“I have wrestled with an alligator. I done tussled with a whale. I done handcuffed lightning, thrown thunder in jail.”

Long before he was an ad man for an electric grill, George Forman hit hard. In Leon Gast’s When We Were Kings (1996) we see this power expressed through archival footage of the young Foreman training with a heavy bag anchored to the floor by one of his trainers. In punch after punch he dents the bag while we listen to journalists describe his legendary strength in no uncertain terms: the guy is a tall Black bruiser.

Muhammad Ali is lighter-skinned and funny. We hear his rhetorical powers in various interviews, press briefings, and training sequences in which we hear him conjure ear worms that entangle the thoughts of his admirers, detractors, and opponents. He’s a natural performer whose vocational skill allowed him to elevate pugilism into the aesthetic plane of dance.

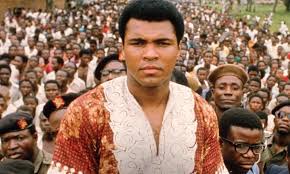

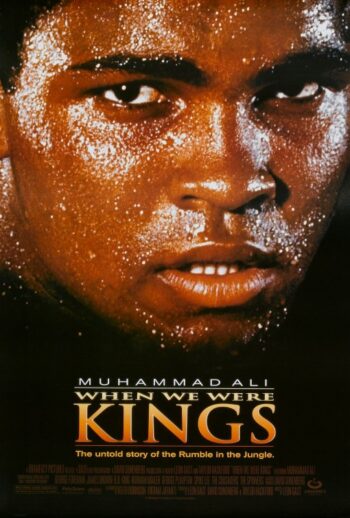

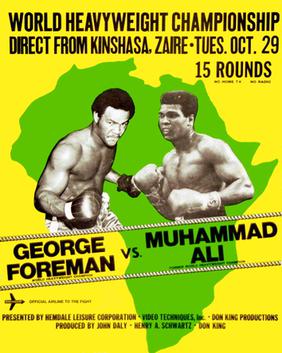

Gast’s documentary is hero worship at its finest. Straddling the line between hagiography and persuasion, When We Were Kings recounts the story of the “Rumble in the Jungle,” the heavyweight boxing match between world champion George Foreman and the former champ, Muhammad Ali, staged on October 30, 1974 in Kinshasa, Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo) in front of a live audience of 60,000 and to a worldwide broadcast audience that numbered into the hundreds of millions.

Originally organized by Don King as a boxing match with a $10 million purse, the match was meant to cap a multi-day arts and music festival. When Foreman sustained a split eyebrow while training, which delayed the fight for six weeks, the “Rumble in the Jungle” grew well past being a showcase of President Mobutu’s ethnically cleansed, post-colonial state of Zaire and into a media circus.

On one side of the equation was Ali, a charismatic activist, eager to be the center of attention. On the other side of the ring was Foreman, a quiet athlete who was perfectly willing to box and box hard.

Gast’s documentary forms around the two men and their months of preparation that led up to the “Rope-a-dope” strategy Ali used to beat Foreman, i.e. wear the big guy out and knock him down. But the strength of the doc is its temporal design that shifts from the testimony of expert storytellers like George Plympton and Norman Mailer from the mid-1990s, to musical performances by B.B. King and James Brown during the Kinshasa arts festival, to newsreel and archival material from Ali’s past, all delivered Ken Burns style with zooms on still photographs and busy montage sequences. We are convinced of the world-historic importance of this one athletic event that broadened the scope of what Black manhood might be in the mid-1970s, and we are retrospectively aware of the cultural importance of Ali, now deceased.

Yes, that portrait is tied to the Black Buck stereotype. Yes, Foreman becomes a caricatured no-nothing with the silver lining that he subsequently changed the direction of his life through the present. In the end, though, Gast’s story broadens from being “just” another sports doc-reconstruction to become a celebration of Ali who is celebrated as being uniquely capable of living through the dual role of cultural hero and mortal man who would eventually, after decades of struggle, succumb to complications of Parkinson’s disease.

–November 30, 2018