“I wouldn’t have loved you if you were just like me.”

The French New Wave generally describes a late 1950s to early 1960s movement of young filmmakers who rebelled against the established industry. Because New Wavers grew up in the 1940s, exposed to new ideas about art and politics, post-World War II, they viewed movies as a personal form of expression connected with the unique voice of a writer-director, or auteur. This standard view is typically tied to the first features of Francois Truffaut (1932-1984) in The 400 Blows (1959) and Jean-Luc Godard (1930-now) in Breathless (1960).

Many film histories cover this summary and then point out the movement’s many influences that inspired filmmakers around the world. One problem with this story, though, is a preference for filmmakers who emerged from association with the journal Cahiers du cinema. Another complication is that the New Wave is a cult of personality, privileging filmmakers like Truffaut and Godard who became globally famous.

One final problem with the usual story of the French New Wave is that it is inherently sexist, as in the typical disregard for Agnès Varda (DOB 1928-now), a filmmaker still at work today whose contributions to movie history have only been recently elevated. Why? Because her early career was based in still photography, which informs her movies with a documentary-like pattern; because her focus tends to consider context rather than individual accomplishment; because she married filmmaker, Jacques Demy (1931-1990), whose work is often better known; because she became a mother.

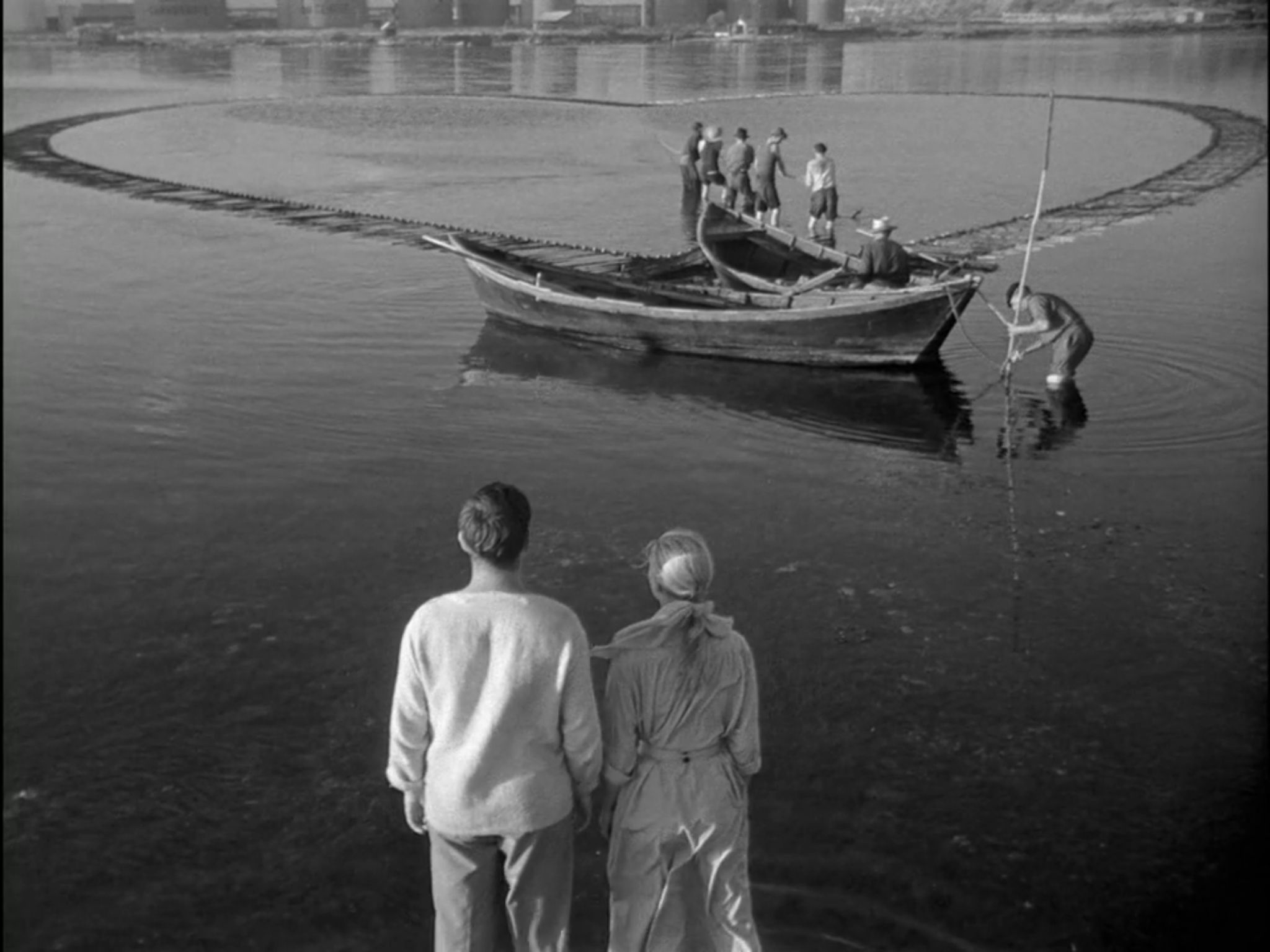

Given these blinders, the history of the French New Wave may really drill down to Varda’s first feature, La Pointe Courte (1955). It tells two stories: 1- a Parisian named Lui (Philippe Noiret) acts as tour guide through his home town, La Pointe Courte, as his wife, Elle (Silvia Monfort), confronts him with the fact that their marriage is crumbling. They walk around, talk, walk and talk some more, and finally resolve to return to Paris, together, now that the excitement of courtship has worn off in favor of friendship. 2- the villagers of La Pointe Courte, a coastal town, brace for sanctions against their traditional fishing habits that threatens their livelihood. At the same time the local people maintain communal ties through everyday work, leisure, argument, and life along the water.

Lui and Elle are naval-gazing, pretentious, Continental archetypes. In interviews Varda explained that this performance quality stems from how she directed Noiret and Monfort to avoid emotion and, in this way, they are photographic subjects rather than 3-D characters. Varda was then able to use them as geometric emblems. In one striking scene, the couple lament their First World problems while Lui faces the camera as Elle covers up half his face in profile. It’s a strange image, and it’s as artificial as an animated mouse.

The village story, in contrast, is warm and engrossing, tense from everyday tragedy (a little boy dies) and occasionally boring as a long day of waiting. Yet this quality of ripped-from-life rings true and makes La Pointe Courte an ethnographic portrait of a way of life that was then decades, perhaps even centuries old, right at the cusp of modern industrial farming and the homogenization of local communities in favor of corporate sameness.

Varda’s debut is a mixed experience for many viewers. But in its 86 minutes a great deal of balance is kept between addressing the new needs of urban young people like Lui and Elle and celebrating the traditions of old, old French village life in places like La Pointe Courte.

–October 31, 2018