“I met this six-year-old child with this blank, pale, emotionless face, and the blackest eyes, the Devil’s eyes. I spent eight years trying to reach him, and then another seven trying to keep him locked up.”

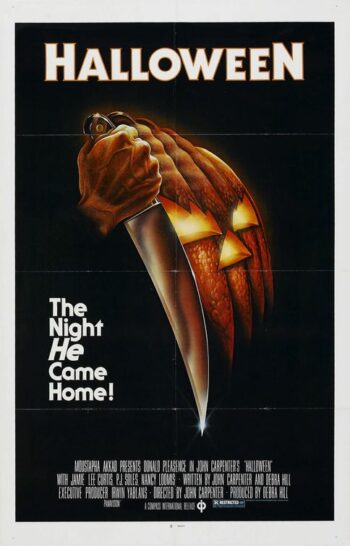

Re-watching John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978) after many years is to be reminded of changing movie-making technologies and the nature of our accelerated culture. Newer movies now explore graphic violence with stunning visual and aural commitment, and newer audiences don’t always have patience for still shots or quiet interludes. In the main I have adjusted to suit the changing culture and its close-up SFX shots of arterial spray, but I’m also old enough to appreciate what a departure Halloween truly is and was.

The story centers on Laurie Strode (Jamie Lee Curtis), a nerdy high schooler, who babysits her way through Halloween, 1978, while her two closest friends try to have sex. Fifteen years before, in 1963, a then six-year-old Michael Myers (Wil Sandin) saw his sister have sex with her boyfriend, and he killed her. Since that time, he has matured into a mute psychiatric patient (Nick Castle) under the care of Dr. Sam Loomis (Donald Pleasence), and he’s broken out of the facility to re-enact the crimes of yore. Of course, he’s successful, but he doesn’t kill Laurie or Loomis, who both survive to star in some of this movie’s many sequels.

Technically, Halloween is a clinic in using long takes to portray menace. Action spreads across a widescreen that allows everyday suburban objects to loom as threatening. Hedge rows may beautify a yard, true, but they also hide possibility in shadows that are impenetrable.

That widescreen rectangle goes indoors, too, where two-story houses turn into nightmare. Dark hallways contrast with lamplight, and the moon streams through picture windows to setup jump scares, although most of the horror is in wondering where Michael will next appear. And appear he does, usually with a brief reflection of his face on a window pane.

As the prototypical slasher movie, the body count in Halloween is low with only five kills: one in 1963 to set up the backstory, and four in the present, of which we participate in three because the fourth is revealed after the fact. Yet Michael is superhuman and lacking any basic psychology to explain his behavior. Loomis simply calls him “evil,” meaning he can absorb a knitting needle to the neck, a wire to the eye, a butcher’s knife to the torso, and six rounds from a revolver before falling backwards from a second story balcony, only to disappear among end credits to spawn a new style of horror movie villain.

While cinephiles can easily see how Halloween respond to the likes of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (Tobe Hooper, 1974) and Psycho (Alfred Hitchcock, 1960), the lasting shock of the movie is that things that go bump in the night are sometimes really dangerous.

For a tour-de-force on screen frights, though, watch the first several minutes that feature an unbroken first-person shot from 6-year-old Michael’s point-of-view. We become him with his scattered breathing and excitement in the prowl. When his sister ascends to her bedroom with her boyfriend, we round the house, enter through the back door, find a knife, climb the stairs, pick up a mask, find her, and stab her to death before going back down the stairs where we are greeted, and seen for the first time, in reverse shot: we are really only a boy in a clown suit. It’s a stunning open that has become the cultural legacy of this unexpected super hit that was inducted in the National Film Registry in 2006.

–October 31, 2018