“The story of bird migration is the story of promise – a promise to return.”

It’s difficult to overstate the scale of the natural world. This planet is big; the oceans cover most of the world’s surface area; we are but a speck among teaming millions of living species, competing with one another for water and sunshine. Few of us can truly conceive of the size and mass and power of all things beneath our feet and above our heads; Earth is a landscape of totality for all of humankind.

Still, many documentarians have spent whole careers building stories that bring this immensity to life, usually through miniaturization, by focusing on one species in one place at one time, perhaps only a season or two. The success of these storytelling efforts is stunning. We can watch meerkats or lions, penguins or soldier ants, and the stories we apply to these species to express how they live and why, exerting themselves in something like a natural habitat, conform to narratives of struggle, exhaustion, and triumph.

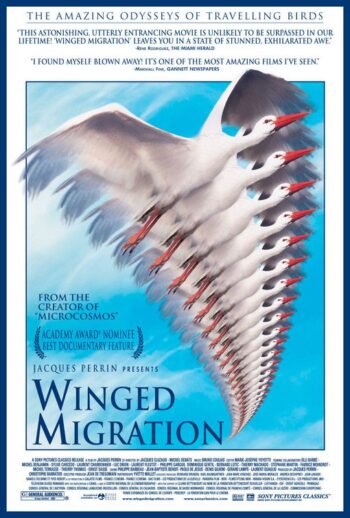

Into this fantasy land of reality-based stories stepped a crew of filmmakers led by the Frenchman Jacques Perrin. Working closely with his co-directors, Jacques Cluzad and Michel Debats, it was the latter 1990s when newer cameras were coming on-line, making far away objects observable and very small, fast-moving things suddenly clear. The documentarians tapped resources, including governments, NGOs, and established wildlife experts, to better focus their collective lenses and find a way to dramatize, to inspire, people to care about birds.

Their resulting 2001 movie, Winged Migration, is the layered presentation of dozens of species of migratory birds, moving over landscapes on all seven continents, which took three years and many millions of dollars to produce. Every nature documentary trope is herein present: movement across hostile and beautiful territory; predators hunting prey; mating dances that lead to a new generation; death; renewal; the change of seasons; and the occasional, but ever-present, influence of our kind, manipulating the face of nature and changing the pre-existing pattern of Earth.

Winged Migration also brings something extra to the fold: intimate videography that flies alongside the migrating birds, sometimes at a distance, it seems, of inches. The resulting images are stunning. We see plumage and beak detail, the shape of talons and tail feathers, the left-overs of hearty meals, dilating pupils. And we fly, how we fly, alongside Canadian geese, as just one example, beating wingtips in the undulating piston of movement that carries these birds thousands of miles to and from breeding grounds.

By now the technology of moving pictures has advanced a great deal since the early Aughts. Many of us carry in our pockets near-4K-capable cameras embedded in our phones, and motion stabilizing gimbals are cheap. But to see Winged Migration isn’t just to watch an old landmark documentary that we should gaze upon and call “sweet” because it was, then, the limit of image making technology alongside the natural world. Winged Migration is equally a summation of nature-based AV programming that has since been mainlined into whole cable and satellite TV networks and streaming content, making our screened view of Earth every day, common, and numbingly plain. At the same time, no current documentarian can do much more than note how man-made influence is corrupting the cycles and age-old pattern that Winged Migration brings to life, and for which a certain kind of viewer may wonder, “how was that sequence shot?,” but finding no adequate answer for the instinct of birds.

–April 30, 2019