“I got clean in prison. And I’ve been out for 4 days.”

According to Hollywood rumor Susan Sarandon once said that no woman can out-perform her own exposed bosom. It’s axiomatic; the attraction of movies is based on seeing things normally obscured from view, so the revelation of a naked body is often overwhelming.

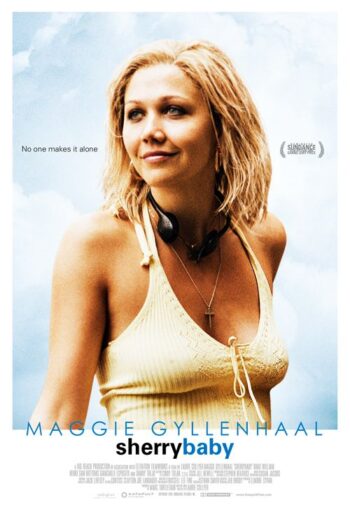

There are any number of female entertainers who complicate the pleasures of staring at a woman’s body. This effort can take the form of transformation from trophy-woman into spectacle (Madonna), destabilized expectation from nice girl into someone powerful (Julia Roberts), and unvarnished character study. Enter Sherrybaby (2006), written and directed by a then-very-pregnant Laurie Collyer, starring Maggie Gyllenhaal.

The movie traces parolee Sherry Swanson (Gyllenhaal) as she moves into a halfway house, two and half years sober from getting clean in prison, unable to figure out the next step in life. She’s in her mid-20s and has no job skills, save for sex work and petty burglary, although she has learned to care for children in the prison’s childcare system, and she wants to be reunited with her daughter. It’s not a promising portrait; in short order things go wrong.

The movie’s strength is conveying a specific circumstance. Being formerly incarcerated, Sherry finds herself in a world dominated by male predators, each of whom wants their pound of flesh to facilitate the next stage of her fall from ground level into the ditch.

Gyllenhaal offers a raw performance. She showcases Sherry’s pathology in full; we see how drug addiction leads to sex work leads to thievery leads to prison and an unconvincing come-to-God conversion to get through the next obstacle. Each of Sherry’s problems results in Gyllenhaal disrobing, overwhelming her very layered performance with a clear view of her mostly naked body, and this much nudity marks Sherry as a thing to be stared at by the men who control her, as directed by a woman (Collyer), in order to ultimately reveal (SPOILER ALERT) the root of her trouble in a molester-father who began abusing Sherry in girlhood.

It’s a kitchen-sink realist kind of movie dominated by waiting for the other shoe to drop. Will Sherry live up to her parole agreement? Will her brother be an awful person as he cares for Sherry’s daughter? Will Sherry OD?

In all ways the movie is ambiguous. It ends without a parent-child lovefest or death in a flophouse. Sherry simply drives away from her daughter, who is safe, knowing that she must make her rehab appointment and then maybe things really will get better.

–October 31, 2018