“So give me a stage / Where this bull here can rage / And though I could fight / I’d much rather recite / That’s entertainment.“

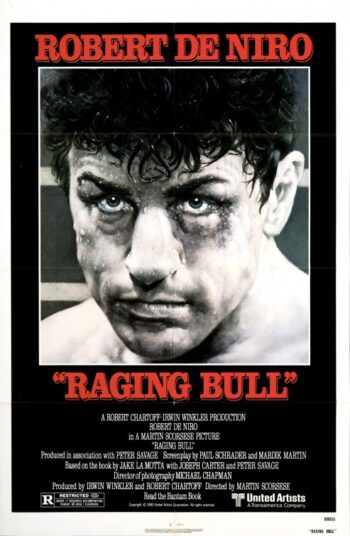

The reputation of Raging Bull, Martin Scorsese’s masterpiece from 1980, is hard to oversell or adequately describe. Critics from around the world regularly claim the movie’s status atop “best of” polls of global cinema, and many filmmakers describe it as an early inspiration, even as a permission slip, to explore unique methods and styles of filmmaking. But Raging Bull is a hard, hard movie to watch, and an even harder movie to like, although it’s clearly a work of art that is rightfully recognized for being something special.

As a biopic, the movie is adapted from the autobiography of champion boxer Jack LaMotta, which was published in 1970 as Raging Bull: My Story. Written for the screen by Paul Schrader and Mardik Martin, the movie’s story focuses on the 23-year period in LaMotta’s life from 1941-1964 when he emerges as a 19-year old title contender through the time when he’s a has-been-turned-nightclub entertainer. This narrative is bookended by two dressing room sequences in 1964 when Jake prepares to take the stage and perform his act while the rest of the movie runs in chronological order, spinning vignettes that trace the destructive path of our hero who never once ceases being an unpleasant, dangerous cad.

These vignettes include many sequences in the high- and lowlights of LaMotta’s boxing career, and there are several really tense domestic scenes as we watch LaMotta’s private life unwind. Key supporting players include Joe Pesci as Joey LaMotta, Jake’s brother and trainer, and Cathy Moriarty as Vickie LaMotta, Jake’s second wife. These two role players help define the ethnic White American post-War backdrop, as well as provide the scaffold for Italian American stories ever since, and they temporarily prop up the lead performer, Robert De Niro, until the role he’s submerged himself into demands that all subordinate payers exit stage right.

Much has been said about De Niro’s performance in this movie. Stories of his obsessive exercise regimen to cut weight and train in the pattern of a world class middleweight boxer, in his middle 30s, and then turnaround to gain 60 pounds in the same year through an equally obsessive regimen of overeating to seem like the mess of a man that same razor sharp boxer would one-day become, have set the stage for method performers ever since.[1] The thing is, De Niro is utterly convincing, totally enraged, scary, repulsive, and oddly vulnerable; in short, he’s a big baby with deadly weapons hanging from his wrists.

De Niro’s LaMotta beats up people and gets beaten up, over and over again. The black and white cinematography of Michael Chapmen, frequently shot through canted angles, unusually vicious close-up, and in slow motion, renders the human-scale brutality of Jake’s lifestyle and profession something gorgeous and breathtaking. We watch as Thelma Schoonmaker’s editorial choices shift between flying jabs and cracked noses to crowd inserts and chomped cigars, all of it designed as a ballet celebrating peak-condition bodies being cut to pieces, literally as a constructed set of cinematic tours de force, and figuratively as mid-century boxing carves out its gladiatorial niche.

Images stick out everywhere, whether in blood dripping from a ringside rope to the subway floor tile pattern in a Bronx tenement apartment. Raging Bull breathes-in the historical period it recreates, and it never once flinches from a key fact of De Niro’s performance: we don’t know why Jake is the way he is, and we never get the impression that he will ever reform or improve himself. His story is about a monstrous force of jealousy and violence that’s contained in one man who offers no pop-psychological profile we can cling to that will excuse his behavior. Instead, we see a sociopath incapable of even modest self-control, save for the discipline necessary to give or receive physical punishment.

