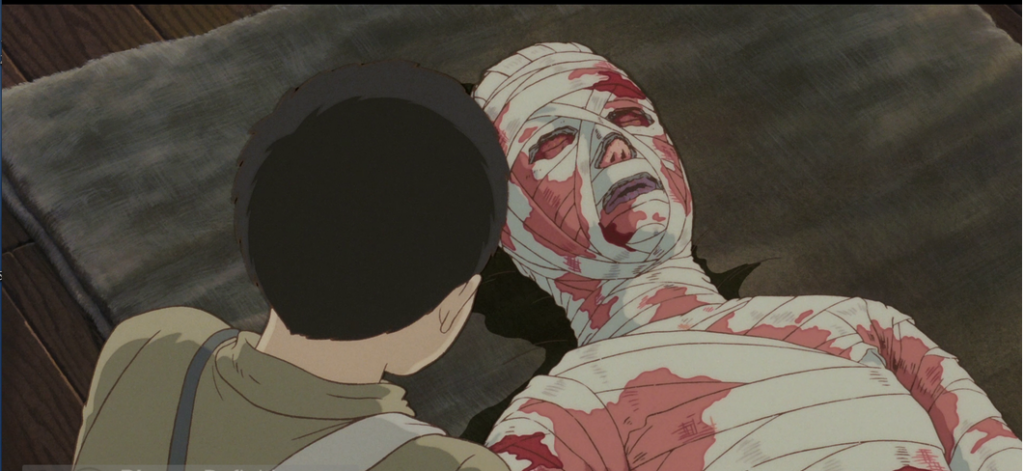

Perhaps the most striking thing is the way bodily harm appears on-screen. When the initial bombing raid on Kobe ends, we see torched bodies and visit a hospital where Seita and Setsuko’s mother, wrapped in bloody bandages, expires. Later on, we see Setsuko’s body covered in itchy sores.

It’s telling that a middle aged Japanese artist named Takahata, who was 52 at the time, would re-consider the definitive conflict of his nation’s history and offer one of the most distinctive stories of war through an animated feature released through Studio Ghibli, known as the home of uplifting fantasists like Hiyao Miyazaki. War is sad, true, but in the hands of a master, it can be unexpectedly heart-breaking, too.

–September 30, 2019