“As near as I can see, the only thing you can take with you is the love of your friends.“

Frank Capra is the epitome of New Deal-era Hollywood. A longtime Columbia Pictures contract employee, his movies are built upon the harsh material realities of the times but equally buoyed with a mixture of optimism, ingenuity, and intelligence that is the hallmark of his heroes and heroines. Each of his films is therefore filled with reminders of passing bad times and upcoming good ones, and these stories end up as part of the sentimental carapace surrounding the Hollywood myth itself.

Informed by a nostalgic sense of simpler times, the traditional values of Capra’s films are drawn from frontier myths. Men are honest, trustworthy, and heart spoken, even when working under duress or experiencing the worst from their fellow man. Likewise, women are demure, excitable, and pleasant in order to act as the true north in a typically amoral universe. Minority groups are also present, though usually to one side of plot developments, while his stories continuously affirm the importance of seeking truth, the central value of family, and the sense of being on God’s right hand.

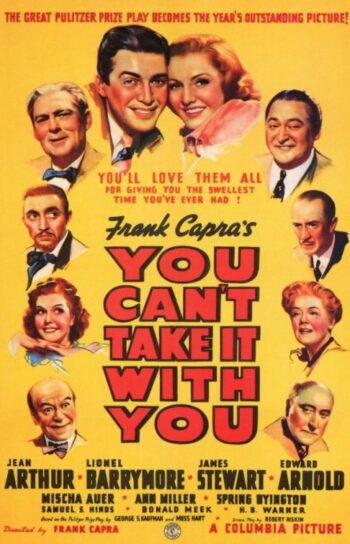

Adapted by Robert Riskin from a play by George S. Kaufman and Moss Hart, You Can’t Take It With You is a movie perched uncomfortably between the worst of the Depression’s height and the terror of a coming World War. As such, it’s an imprint of an idyl, 1938, while also being another in a long line of Capra movies dealing with the specifically American personality and its various flaws and foibles.

Opening on Wall Street, Anthony Kirby (Edward Arnold) is a determined banker with little time for anything save his next transaction. Into his hierarchical world interrupts Kirby’s son, Tony (James Stewart), vice president in the family business, who brings with him an important complication; namely, a private landowner won’t sell his home to build a new munitions factory.

With indifference to the struggles of little people standing in his way as faceless names in the way of advancing capital, Kirby dispatches his minions to bend the landowner to his will. Little does he know that Tony is in love with a company employee, a young woman named Alice (Jean Arthur), granddaughter of the thorny landowner affectionately known as Grandpa Sycamore (Lionel Barrymore).

Moving then in two different but increasingly related directions, the movie concerns two forms of reconciliation. On the one hand, Tony and Alice seek family approval for pending nuptials. Meanwhile, Kirby continues to try bulldozing Grandpa to reap another windfall that will surely add to his riches while further corrupting his sense of goodness in the world.

Naturally, Tony and Alice are perfectly matched, yet his parents remain indifferent to her bohemian sensibility as an affront to their social standing. Conversely, Grandpa and his unusual household of family and friends believe in pursuing what makes them individually happy, and they view Tony’s parents as the opposite of what’s most important in the world. Though the Sycamores are presented as weirdos, they are also the more clearly nurturing and loving household with members that include a playwright, fireworks manufacturer, marimba player, stamp assessor, and two Black servants.

As Grandpa continues to resist the sale of his home, Kirby’s lieutenants expand their efforts to intimidate him. Simultaneously, Tony takes Alice’s invitation to host their families for dinner but shows up with his parents one night too early to throw both groups into disarray. Plodding to an unpleasant conclusion the evening is ended with a police bust, indirectly instigated by Kirby, that finds everyone arrested for disturbing the peace.

While awaiting arraignment, Grandpa explains to Kirby how the pursuit of happiness is more important than making money and predicts that the banker will end up a failed man. Kirby scoffs at the idea, although the prospect weighs heavily in his mind through the ensuing press attacks that result in Alice dishing out just desserts to her would-be in-laws before storming off for parts unknown without Tony.

Attempting to make everyone happy, Grandpa sells his house because he wants the Sycamores to join Alice on her journey away from heartbreak. Poised to bring off his deal that will be the biggest feather in his bonnet, ever, Kirby has a crisis of conscience after he learns that Tony is leaving Wall Street to find Alice and make himself happy because he really loves her and knows that banking life isn’t for him.

