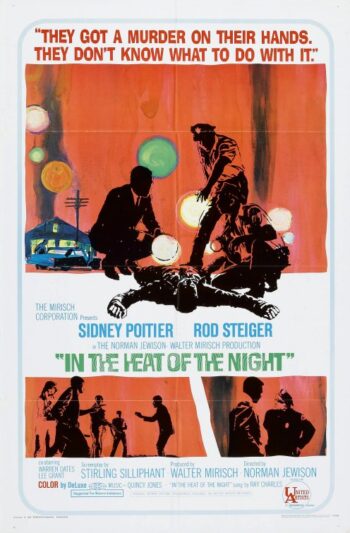

Take 1: In the Heat of the Night spends time looking at a racist lawn jockey, considers the value of non-medical abortion, and holds court for Sidney Poitier’s, “They call me Mr. Tibbs.” It’s an Oscar winner that does its job, one tidy sequence of great screen acting after another.

Take 2: To understand how and why In the Heat of the Night won Best Picture it’s important to remember the place of Black Americans inside, as well as outside, the social mainstream in 1967. It’s likewise necessary to remember Sidney Poitier’s position within this moment as being more important than any other actor in any given film with which he was associated. Taken in the larger context of Civil Rights, the Vietnam era, and the tumult of the 1960s, his performances were central to then-contemporary ideas about where the American project was headed and what it was to become.

Implicit was a redefinition of socio-cultural attitudes central to the representation of Black Americans and championed by the likes of Martin Luther King, Malcolm X and Mohammed Ali. Though Poitier was not as prominently political as these figures, he was far from disinterested in the racially charged nature of the moment. Plus, he was able to capitalize on his fame by overcoming his apprenticeship in various Hollywood movies where he bubbled beneath the surface calm, often as a hoodlum.

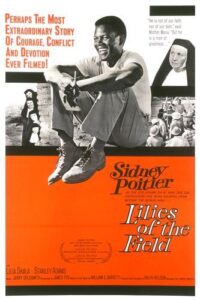

Following his Best Actor Oscar for Lilies of the Field, Poitier emerged in the mid-’60s as the pre-eminent mainstream personality for Black America that was most palatable to White American sensibilities and interests. In large part this was because of his courteous polish, handsome good lucks, subdued sexual charisma and overall skill as a screen personality without adequate precedent. Thus, Sidney Poitier was an original for times that required new cinematic images and situations to overturn years, if not centuries, of racist stereotypes.

Starring as Virgil Tibbs, Poitier holds together Norman Jewison’s film of John Ball’s novel that was subsequently translated for the screen by Stirling Silliphant. It opens to the strains of a theme song written by the movie’s composer Quincy Jones and sung by Ray Charles. Over the credits we learn that Tibbs is disembarking at a small-town railway station while a local policeman named Sam Wood (Warren Oates) performs his nightly rounds, including his peeping in on the home of a local tease.

When Woods finds a prominent businessman named Colbert slain in the wee morning hours, his boss, Sheriff Gillespie (Rod Steiger), appears at the crime scene to spearhead a speedy investigation. Tibbs is snatched up at the train station as much for a being Black as for being a stranger in town, and therein is the coincident spin upon which the movie works its timely sense of purpose.

After being told to confess to being a murder, Tibbs reveals he’s a vacationing homicide detective on his way home, and that he had nothing to do with Colbert’s untimely destruction. With disbelief Tibbs’s revelation hits Gillespie like a ton of breaks, not only for the way Tibbs comports himself but also after it becomes clear he is more capable of solving the crime than any member of Gillespie’s local law enforcement team. Unfortunately, Tibbs is also black and manages to focus the entrenched prejudice of the entire town upon him and Gillespie who is likewise an outsider only recently hired to bring order to local affairs.

Over a few days investigation, and despite Gillespie’s bumbling, Tibbs learns how Colbert was in conflict with the business interests of the local rich man named Endicott (Larry Gates). Using the inconsistencies of physical evidence and his own sense of things being out of order, Tibbs finally solves the crime as being one of accidental timing and much smaller stakes. In a bloody climax, it’s revealed that Colbert was killed by the town soda-jerk so he could pay for the abortion of his girlfriend, the local tease introduced in the film’s credit sequence.

Regardless of this Scooby Doo conclusion and its red herring-filled murder investigation, In the Heat of the Night is famous for its reluctant partnership as played by Poitier and Steiger. To film enthusiasts the movie is also well remembered for Jewison’s direction, Silliphant’s script, Jones’s score, Haskell Wexler’s cinematography and Hal Ashby’s Oscar-winning work as editor. But the lasting significance of the film is undoubtedly its representation of a Black man overcoming a number of White men.

This point, nowhere more significantly played out than in Tibbs’s confrontation with Endicott where they each slap the another, forms the new standard of how Black Americans could be represented on film. Tibbs is repeatedly demonstrated as the only competent police officer despite the clearly prejudicial behavior acted out against him. He is also the film’s moral center, and he acts through a professional mien that makes him uniquely capable of solving a murder that defies the rules of common sense. For all that, though, Tibbs is not the best part in the movie.

Steiger convincingly plays Sheriff Gillespie and shows the partial transformation of a racist cop into being a three-dimensional man with a conscience. In this way, Gillespie contributes to a pop art tradition of using Black characters and actors to instruct White characters and White people, generally, in the rules of humanity. And Steiger’s performance implicitly shows a troubled man—troubled by what I read as deeply closeted homosexuality—who is forced to recognize his many limitations while discovering how to keep control of himself and his small town.

As far as the Academy Awards were concerned, 1967 was defined by revolutionary flavors and one piece of old Hollywood escapism. Alongside the eventual Oscar winner, there was competition from Arthur Penn’s Warren Beatty vehicle Bonnie and Clyde that remains a cinematic classic. Mike Nichols presented Dustin Hoffman’s star turn in The Graduate, and Sidney Poitier doubled-up his role as the leading Black actor of his day in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner?(Stanley Kramer). Closing out these five nominated films was the musical Doctor Dolittle (Richard Fleischer).[1]

I’m not one to ignore the seminal importance of art acting within context to provoke cultural change. In the Heat of the Night is no doubt one such piece of art, and its legacy is closely tied to the way Virgil Tibbs stood up to “The Man.” Such a role would later contribute to Blaxploitation’s more oppositional tack, but in 1967 it was exactly the right moment for Tibbs to shock Gillespie out of his moral and ethical torpor.

As an overall assessment of the picture of the year, though, I’m hard pressed to agree with In the Heat of the Night being Best Picture. This is not to say that race and related questions of caste and class are secondary. But it is to say that aside from the Tibbs slap to Endicott’s deserving White face, and aside from those who argue for Jones’s score as one of the greats in movie history, In the Heat of the Night is relatively slight entertainment.

–August 31, 2020

[1] For more on the importance of 1967 in the history of movies, see Pictures at a Revolution: Five Movies and the Birth of the New Hollywood(2009) by Mark Harris