“Listen, that’s the attitude of too many morons in this country. They think these hoodlums are some sort of demigods.”

Al Pacino’s scene-chewing turn as Tony Montana in Brian De Palma’s Scarface (1983) is a mess of a good time. There’s a whole lot of snorted blow and bulging eyeballs, and the dreamy, post-disco face of Miami remains strangely alluring, particularly when encountered on late night cable TV.

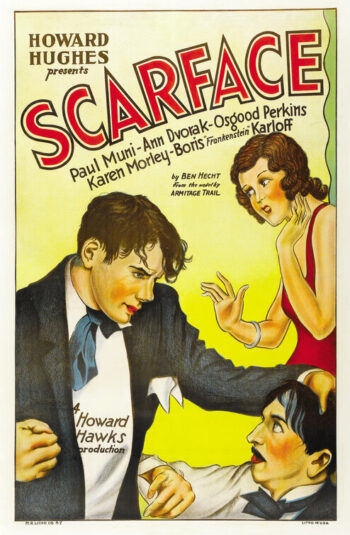

But Pacino’s version is not the version of the titular character. For that version, the learned turn to Howard Hawks’s 1932 pic Scarface, sub-titled The Shame of a Nation consequent to review by the Will Hays-dominated Motion Pictures Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA), a precursor to the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) that now gives movies the G-through-NC-17 stamp of approval.

The older Scarface is set in Chicago in the 1920s. So, even as an old movie (to us), Scarface was already a period piece of a by-gone era, Prohibition, loosely organized around the biography of Al Capone.

The story opens with hitman Tony Camonte (Paul Muni) killing his boss’s boss, whereupon he fills the resulting power vacuum with increasing acts of violence until he is finally killed by the authorities. Along the way he starts a war with a rival “family” and can’t seem to stop from being his own worst enemy.

Tony has a best friend, Guino (George Raft), who loves Tony’s sister, Cesca (Ann Dvorak), on whom Tony has incestuous designs. Tony also has many recognizable traits of the social climber who seeks to legitimize his criminal past with a respectable civic future, which is complicated by a gaggle of reporters, a super didactic big city publisher, lots of tough-guy cops, and several memorable supporting performers, including Boris Karloff, who had become an icon the year before as the monster in James Whale’s Frankenstein (1931).

The reason to see Scarface today isn’t just for authentically appreciating the Pacino re-make. As an early Sound era movie, Scarface is still capable of shocking viewers with on-screen events that would be outlawed from 1934 onward when the Hays Code began enforcing restrictions for on-screen violence, sensuality, and morality, partly in response to the success of this movie.

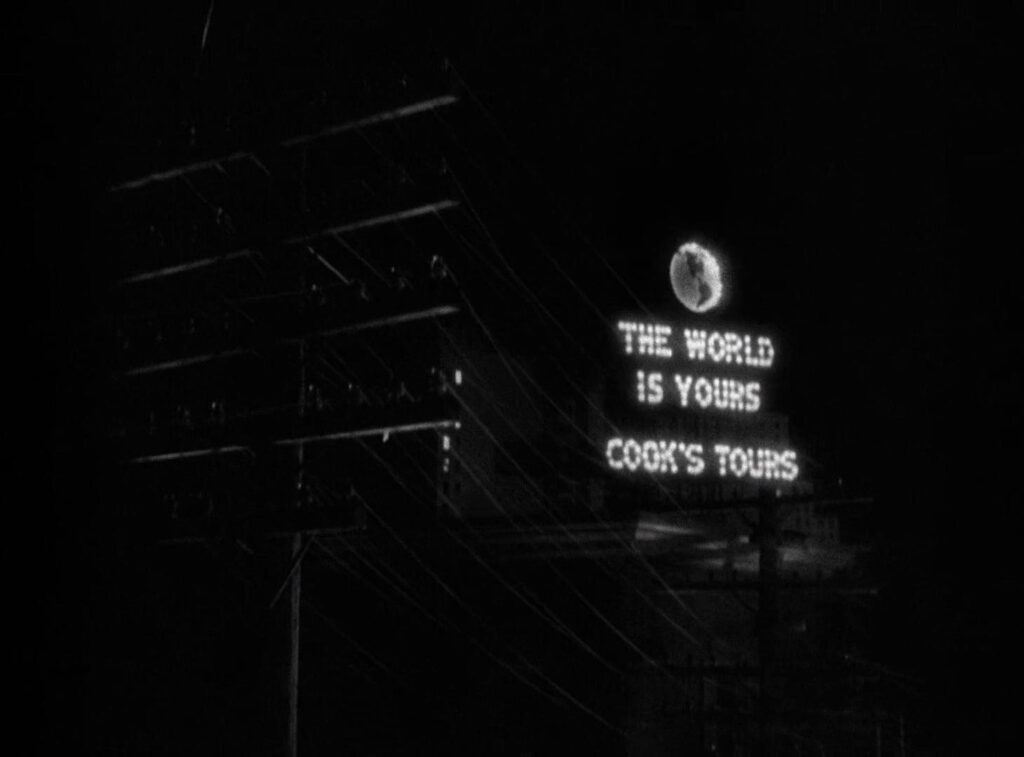

For instance: Scarface features multiple Tommy-gun-fed drive-by killings, naked sexual innuendo, lots of beer distribution, which was still illegal in 1932, and the critical perversion of Tony’s character since he loves, and I mean loves, his sister. We can see the foundation of today’s many on-screen car chases in one terrifically charming high-speed stunt sequence, and we can clearly see that Tony is the most interesting person in the story world.

As a landmark gangster film, Scarface is also an interesting portrait of American capitalism. Where any market economy works to fill wants and needs with products and services in pursuit of profit, a gangster like Tony simply expands the list of available products and services to include the likes of bootleg liquor and prostitution. In this way, Tony and his ilk are nothing more or less than entrepreneurs trying to make a buck.

As an Italian immigrant, Tony is further characterized by his lack of social standing (he’s an ethnic “Other”) and low cultural capital (he speaks accented English badly). He’s physically scarred with a crucifix-shaped scar on his cheek (that’s on-the-nose Italian Catholicism) and he wears his riches ostentatiously in a series of ugly suits and commented-on design choices that fill his apartment home with bric-a-brac. Despite these excesses, alternately played for laughs and painful asides, Tony clearly wants to achieve distinction and protect his family while living up to a code that has little respect for arbitrary laws. Bending to the ethical and moral landscape of Hollywood in the early 1930s, Scarfacefrequently interrupts Tony’s story to ensure that we, the audience, recognize how awful he is, ultimately punishing his acts of rebellion through a machine gun execution to conclude the movie.

–September 30, 2018