“Three days from anywhere. A Lone Prospector.”

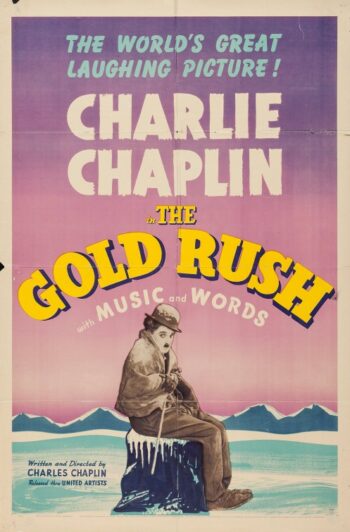

Charlie Chaplin’s The Gold Rush (1925) is a sweet confection from an earlier time before sound film. Built on vignettes, The Gold Rush follows a poor simpleton, The Tramp (Chaplin), who tries prospecting during the Klondike Gold Rush of 1898.

When The Tramp makes his way through a snowstorm, he finds a lonely cabin occupied by Big Jim (Mark Swain). The pair have an uneasy relationship, soon complicated by the arrival of a criminal, Black Larsen (Tom Murray). The trio run out of food, whereupon Larsen leaves the cabin seeking help, Big Jim loses his mind, and The Tramp wanders into town where he first sees the beautiful Georgia (Georgia Hale). Smitten, he tries to woo her away from a roughneck named Jack (Malcolm Waite) but sees his hopes ruined. Then Big Jim returns, willing to share his gold stake for help securing it. Newly wealthy, The Tramp learns how Georgia has begun to care for him, and they begin their life together. The End.

Where modern movies spend time motivating a lead character with psychology, obligation, or appetite, Chaplin’s Tramp is splendidly narrow in conception. He craves friendship and romantic love, and he’s perplexed by cynicism and cruelty. Poor as he is, he’s willing to share everything in his possession, and he’s perfectly able to see the glass half empty. He’s kind in a world that often isn’t, and he acts without calculation, perfectly at ease with the vagaries of chance, willing to adapt to ever-changing circumstances.

Having been firmly established in the minds of moviegoers from 1914 onward, The Tramp is topped by a bowler hat that he wears over baggy trousers and a tight suit coat. He’s an everyman character with too-large shoes and an out-turned step who sports a thin mustache, eventually called Hitler-esque, and he carries a flexible cane, the genteel affectation of a man who knows his manners and exhibits great courtesy in mixed company.

Something remarkable about The Gold Rush is the way it turns toward comedic bits and gives them ample time to develop. In one memorable scene, we watch The Tramp make a meal of his boot; the laces become noodles and the hobnails become bones to suck clean of leather meat. In another scene, a fantasy of how The Tramp wishes Georgia would see him, he forks dinner rolls and “dances” with breaded feet on a tabletop.

For decades, these moments have amused moviegoers. There are no explosions or profanity, just invention and heart. Watching The Gold Rush we delight in physical humor, feats of derring-do, in-camera effects, and genuine pathos. In his desire to find warmth and companionship The Tramp proves himself to be a model for everyone, and we glimpse part of the soul of Charles Spencer Chaplin, a boy born from abject poverty who became one of the world’s most enduring icons of joy.

–October 31, 2018