“Now, inside the black vault, there are three systems operating whenever the technician is out of the room. The first is sound-sensitive… The second system detects any increase in temperature… The third one is on the floor and is pressure-sensitive… Now, believe me when I tell you, gentlemen, all three systems are state-of-the-art.”

Popular action movies appeal to basic pleasure centers, favoring violence and excitement. The best popular action movies also extend the limits of what kinds of action can be produced because this one category of movies is where image-making technology always advance mind-blowing spectacle (Did I really just watch a tank race down a highway?). The corollary effect of this redefinition of the possible is exploring how fast the action happens before an audience is bored (terrible) or boggled (terrific).

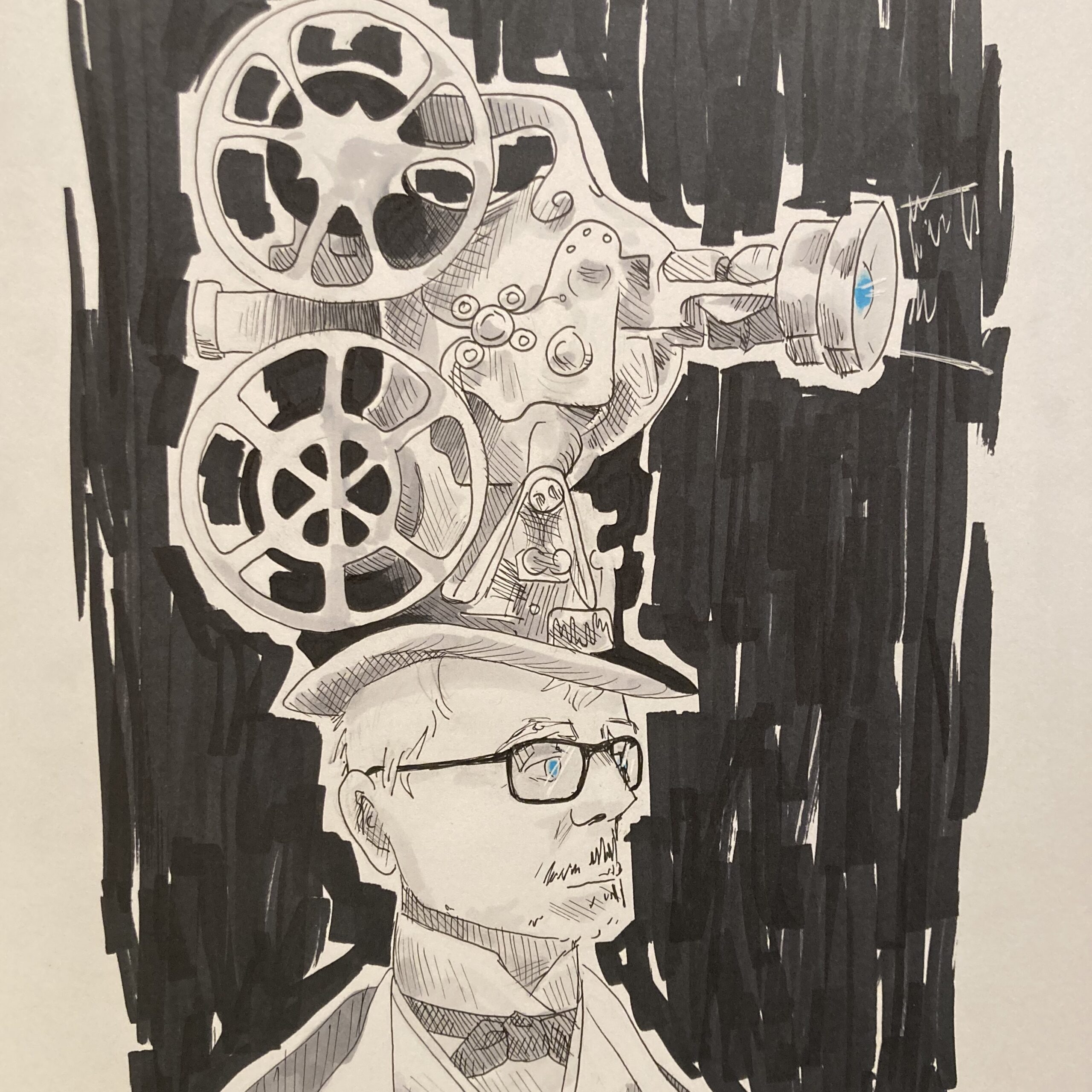

Brian De Palma’s Mission: Impossible (1996) was, in its time, an unequalled kinetic experience that proved-to-be a boggler. Moviegoers lined up in droves to watch the titular impossibility come true, and they did so because the movie was fast, furious, and marvelously escapist, eventually outpacing the cultural touchstone of its source in a 1960s TV show, and spawning, as of this writing, five sequels.

To watch Mission: Impossible, now, is to notice how far along moviemaking technology has progressed since 1996, and how quickly we require fast action, or we fall asleep. The movie is really a kitsch object organized around a series of stunts we collectively regard as “sweet” because younger folks have forgotten, or don’t care about, this movie’s original glory in moving beautiful people through space on a caper.

The story orbits Ethan Hunt (Tom Cruise), a dexterous and handsome Impossible Missions Force (IMF) operative. Hunt works for Jim Phelps (Jon Voight) and the team they lead becomes involved in a complicated plot to undermine deep cover CIA operations. After a set of ambushes that kills off most of Hunt’s team, he goes rogue to prove that he’s a patriot. Thereon he teams up with two new technicians, Luther (Ving Rhames) and Krieger (Jean Reno), plays a bait and switch game with a dangerous arms dealer, Max (Vanessa Redgrave), and tries to convince his smarmy boss, Kittridge (Henry Czerny), that he’s 100% A-Okay, and not a super-agent capable of breaking into CIA headquarters, which he does, on-screen, in one of three set pieces that mark the story’s three act structure.

Cruise is at his hammiest. Apple corporation dots the product placement landscape. Everyone works with then-cutting-edge computing technology that doesn’t compare with the slowest smart phone. The plot is needlessly complex and filled with Cold War conventions that involve heavily accented, English-speaking Eastern Europeans attempting to overwhelm good boys and girls.

The thing is, Cruise works to earn our appreciation of the risks he will take as an actor, and the incredible stunts Hunt will attempt, because his goal is maximum entertainment value. Seen alongside today’s movies, the special effects are dated, and the choreography should be sped up because modern moviegoers digest on-screen action far faster than in 1996. Yet the overall impact of Mission: Impossible is textbook, on-the-nose linear storytelling that accelerates through a ludicrous plot to throw Cruise/Hunt into situations he shouldn’t survive, but does, because he’s performing a mission: impossible.

–October 31, 2018