I’ve been reading about movies for decades, dating back to my first encounter with magazines like Starlog. In so doing, I’ve learned the stylistic leanings of my time, and of times past, and I’ve come to appreciate the fun of mulling over opinions not my own.

The reason I continue reading about movies is that I recognize how movie-going is often solitary; I watch movies on a screen, whether it’s an iPhone 5s up through IMAX, but mostly I watch movies alone. Learning what others think is a way to connect myself with like-interested people and better accept the normalcy of my desires.

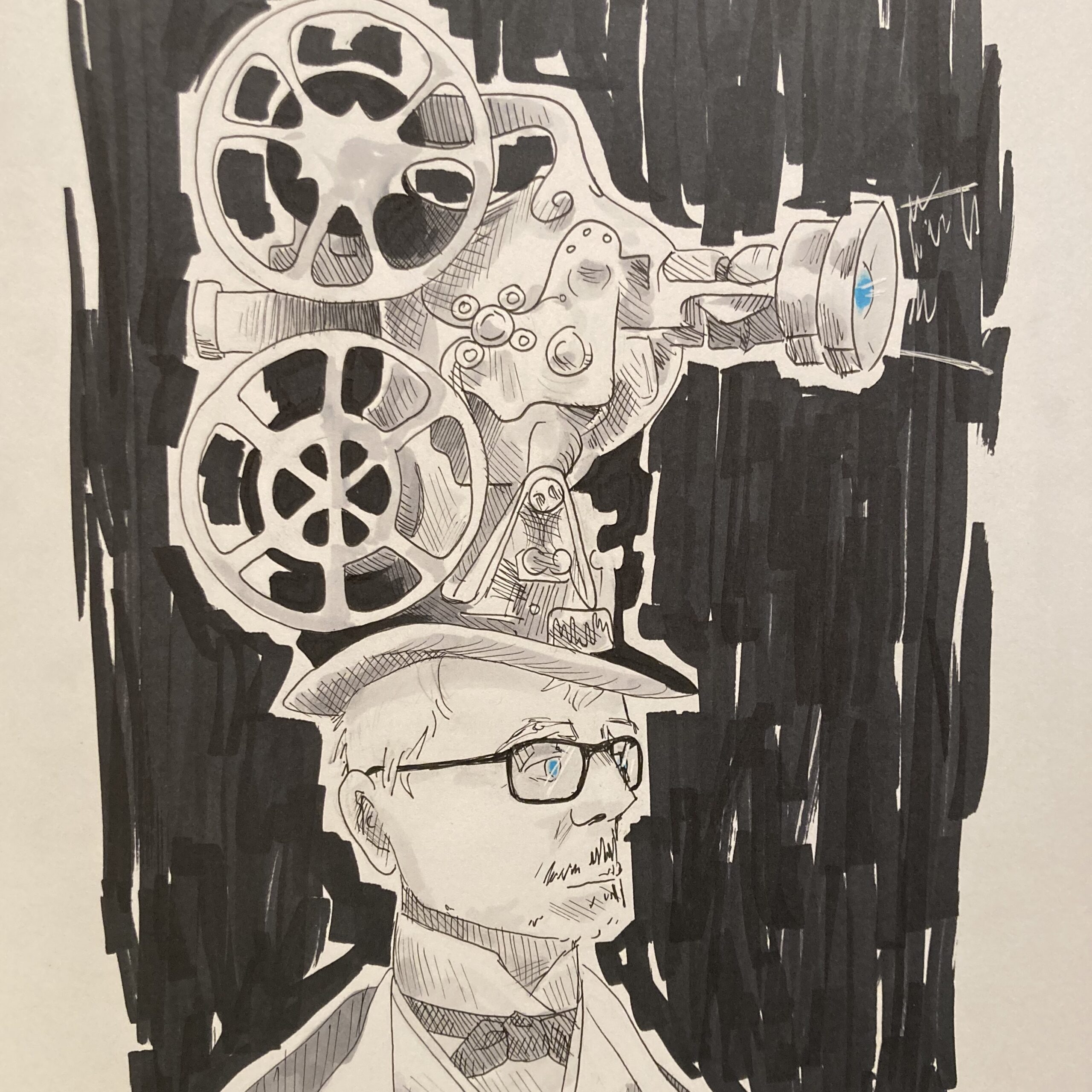

Among movie-writers certain names crop up as influential: Pauline Kael, say, or Joe Bob Briggs. One still-living éminence grise cut from the cloth of fandom rather than the academy is David Thomson, a British-born writer and occasional educator who has produced more than a dozen books, including A Biographical Dictionary of Film (first edition in 1975), and How to Watch a Movie (2015), my present concern, which was a disappointment, truly.

The book’s self-description fills out the opening chapter: “There are situations in our lives where the way we watch the world may be necessary for the continuation of life. How to Watch a Movie is a guide to studying film, and having more fun and being more moved. But watching is a defining part of citizenship, a bearing witness” (page 9).

More than 200 pages later Thomson returns to his purpose in the conclusion: “You came into this book under deceptive promises (mine) and false hopes (yours). You believed we might make decisive progress in the matter of how to watch a movie. So be it, but this was a ruse to make you look at life. The true subject of movie is seeing and being seen…” (page 226).

Did you notice a slippage from intention through execution?

I stumbled onto the book in my local library, thinking: “Great. I teach movies. How does David Thomson do it? What can he offer me that will make me a better movie-goer?”

The answer is, in short, not much.

While Thomson does have writerly flare, his organizational capabilities are all over the place. His chapter headings imply, or tease out, contents of interest, such as “Alone Together?”, but the ensuing essays present ideas that may hold up in the liveness of conversation, or even in a lecture or v-log, but they do not convincingly build persuasive arguments on the page.

Thomson is extremely learned in the history of movies with a reach that spans from the present (he has extended remarks on the 2014 Denzel Washington vehicle The Equalizer, directed by Antoine Fuqua) back through the early history of the medium (L’arrivée d’un train en gare de La Ciotat by Auguste and Louis Lumière, from 1896, features prominently). And he’s prepared to engage with the expanding idea of what movies are in an age of memes, streams, and distracted screen experiences.

For this reader, someone seeking new insights from a well-established master and taste maker, How to Watch a Movie is mostly the transcript of a famous dude getting away with it.

–September 30, 2018