“Life marched at double-quick in those feverish days of ’17.”

It’s hard to consider artifacts from an earlier time. Not only is there a need to establish context, there is an equal need to evaluate what’s discovered on its own merits as well as in regard to the present.

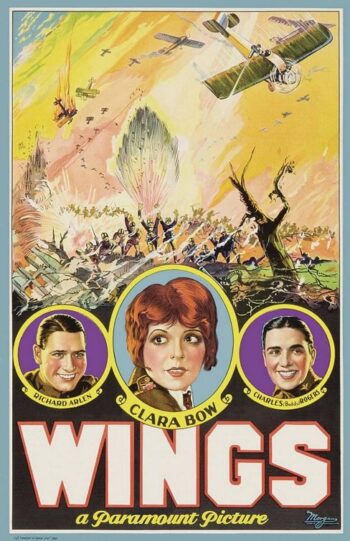

Tagged as, “The Drama of the Skies,” Wings was, for many years, a signature piece of movie special effects and a high point in the production of war films. It was also the first and only silent movie to win the Academy Award, and this distinction is important.

With the proliferation of synch sound movies in the late 1920s, virtually every silent film was made a relic to times gone by in a mere season, or two, of technical upgrades to cameras and theater spaces. Likewise, there was a turning away from the non-naturalistic form of silent film acting and screen direction involving stylized performance, which supercharged a new standard to evaluate on-screen excellence.

Looking at Wings with an original score recorded from the console of a Wurlitzer Pipe Organ, I was forced to reflect on these differing standards between then and now. I felt disappointment in the film’s attempts at physical comedy, largely through the supporting character Schwimpf (El Brendel). I was also reminded of the need for audience literacy and the accompanying attention subtitles require. Plus, I enjoyed watching the ’20s “It” girl, Clara Bow, do her darnedest, just like it’s fun to see Gary Cooper in a cameo role as ill-fated Cadet White long before he became a superstar.

As an interpretive treat I observed how Wings is sprinkled with odd moments that break the seamless storytelling technique and expose certain of its cultural assumptions. For example, ethnic English speakers are portrayed on-screen with costume choices and casting decisions, and they are reinforced with title dialogue using slang and punctuation to suggest non-standard English. These titles also become tools for manipulating mood since the dialogue and explanatory material is written over illustrations that comment on the story world action.

While recognizing how Wings is one of the most famous silent films ever produced, we must also acknowledge it as not one of the best.

Though its plot concerns two American flyboys enlisting to fight in World War I, the story is actually centered on two competing love stories. The first involves Jack (Charles Rogers), the film’s lead, and his neighbor Mary (Bow) who secretly loves him. Unfortunately for her, Jack loves an urbane young woman named Sylvia (Jobyna Ralston), although she loves David (Richard Arlen), Jack’s deepest rival. When Jack and David go off to flight school, they form a quick friendship in the air war over France and their romantic dual subsides. During the climactic battle featuring a fit of mistaken identity, David gets killed and Jack returns home as a war hero to finally accept Mary’s devotion after working Sylvia out of his system.

Nominated for the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences very first awards banquet, Wings was singled out for its achievement among four now realtively-obscure titles, The Last Command, The Racket, Seventh Heaven and The Way of All Flesh. Were it not for being the first Oscar winner, even before the term “Oscar” was coined, Wings might very well have been all-but-forgotten, too.

This is not to say the film is without merit. It originated certain scenes, images, and characters that have been absorbed into the vocabulary of war movies. Now easily dismissible because of our ever-advancing digital reproduction techniques and more sophisticated use of miniatures, the film’s flying sequences were then-considered state of the art, and they remain a thrilling accomplishment in the trade of stunt photography.

Since I am disappointed by the film despite these strengths, I am also able to see how Wings suffers from the same tendency that dogs many films, then and now. Running over two-hours with a simple story, three lead actors, and only a few plot problems to work out, Wings is far too long.

Because MGM sponsored and organized the Academy and because Paramount Pictures produced Wings, it now seems generous that Wings won top honors. Of course, Louis B. Mayer’s home studio, MGM, would recoup Paramount’s win in the next few years with wins of its own for The Broadway Melody (Harry Beaumont) in 1929, Grand Hotel (Edmund Goulding) in 1932, Mutiny on the Bounty (Frank Lloyd) in 1935, The Great Ziegfeld (Robert Z. Leonard) in 1936 and Gone with the Wind (Victor Fleming) in 1939, yet it’s significant that a rival studio was given first movie of the year honors ahead of the parent organization. Retrospectively, we might term this a gentleman’s agreement among entertainment oligarchs working hard to consolidate a very sensitive, and sometimes quite lucrative, new-ish industry.

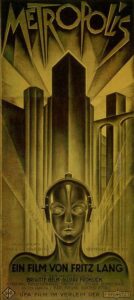

Another note of consideration concerns the Academy’s nationalistic impulse. With the passage of time, the expansion of film production across the world eroded this level of America first-ness. In the first year of the Academy Awards ceremony, though, such open mindedness went missing and important work was ignored, as was the case for Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927), in every way a greater cultural loadstone that continues to encourage fans based on its own merits.

Is it still worth taking a look at Wings?

For the purist, yes, but for everyone else, it’s a regression to earlier times that may not be worth the two-hour search for quality entertainment.

–December 31, 2017