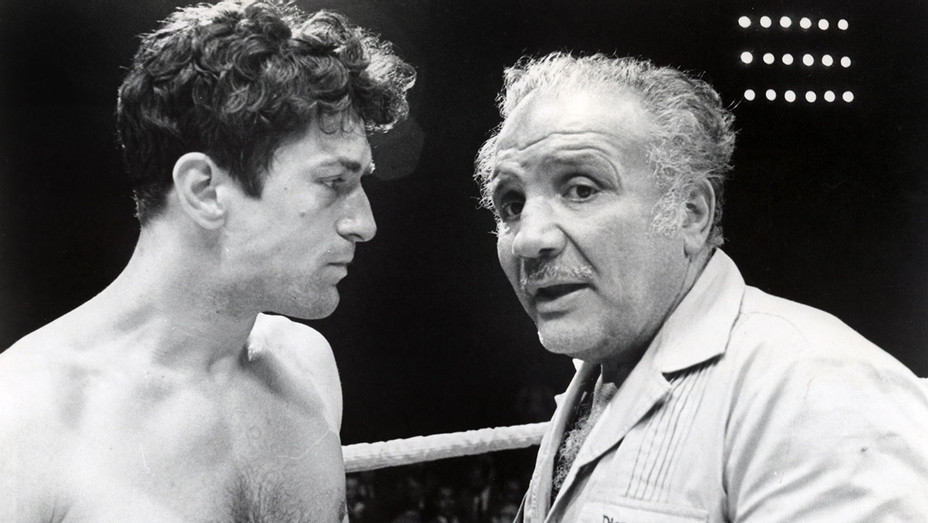

The thing I can’t get over is that Jake LaMotta, then in his late 50s and more than two decades removed from professional boxing, served as a creative consultant for Scorsese’s movie. Production stills are available through google, in which images of champion quality young LaMotta vies for the eye with gray-haired old LaMotta instructing De Niro-as-LaMotta on how to play himself. The contrast in this quick course through historical imagery is shocking, no more so than in the fact that Raging Bull is no valentine to an aging idol.

Like the source autobiography, Scorsese’s movie sets out to describe the folksy mythology behind “The Bronx Bull,” as LaMotta was sometimes credited, but it is absolutely clear about his personal investment in violence. De Niro’s Jake, like the actual man who whispered in the ears of the cast and crew throughout active production, is a wife beater, a domestic terrorist, and a funnel for self-punishment in the ring where his credo reduces to, “I did it my way and no one every knocked me down.”

LaMotta, the movie character, metes out and absorbs incredible punishment, often at the tail end of a long boxing match, because he thinks the sport ought to be decided by pure physical dominance rather than a point tally in subjective round-by-round scoring. Even knowing this fact about himself, and also knowing about the role that organized crime played in tilting the betting line to put short-money contenders in the ring with designated champions, means nothing to Jake who stubbornly beats his way to the top, including beating through the bodies of his wife and brother, when necessary.

In one of the movie’s oddest, most unpleasant moments, it’s 1958 and Jake leaves the nightclub where his comic set bombed only to see Joey emerge from a grocery store. Jake follows his brother into a parking garage, kissing and hugging Joey, who is clearly overwhelmed and disgusted. The moment won’t end, and in Jake’s awkward affection we see the underbelly of a lonely man without a network to stand on.

Another unpleasant sequence sets up the sibling hostility. It’s 1950 and Jake is one year into his reign as world middleweight champion, but he can’t stop festering about whether Vickie is faithful. While setting up a new TV, he needles Joey about whether Joey is having sex with Vickie, so Joey leaves and Jake attacks Vickie. Then, in a kind of obverse of the Norman Rockwellian ideal of wholesome American values, Jake enters Joey’s home, striding down the hallway as Joey and his family eat dinner, peppering each other with insults and threats. Then Jake pummels Joey, also hitting Vickie who has trailed him into her in-law’s home, while Joey’s children stand by, absorbing this terrible lesson about how violence erases the human quality of everyone it touches.

–October 31, 2019

[1] See Robert De Niro, again, in Cape Fear (Martin Scorsese, 1991); Charlize Theron in Monster (Patty Jenkins, 2003); Christian Bale in The Machinist(Brad Anderson, 2004), Batman Begins (Christopher Nolan, 2005), or The Fighter (David O. Russell, 2010); Natalie Portman in Black Swan (Darren Aronofsky, 2010); or Joaquin Phoenix in Joker (Todd Phillips, 2019), for just a few notable examples.