“We’re going this way.”

I like a movie where I see a man’s penis. Call it reflexive homoeroticism, but I interpret the gesture as an affront to standard taste, and I like it. When we see William Petersen’s penis in William Friedkin’s To Live and Die in L.A. (1985), it is the most necessary equipment imaginable in the scene where it appears, as well as a sign of the movie’s overall schizophrenia.

To Live and Die in L.A. is about a United States Secret Service agent named Richard Chance (Petersen) who is obsessed with capturing a counterfeiter named Rick Masters (Willem Dafoe). Chance’s method involves cruelty, violence, and the abuse of his new partner, John Vukovich (John Pankow), who survives both Chance and Masters in the movie’s conclusion.

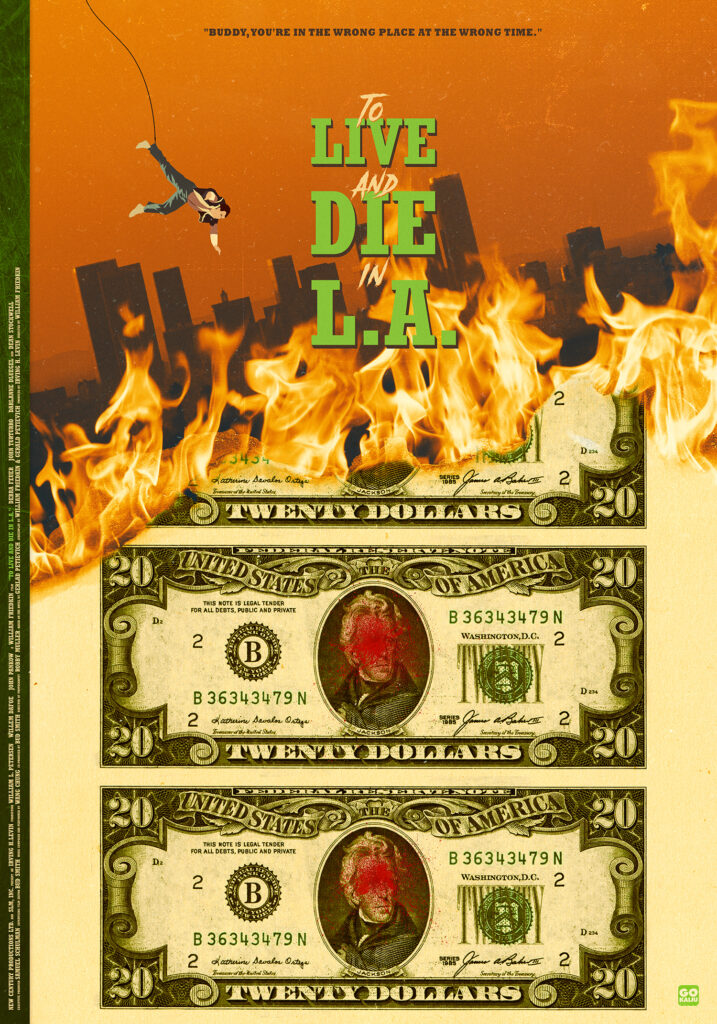

A modestly profitable movie, To Live and Die in L.A. is remembered for a car chase that develops to one side of Chance’s effort to bring down Masters. But a thrilling car chase it is, rolling over rail lines near Union Station, through the flood channels that Danny Zuko raced in Grease (Randall Kleiser, 1978), across the loading docks of San Pedro, and finally up a one-way off-ramp that concludes with a jackknifed semi-trailer crushing cars to a standstill.

The chase is a show piece of careful sound manipulation (garbled dialogue and grunts bridged by screeching car sounds and whiplash speed) and stunt-based performance. A typical cut moves from a closeup on Vukovich, to a mid-shot of Chance and Vukovich from the hood of the car—the windshield missing for a clearer image—to a reverse shot from Vukovich’s seat in the back of the car aimed into oncoming traffic, to a cutaway detail, to the bad guys in pursuit, and back to a mid-shot from the hood while Chance swings the steering wheel.

It’s just terrific, but it’s also so much nonsense. There is no good reason for the sequence to exist, save Friedkin’s reputation as an action filmmaker that allowed editor M. Scott Smith plenty of room to make something from nothing. But exist this car chase does, and it remains, all these years later, crackerjack work, from start to finish.

The whole movie has this quality of brilliance and drift. For a little while we watch the secret service protect President Reagan from an Islamic terrorist. Then we learn how Masters makes fake $20 bills. Then we visit a strip joint, a federal prison, a South Central basketball court, the dressing rooms of a dance troupe, and we briefly visit Chance’s ludicrous beachfront condo on stilts. It’s all surface and no depth, just a stream of hard knock one-liners scored to a soundtrack by English rockers Wang Chung. This wall-to-wall combination of synthetic music, stylized imagery, and constant posing, as in, “This is cool,” is damnable, but, in isolated moments, works way better than it ought to despite being so giddily bad and in bad taste.

But about that penis. To Live and Die in L.A. is the story of appetites, whether for sexual gratification, excitement, or wealth. Metaphorically, the whole movie is an undirected phallus, assaulting us in our darkened theatrical privacy, offering blunt-force violence (several people are shot, point-blank, with shotguns) to paper over the cracks of a story that is always artificial and unmotivated.

As genre entertainment, it’s often called a neo-noir. If it were a building material, it would be plastic.

–November 30, 2019