“There’s always work at the post office.”

When Key & Peele left the air in 2015 after a four-season run, there were arguments in some circles about whether it was a cleaned-up version of Chappelle’s Show (2003-2006). Partisans were quick to point out the “friendlier” nature of Jordan Peele and Keegan-Michael Key, each of whom presents a gentler presence than Dave Chappelle whose persona is more profane, indeed more “black.”

Arguments about showbiz lineage sometimes developed from the comparison of Chappelle versus Key and Peele, to included Mad TV (1995-2009), where Key and Peele met, and In Living Color (1990-1994), created by Keenen Ivory Wayans and formed around him and his siblings, Damon, Kim, Shawn, and Marlon, along with future stars like Jim Carrey and Jamie Foxx. Like standout sketches in both Chappelle’s Show and Key & Peele, the popularity of In Living Color was built around self-aware Black performers, and their allies, who ridiculed then-conventional portrayals of how Black people looked and sounded in mainstream TV and movies. Some audiences were turned on; many were offended. The upside is that a group of Wayans-led Black performers increased the number of non-White faces in mass entertainment.

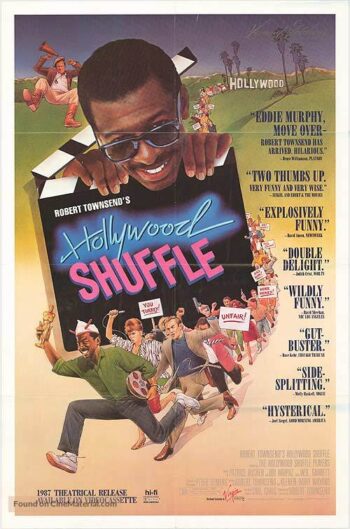

Importantly, the template for both TV shows is the Robert Townsend feature film Hollywood Shuffle, which debuted on 15 screens on March 20, 1987, which was co-written by Keenan Ivory Wayans who plays several supporting on-screen roles. Hollywood Shuffle opened well behind Richard Donner’s race-conscious cop adventure Lethal Weapon(1987), and it was a tour-de-personality directed, co-written, co-produced by, and starring Robert Townsend who plays Bobby Taylor, a young Black Los Angeles actor who dreams of becoming a Hollywood star.

Bobby endures the racism of casting agents, and he’s constantly harassed by thoughts of failure. He works at a fast food restaurant, Winky Dinky Dog, and enjoys the support of his girlfriend Lydia (Anne-Marie Johnson), while being buttressed by his Grandmother (Helen Martin) and enjoying the hero worship of his younger brother, Stevie (Craigus R. Johnson).

After Bobby gets a “dream” part in a Blaxploitation actioner called Jivetime Jimmy’s Revenge, he is unable to humiliate himself in racist caricature, and so he quits. The movie abruptly ends with Bobby playing the spokesman for a US Post Office ad, the one place where his Grandmother told him he could always find honest work.

Moving quickly through this coming-of-age premise, Hollywood Shuffle acknowledges the painful experience of never seeing “someone like me” in screened entertainment and moves to correct the issue. The method for this correction, played on-screen in satirical shorts, is Bobby’s fantasy life of what might be possible if he were somehow in control of “the movies,” just as Townsend is in control of Hollywood Shuffle.

Perhaps the most impressive single skit is an ad for “Black Acting School,” wherein Bobby, sporting a posh British accent, exhorts his assumed-to-be Black audience to call now and learn how to behave Black from a series of White instructors. It’s delicious fun, made more so by the fact that each of the stereotypes outlined in the movie match-up with the analysis provided by Donald Bogle in his 1973 academic study Toms, Coons, Mulattoes, Mammies and Bucks: An Interpretative History of Blacks in Films.

A bit later on Bobby imagines himself in a Siskel and Ebert-like program called Sneakin’ in the Movies, in which two theater hoppers give their thumbs up or down on several featured titles. What follows is very on-the-nose satire of four movies known to be demographically attached to certain moviegoers while alienating others, including Amadeus Meets Salieri, Chicago Jones and the Temple of Doom, Dirty Larry, and Attack of the Street Pimps. Of course, it helps if a person is already aware of Miloš Forman’s Amadeus (1984), the Indiana Jones series, Dirty Harry (Don Siegel, 1971), and zombie movies, generally, as typified by George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968), but the snippets on view are hilarious.

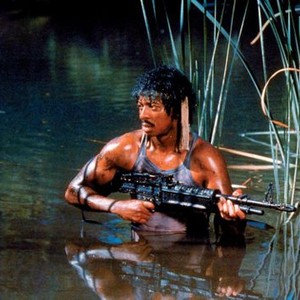

From there Bobby’s success materializes with the lead part of Jivetime Jimmy. To celebrate his opportunity, he treats Lydia to dinner and the pair fall asleep after watching a movie of the week on TV. Then Bobby imagines himself as the star of a noir film called Death of a Breakdancer before dreaming of becoming a five-time Oscar winner in such celebrated roles as a Black Super-man, a Shakespearean lead, and the campy remix Rambro.

On set, when Bobby sees his brother’s disappointment with his performance on Jivetime Jimmy’s Revenge, the “chewy” stakes of Hollywood Shuffle become apparent. Starved of opportunity, non-mainstream performers seek any work to make it big. Yet the sacrifice required for success is, as Bobby realizes, not always worth the cost of losing personal dignity and failing to offer a good role model for Stevie.

It’s a hard lesson made all the more remarkable because Townsend and his production staff managed to produce Hollywood Shuffle for a trifle of average costs in the middle 1980s. Against a small investment, usually reported as $100,000, the movie grossed in the millions, forcing entertainment leaders to recognize the potential of untapped audiences.

That the energy for exploring culturally sensitive material was designated “comic” rather than “dramatic” is how Keenan Ivory Wayans convinced executives at 20th Century Fox to take a leap of faith on In Living Color. That the fan base for Hollywood Shuffle embraced the program and lent support to it and such future programs as Chappelle’s Show and Key & Peele is obvious, and the complete way to see Robert Townsend’s legacy.

–August 31, 2019