Imagine the pitch meeting: three men hunt a shark with a belly full of boy. Jaws!

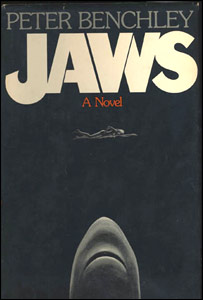

Peter Benchley was born into an upper-class family and the Ivy League. Upon graduating he became a journalist and contributed to various newspapers and magazines, National Geographic among them. With an affinity for the ocean, one of his assignments about sharks particularly appealed to him and provided the germ for his bestseller Jaws, the story of a great white shark that terrorizes a beach community.

Partly based on the Jersey Beach shark attacks of 1912, Benchley’s 1974 novel was an immediate literary phenomenon, earning him a pretty penny while lending him unusual authority among marine scientists. It also defined a formula he subsequently plugged-in to later novels like The Beast (1991) and White Shark (1994).

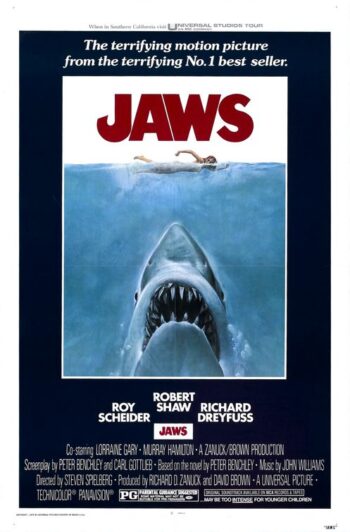

Almost immediately after the novel’s publication, movie producers David Brown and Richard D. Zanuck optioned Benchley’s book and secured the participation of wunderkind, Steven Spielberg, as director. Carl Gottlieb adapted the novel, and location scouts were dispatched to New England.

Shot on location in Martha’s Vineyard, which doubles for Amity, Long Island, Jaws is about a killer white shark that attacks swimmers during the summer tourist season. Police Chief Martin Brody (Roy Scheider) is saddled with protecting the locals and is simultaneously urged to keep the shark problem quiet to encourage tourism for the benefit of troubled local businesses. Needless to say, the shark makes meals of several sea goers until Brody assembles a crew to find and kill the rampaging animal.

Skippered by Quint (Shaw), with ichthyologist Matt Hooper (Richard Dreyfuss) to track and study the animal, Brody boards the Orca to confront the watery devil.

One by one, each of their schemes to trap the shark fails, and it begins to hunt them in open water. Eventually, Hooper descends into the depths in a shark-proof cage to poison the fish, but is presumed lost; the shark then kills Quint as it chews its way through the sinking Orca. Brody is finally the one to kill the shark when he explodes a scuba tank of compressed air in its mouth.

With a budget of $12 million, Jaws went on to earn $260 million in the United States and an additional $210 million abroad, becoming the definitive 1970s blockbuster that created a new standard for judging movies based on their commercial reach, confirmed as a profitable formula in 1977 with George Lucas’s Star Wars.

Significantly, the main strength of Jaws is its value as pure entertainment combined with a sharp societal commentary about life in a small seaside town. With an opening sequence of a skinny-dipping female swimmer being eaten by the rogue shark, including underwater footage of the big fish hunting, the movie cuts immediately into a whodunit like thriller about what killed the girl. As the attack impacts Brody’s community, his troubles multiply against the demands of keeping people safe, but also of keeping beaches open, otherwise the shark will choke the economic life out of Amity.

This sense of economic consequence, while based on Benchley’s novel, differs significantly in the way Gottlieb adapted the source to enable a satisfying movie. Where Benchley detailed Chief Brody’s plot line to include an adulterous wife, Gottlieb narrowed the back-story, making Brody a former NYPD officer and propping him up with a loving wife, Ellen (Lorraine Gary), and two sons, Michael (Chris Rebello) and Sean (Jay Mello). The novel’s class consciousness about the tourist economy were then projected onto the dollars-first mentality of Mayor Larry Vaughn (Murray Hamilton) who deliberately ignores the shark threat until it’s nearly too late. In addition, Hooper was made a sympathetic character rather than the boyfriend of Brody’s straying wife, thereby ensuring his affiliation with Brody so they might work together to kill the shark.

Altogether, Brody, Hooper, and Quint depict a three-man triangle, each point symbolizing differing aspects of manhood. Quint is the most obviously callous and vulgar aspect of traditional masculinity, at once action-oriented and demanding, yet also long experienced with the sea. Hooper is a new kind of man tempered by personal wealth, a formal education, and many worldly refinements while also being comfortable negotiating with the natural world to avoid bodily harm. Between them is Brody, the civilized man without the polish of a fine education or the trust of instinct.

Brody is the most complex character in the film and the source of our identification. Scared of the water and unable to swim, he is nonetheless tasked with protecting Amity, even though he’s been domesticated by wife and family, and does not wish to venture over the ocean on the Orca.

The three male leads also give Jaws its touch of humor and historical detail. For example, the famous USS Indianapolis sequence, in which the men retire to the ship’s mess to drink and tell jokes let Hooper and Quint exchange scars while Brody looks on, envious and uninvolved. Then Quint launches into his monologue about surviving the sinking of the Indianapolis in shark-infested waters during the closing days of World War II. Most of his cohort was eaten alive, and Robert Shaw uses his weather-beaten face to express deep sadness just as the shark starts to attack them.

Nominated for Best Picture of 1975 against One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (Miloš Forman), Barry Lyndon (Stanley Kubrick), Dog Day Afternoon (Sidney Lumet), and Nashville (Robert Altman), Jaws lost the top award but picked up three technical citations for Verna Fields’s editing, the film’s sound design, and John Williams’s score. This connection between Bruce the shark, so named by Spielberg in tribute to his lawyer, and the pulsing, manipulative score cemented a connection between John Williams and the high art of the movie soundtrack.

–September 30, 2020