Befitting the Capra-esque, de rigeur happy ending, Kirby sells Grandpa’s house back to him and gives his ascent to Tony and Alice’s union. As they pray together for health, happiness, and the good Lord’s influence, Grandpa welcomes the Kirby clan to a Sycamore family dinner as everyone grins at one another about an optimistic future.

Based as it is in the title phrase, “you can’t take it with you,” the moral lesson about pursuing personal satisfaction over material gains is everywhere evident. To one side of this imperative are a number of important-to-consider, throwaway points about ideology, social and class distinctions, and the virtues of everyday people.

You Can’t Take It With You flirts with notions about patriotism, self-confidence, hard work, and loyalty as the true basis of personal success, thereby idealizing American capitalism as a primarily social structure allowing people to bind themselves to one another as the preferred method for overcoming mutual troubles, just then easily remembered as the Great Depression. Using recent historical memory of mid-1930s life, Capra’s movie is motivated by nearly propagandistic goals that encourage mutuality rooted to a strong sense of individuality that must, by necessity, be watered down lest it turn into an insurmountable obstacle for social cohesion.

Not striking too hard at the point, You Can’t Take It With You presents a group of likable misfits who would be gutter-bound and destitute were it not for Grandpa Sycamore and his sanctuary-like house. Instead of complicating these vibrant fantasies about personal expression with material considerations, Capra dismisses the need for earning money and conforming to society on the way to perfectly expressed individuality.

It’s a tough distinction, this idea of forming supportive communities and remaining idiosyncratic and unique. Almost like a hair style worn when its moment is done, the sentiments of You Can’t Take It With You seem somehow out of touch with the historical shift into war just then beginning to sweep America and the rest of the world, a time when individual identity was yoked, by martial purpose, to the defense of the wider nation acting in a hostile world.

Though I see the importance of the film’s message, including an early star turn by Jimmy Stewart, it’s actually quite a slow entertainment and it’s not very affecting. It’s also oddly out of touch with itself since its characters are nonconforming except for their conformity (to each his or her own until someone needs the group’s strength) and unique save for their sameness (eccentricity is great but let’s all worship the ties of family). All lessons about what’s most valuable distill to notions of family and togetherness even while the film’s families and opportunities for togetherness, most notably when the Kirbys and Sycamores are locked up by the police, result in further frustration and dissatisfaction before eventual release and redemption.

The 1938 Academy Awards race had a relatively high number of truly important works nominated for Outstanding Production. You Can’t Take It With You won the top award, but it was in competition with nine other titles, five of which are now minor notes to history, Test Pilot (Victor Fleming, 1938), Four Daughters (Michael Curtiz, 1938), Pygmalion(Anthony Asquith and Leslie Howard, 1938), The Citadel (King Vidor, 1938), and Alexander’s Ragtime Band (Henry King, 1938), although the same can’t be said about the other four nominees.

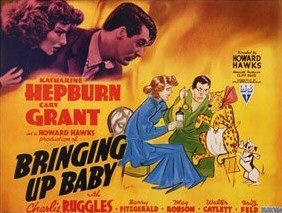

Among them, perhaps the most famous is The Adventures of Robin Hood (Michael Curtiz and William Keighley, 1938), Errol Flynn’s swashbuckling follow-up to Captain Blood (Michael Curtiz, 1935). But there was also Bette Davis in Jezebel (William Wyler, 1938), Spencer Tracy in Boys Town (Norman Taurog, 1938) and that most memorable of all period dramas, Grand Illusion (Jean Renoir, 1937). Plus, it bears mention that Bringing Up Baby (Howard Hawks, 1938) wasn’t even nominated, despite being the arguable highpoint of screwball comedy and one of the early high points in the notable, and lengthy, careers of both Katherine Hepburn and Cary Grant.

Such a strong cohort of Oscar nominees highlight certain negative judgments about You Can’t Take It With You. The first is a tip of the metaphorical hat to Capra whose work has informed the memories of at least two generations of Americans, now mostly deceased, like both of my sets of grandparents who would have seen themselves in this story. To them, You Can’t Take It With You can’t be discounted for possessing sentimentality that no longer works for modern audiences. Then there’s a second, and perhaps more demanding, point about timeliness as concerns the merits of particular films.

Context sensitivity aside, You Can’t Take It With You isn’t a great movie, although it is a museum exhibit of a hinge-point in modern history. I recognize how it impacted its original audience to express a desirable fantasy for making a better world that never came true, exactly, but that doesn’t mean a person can re-watch it today for much satisfaction.

–December 31, 2017