“You don’t like her. My mother don’t like her. She’s a dog. And I’m a fat, ugly man. Well, all I know is I had a good time last night. I’m gonna have a good time tonight. If we have enough good times together, I’m gonna get down on my knees. I’m gonna beg that girl to marry me.”

In the early 1950s when television was new, a group of New York stage-influenced artisans and technicians worked to find solutions to the form of a flat screen medium with an unprecedented penetration into American living rooms. Broadcast standards of the time demanded broad material that would play well in urban and rural areas, alike, so there were variety shows and news programs, as well as comedies and hour-long dramas that showcased the stories of an ever-changing set of writers, some coming into their own with wildly creative ambitions.

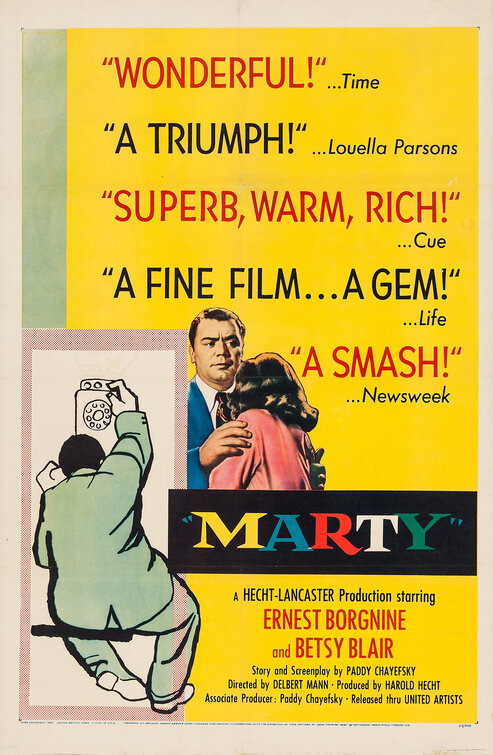

From such a fertile backdrop, the 1953 TV movie Marty, written by Paddy Chayefsky, was a bright shining moment in the first “Golden Age” of television. It tells the story of a homely butcher who is wasting away in terminal bachelorhood, and it’s a triumph because it describes ordinary people working through ordinary problems.

At the time, Chayefsky was lauded for his creative inspiration when much mass entertainment was, and still is, focused on beautiful people doing glamorous things. His teleplay was also widely seen as a self-reflexive project, for both Chayefsky and the show’s star, Rod Steiger, who thereafter became a celebrated movie and TV actor just as Chayefsky became an important American writer.

Following Marty’s original broadcast producer Harold Hecht, along with his silent partner Burt Lancaster, optioned the property and hired Chayefsky to adapt it for the big screen. Sequences that had been enclosed in a small, three-room studio for a live TV broadcast were blown out to accommodate several indoor and outdoor settings in the Bronx. The main characters and the thrust of the play, however, were left largely unchanged with whole lines of dialogue transplanted into the movie script. But the demands of feature filmmaking did require a few significant changes, such as Ernest Borgnine taking Steiger’s part, along with the addition of an optimistic pop song over the film’s closing credits.

Tagged with the line, “It’s the love story of an unsung hero!”, Delbert Mann’s Marty thrilled audiences in Europe where it first played well at the Cannes Film Festival and then opened domestically with a similar brand of expectant praise. The story’s fundamental sensitivity about awkward adults caught in the drab, repetitive ordinariness of their lives was striking to a post-War audience, many of whom were struggling with similar issues. Not insignificantly the film emphasized its ethnic, working class American milieu to play up the idea of an integrated and bustling world somehow passing by just outside of reach.

Borgnine worked against type where he was usually cast as a villainous heavy to instead portray a sensitive and big-hearted man. His depiction of Mary Pilletti is characterized by a pleasant grin and concern for the welfare of others along with a healthy appetite and subtly repressed control over his frustrations. Living with his mother, Mrs. Pilletti (Esther Minciotti), a classic Italian matriarch who lords over the last of her six children, and being the oldest and only unmarried of her offspring, their relationship is filled with affection and mutual concern.

Marty’s story centers on a Saturday evening out when he and his best friend, Angie (Joe Mantell), visit the Starlight Ballroom to dance and pick up girls. Neither man believes he’ll be successful, but Marty meets Clara Snyder (Betsy Blair), an on-the-nose definitive school marm, and they begin a gentle courtship that’s as sincere as it is unexpected.

Naturally, Angie is jealous of his best friend’s new girlfriend, Mrs. Pilletti becomes concerned about Marty’s changing fortunes, and Marty feels confused by budding romance. In the end, he calls Clara for a second date, much to the chagrin of his shocked friends, and in so doing he admonishes them for their tribal mentality when all any of them really want is to be in a happy, loving marriage.

“Just” a character study set over three days in the life of Marty Pilletti, Mann’s drama is a sociological study of adult neuroses about coupling and marriage. Though later times would call out these politics as awfully retrograde, particularly with the coming of age of the Baby Boomers, Marty sells the value of men and women joining together in marriage as the most natural thing in the world. To audiences of 1955 such an idea was quite conventional, but it’s in noting the crushing sadness of failing to achieve matrimonial satisfaction where Marty derives its emotional heft.

The way Marty both holds up and undercuts marriage as the end-all, be-all of success is both deeply troubling and oddly nostalgic. Troubling because it rests on the necessity of individual validation from an outside source; nostalgic because this supposition presumes a less complicated moral universe than the present.

How Marty went on to win the Academy Award for Best Picture in light of its relatively slight value, even when considering its timeliness and popularity, is anyone’s guess. Nominated as it was against Love is a Many Splendored Thing, Mister Roberts, Picnic and The Rose Tattoo, none of which are still considered among the best titles of 1955, Mann’s picture seems to have won its distinction through attrition. That is, it was the best of a limited group of nominees, even though there were five more remarkable films \ the Academy could have emphasized with citations and statuettes.

Heading the list is a pair of James Dean movies, Rebel Without a Cause (1955) and East of Eden (1955), which, along with Giant (1956) the next year, completed his screen legend due to his early death. Then there was Robert Mitchum’s tour de force in The Night of the Hunter (1955), Alfred Hitchcock’s enjoyable To Catch a Thief (1955), and the Spencer Tracy adventure-turned-social-problem-technology showcase in the CinemaScope Bad Day at Black Rock (1955), also featuring Borgnine in a supporting role, this time as a heavy and not the lead.

Any of these five films would have been a preferable Oscar winner to Marty. Still, the Academy pressed on with its paean to Lancaster’s production company, the value of the TV crossovers, and the importance of little films that win hearts with honest sentiment rather than a reliance on spectacle or superstars to set the screen on fire.

I accept Marty as a realist entertainment, and I agree there is an important place for this kind of film. It affirms ordinariness and the strength of the human struggle for happiness, and it manages to create tension with the situational conversation of three-dimensional characters.

What it isn’t, and what I think an Academy Award winning movie is supposed to be, is great.

–February 28, 2023