“You gotta control your smiles and cries, because that’s all you have and nobody can take that away from you.”

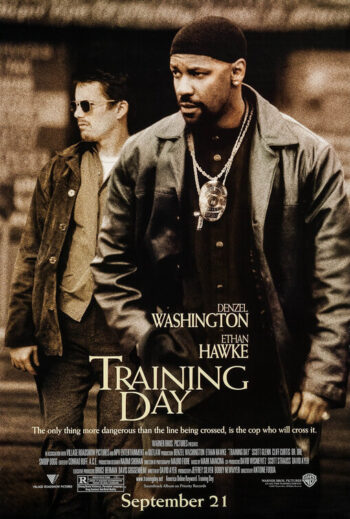

Antoine Fuqua’s Training Day (2001) is Denzel Washington’s Best Actor Oscar audition tape, but it’s really the story of a White boy who can’t stray from championing corny old-fashioned virtues like honesty and justice.

Jake Hoyt (Ethan Hawke), a 20-something Valley Boy, wakes up early one morning so he can try out for an undercover narcotics unit. He’s got a newborn daughter, a dependent wife, a home in the ’burbs, 18 months on the job as a uniformed cop, and he’s a former high school football star, a strong safety, where his job was and is to provide the last defense against anything.

Jake joins Alonzo Harris (Washington) for a training day, offering himself as raw material. “I’ll do anything,” he says, and Alonzo appraises him patiently, taking stock of Jake’s moral core wrapped in naked ambition.

It’s this level of surveillance, of seeing and watching, of understanding what needs to be acted on or ignored, that makes Training Day go. Shot in a big fat rectangle with lots of horizontal motion, the whole movie is a clinic on looking through obstacles—windshields, security doors, racist assumptions—to find significance in little things like the occasional metaphor. “To protect the sheep you gotta catch the wolf, and it takes a wolf to catch a wolf,” Alonzo tells Jake, and we get his point.

Jake quickly succumbs to Alonzo World logic, and we realize, ahead of Jake (ah, dramatic irony) that Alonzo has recruited him as a scapegoat for a crime that Alonzo must either atone for or he’ll be killed by Russian mobsters. The sequence of dares that Jake then suffers include: smoking PCP-laced marijuana; breaking up a drug deal with college kids; harassing a low level drug dealer (Snoop Dog); stealing money from another drug dealer via the stash house of the drug lord’s girlfriend (Macy Gray); killing an even higher level drug dealer (Scott Glen), an ex-cop and Alonzo’s one-time trainer; meeting with the crustiest and most cynical of LAPD leadership; playing cuckold to Alonzo’s assignation with his girlfriend, Sara (Eva Mendes); and, finally, standing up to his new “boss.”

Jake takes three beatings across the story, but he enjoys the karma of seeing how his do-gooder habit yields a get out of jail free card that saves his life in a bit of narrative convenience that features Clifton Curtis and Raymond Cruz. Alonzo is not so lucky; he gets machine gunned by the Russkies, as if this were a pre-Code gangster movie, and we close on Jake as he returns home after the worst first day of a new job ever.

Training Day debuted at the Venice Film Festival nine days before the 9/11 attacks and then it was released, stateside, on October 5, 2001. Audiences generally enjoyed it, although not enough to make it profitable, and critics applauded Fuqua as an emerging Black filmmaker while also celebrating the moral fortitude of David Ayer’s script that reversed the Hollywood convention where an elder White man is good while his younger Black sidekick is bad. Here, Alonzo is the worst of the worst because he’s more vicious, better dressed, faster-thinking, more persuasive, angrier, hornier, smarter, and more thoughtful than his fellow players, but he is, in the end, little more than a Black criminal who exists to put street cred on a White boy, Jake, who will surpass him, no matter Alonzo’s bluster about, “King Kong ain’t got shit on me.”

–March 31, 2019